In 2024, nearly 4,000 individuals in Belgium opted for euthanasia, reflecting a significant increase from the previous year. Advocates of this legislation champion it as a paradigm of compassion and personal autonomy. However, critics caution against a growing desensitisation to death and a subtle decline in the quality of care. Caught in the middle are patients, families, and doctors, navigating not only grief and pain but also an increasingly medical and routine process.

On 13 February 2015, Christiane, an 80-year-old woman, prepared herself for a momentous occasion. Her two daughters were present, the family doctor had been notified, and in the diary beside her bed, she had written the date along with the words: Le grand jour ("The big day").

Christiane had been diagnosed with a rare form of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also referred to as motor neurone disease (MND). As her ability to speak, swallow and breathe deteriorated, her physical condition was failing; nevertheless, she had one final prerogative in Belgium: the legal right to decide the timing of her demise.

In 2002, Belgium became the second country globally to legalise euthanasia, following the Netherlands. Since its enactment, Belgium's euthanasia law has been characterised as one of the most liberal and contentious in the world. This legislation permits medical professionals to administer life-ending medication to patients who are enduring "unbearable" physical or psychological suffering resulting from a serious and incurable illness.

In 2024, 3,991 euthanasia cases were officially recorded, marking a 16.6% increase from the previous year. Consequently, euthanasia now represents 3.6% of all deaths in Belgium. The majority of patients are over the age of 70, with 54% diagnosed with cancer and 26.8% suffering from chronic multi-pathologies. Cases attributed to psychological suffering accounted for 1.4%.

The majority of euthanasia procedures occur at home (50.4%) or in hospitals (30.2%), including 6.3% taking place in palliative care units. Notably, only one case in 2024 involved a minor, a provision that has been permitted since a controversial amendment to the law was introduced in 2014. This development brings the total number of cases involving minors to six over the past decade.

The rise in euthanasia cases has prompted both concern and support within the community. For some individuals, such as Catherine Rombouts – Christiane's daughter – euthanasia is viewed as a compassionate and personal choice. Conversely, it raises concerns regarding the evolving boundaries between care and control for others.

A daughter's perspective

"She did not wish to be a burden," reflected Catherine Rombouts. "She had always valued her independence and dignity. This choice was entirely consistent with her character."

Christiane, Catherine Rombouts' mother.

