On Friday, citizens of the Czech Republic will head to the polls to vote for their next prime minister against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic and the release of the Pandora Papers, which give damning evidence of corruption by the incumbent Andrej Babiš.

But even before investigative reporting revealed that Babiš purchased a €19.5 million dollar chateau in France using shell companies to hide his identity, accusations of corruption were being lodged by his opponents.

One of those opponents is Ivan Bartoš.

In coalition with Mayors and Independets, he’s also polling at 27.5 percent, not that far behind the 31.1 percent majority held by Babiš, especially when you consider that his party only claimed 0.8 percent of the vote in 2010.

Bartoš is a Pirate, and “during these past years, they had quite a lot of success in local elections,” Vladka Musalkova, Director of the Association for International Affairs (AMO), said in an interview. “They are quite visible in the opposition, and they are in power in nine out of 13 Czech Republic regions as a result of local elections.”

The only progressive party in the Czech Republic

Once criticised broadly as a “single-issue party” after their founding around policy related to digitalisation and cyber security, the Pirate Party in the Czech Republic has come to stand for progressivism, green issues and industrial modernisation.

“In thinking about what makes them so special and so different and how it is they've managed to gain so much in just a decade, what it comes down to is that they really are the only relevant progressive party right now in the Czech Republic,” Jana Juzova, Research Fellow with the EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy, said in an interview.

“They’re the only liberal, progressive party which tries to address green issues, job opportunities for young people, and human rights issues. These things aren’t really mainstream topics in Czech politics, so that makes them stand out.”

Ivan Bartoš. Credit: Pirátská strana

Juzova says their appeal is especially strong with young people, who make up a large part of the educated voter base in the country and see Pirates as the source for “much-needed change in Czech politics.”

One of the issues most important to that voting bloc is the environment. “This is a global trend. Our generation is more concerned with topics that were not really concerns for our parents' generations,” said Juzova, who points out that five years ago, even some of the most important and prominent politicians were climate deniers.

Calling environmentalists “funny names” was commonplace, but in just half a decade that is changing. “There's this generational shift and that's why I think the Pirate Party got so much stronger.”

Their power base includes the mayor of Prague, where the non-profit AMO is based. But despite growing support on a local level, success hasn't been easily won on a national scale for Bartoš and his Pirates.

A country at a crossroads

Looking at Bartoš – either suited and seated in a black leather chair in Brussels while visiting the European Parliament or standing behind a DJ table during a Twitter livestream in Dolánky – it’s easy to see that in many ways, the election taking place in the Czech Republic is a generational stand-off.

Incumbent Babiš was born in 1954 – back when the United States was deciding whether to allow mixed-race schools, Elvis Presley cut his first commercial record and gas was 29 cents in the US.

The son of a Communist diplomat, Babiš made a fortune in newspapers, becoming the second richest man in the country – wealthy enough to buy a mansion in France the legal way, opponents might argue.

Meanwhile, Bartoš’ parents left teaching and construction jobs to become bank tellers in order to finance an opportunity for their son to study abroad in the US, which Bartoš believes was fundamental in shaping his worldview.

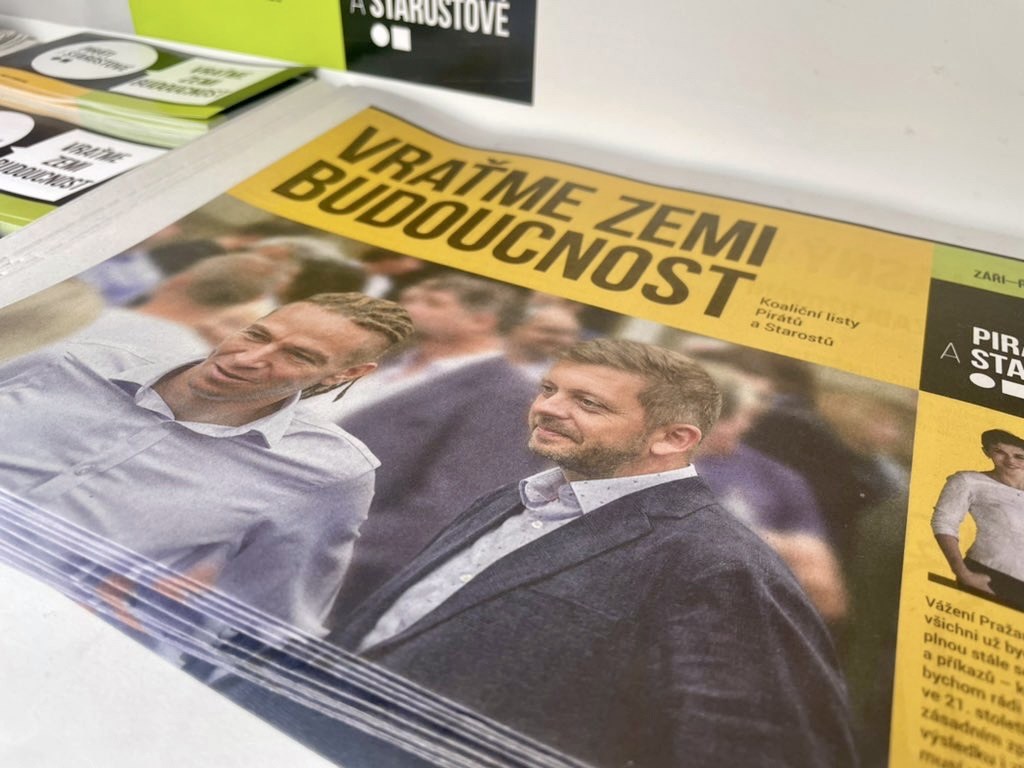

Campaign materials for the Pirate Party were being handed out in Prague ahead of the election. Photo by Helen Lyons/The Brussels Times

“Going abroad for at least half a year is the most important thing in education, career, or any part of life that a person should go through,” he said in an interview.

“It gives you perspective, it gives you global views on issues. You can be very critical about someone, or very negative about the citizens of the country, but it’s not citizens who are behind bad policy, it's usually the government. It's important to meet people, and experience that.”

He points to China as an example, saying that even if one despises the decisions made by its government, “you have to understand what the ordinary Chinese person is going through in his life.”

International policy is one area that deeply divides Bartoš and Babiš. Bartoš wants to abandon the Visegrad Group (a cultural and political alliance between Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) in favour of strengthening ties with progressive Western European countries.

Whilst many in the Czech Republic still regard the Visegrad Group as the basic stepping stone for integration with the EU, Juzova explains that over the last year it has come to be seen “identification with Hungary or Poland, and the Pirates realize how toxic this image is” – especially in light of the ongoing investigation of Hungary's rule of law violations.

“They want to completely depart from it and search for other countries and parties in the EU, probably in the west and north, who are democratic and support human rights. That would be a big change.”

Covid-19 and “the migration card”

The coronavirus has also complicated this year’s election. Given the various successes and failures of the incumbent administration throughout the pandemic, Musalkova says that the primary criticism of the Pirate Party lacking leadership experience can also be seen as a plus.

“I think that their biggest advantage at the moment is that they’ve never led the government, so they don’t have a bad track record. There’s still a lot of hope around them.”

She says that one of the biggest impediments to success for the Pirates in the election taking place on 8 and 9 October is also one of the hardest to overcome: disinformation. Unsubstantiated allegations are spreading on social media, “mainly about the Pirate's stance on migrants, which isn’t based on any actual policy” but nonetheless