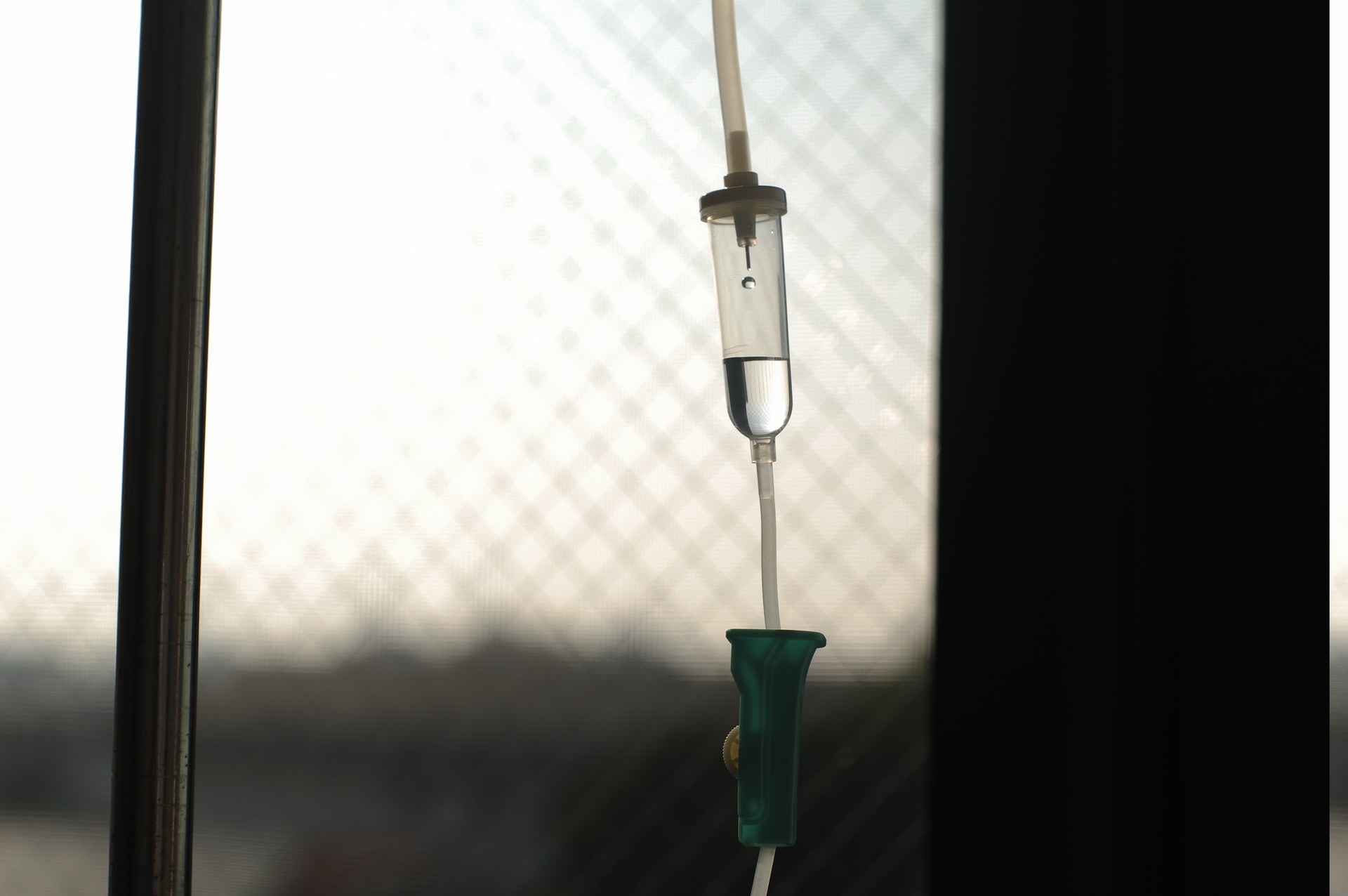

Christiane passed away peacefully in the presence of her loved ones following a brief medical procedure. A physician inserted a catheter and administered a barbiturate (thiopental), resulting in her passing within minutes. "She did not suffer," Rombouts stated. "There was no fear or panic. It was a serene departure. It was exactly as she had desired."

This experience prompted Rombouts to co-author Le grand jour, a photographic book documenting her mother's final days, collaborating with historian Sophie Richelle. Beyond serving as a personal tribute, the book has emerged as a significant testimony regarding how Belgian families experience and commemorate euthanasia.

"What is often absent from public discourse is the perspective of those who accompany an individual through the process of euthanasia," Rombouts remarked. "This narrative encompasses not only our mother's story; it is also fundamentally ours."

'The Big Day' by Catherine Rombouts

The changing social script of dying

Historically, the experience of dying was a prolonged and communal event in which families gathered and shared care collectively. The process of death was often marked by uncertainty and gradual progression. However, with the introduction of euthanasia, this experience became characterised by a bureaucratic formality, defined by a predetermined date, time, and plan, thereby altering the traditional understanding of the dying process.

This transition fundamentally alters the role of caregivers as they accompany individuals in their final moments. When death is scheduled, caregivers must adjust both emotionally and practically.

"The ten days between choosing the date and the act itself were complicated: suddenly, there was a countdown. And that countdown was difficult. Because several times, she called me saying she wanted it to be over," Catherine added.

The ambiguity associated with not knowing when death will occur has traditionally been integral to end-of-life care. Whereas, in the context of euthanasia, caregivers now prepare for farewells with clinical precision.

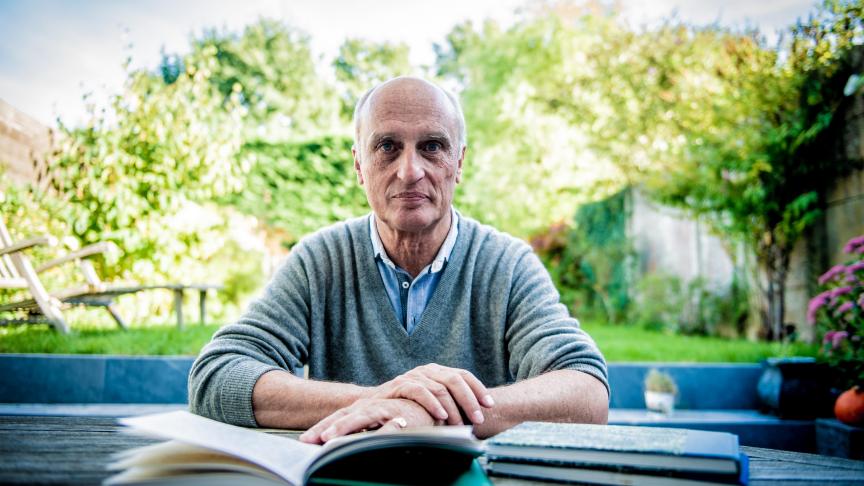

Dr Yves De Locht, a Brussels-based physician, has performed dozens of euthanasia procedures since 2008. He admitted that it took him "years before daring to perform [his] first euthanasia." His very first patient, he recalls, was a Catholic priest. "He told me: 'my health is one thing, my beliefs are another,'" De Locht said.

"He was in pain. He wanted to die with dignity. It's the most emotionally difficult thing I do as a doctor. But also, perhaps, the most meaningful. When I leave the room, I often feel I’ve helped someone escape a suffering no one else could relieve," he added.

Yves de Locht has been performing euthanasia procedures in Belgium for 15 years. He now shares his testimony in a book published in France. Credit: Mathieu Golinvaux

A recent report by MCC Brussels, a conservative think tank, however, presents a dissenting perspective on euthanasia, suggesting that this practice may not enhance patient autonomy as proponents claim. Instead, it raises concerns regarding the potential expansion of state and medical authority over matters of life and death.

The report critiques the increasing "bureaucratisation of death" and the prevalence of vague terminology such as "death with dignity." It posits that the legalisation of euthanasia has resulted in undue pressure on vulnerable patient populations, blurred ethical distinctions, and a growing desensitisation of the intrinsic value of human life.

The report highlights developments in Canada, where one in 20 deaths are attributed to euthanasia. This figure rises to one in 14 in Quebec. While Belgium's statistics are comparatively lower, its regulations are more permissive, encompassing psychiatric patients, individuals with disabilities, and minors under specific circumstances.

De Locht, an advocate for euthanasia, acknowledges these broadened criteria but asserts that the evaluative process in Belgium is both rigorous and transparent. "I do not make decisions in isolation," De Locht stated, emphasising the requirement for second or even third opinions. A detailed ten-page report is submitted to the federal commission after each case.

Nonetheless, he acknowledges the prevailing concerns associated with the issue. "The law protects both the patient and the physician; however, it undeniably imposes substantial responsibility."

Belgium is currently experiencing an influx of requests, including many from international patients, particularly those from France. "We can refuse requests, as we operate under a conscience clause. Nevertheless, the pressure is mounting," he states. "At times, patients do not meet the legal criteria, and there are instances where we lack sufficient resources."

Related News

- Euthanasia or assisted suicide: Where is the EU heading?

- Nearly 4,000 people opted for euthanasia in Belgium in 2024

- Assisted dying: What's the law in Belgium?

The report also scrutinises the European Union's initiatives to standardise euthanasia policies, cautioning that strategic litigation, lobbying, and cross-border activism might compromise national sovereignty. This perspective reflects increasing apprehension among conservative groups. De Locht asserts that Belgium's safeguards are robust and that abuse occurrences are rare. The law also prevents clandestine euthanasia, a practice that continues to exist in France (3,000 cases each year, according to De Locht).

"The determination to discontinue life-prolonging treatment is distinct from euthanasia," Frawley articulated. "Declining care is not synonymous with the active termination of life."

However, these discussions often seem abstract for families such as the Rombouts family. "My mother made her choice," she states. "She confronted death with courage, and we were fortunate to reside in a country where she could exercise her autonomy." The controversy surrounding euthanasia arises from its engagement with universal themes: the fear of suffering, the weight of loss, and the inquiry into what constitutes a dignified death.

"This is not primarily about ending life," De Locht notes. "Rather, it is about alleviating pain in the most humane manner possible, for the patient, and for the caregivers."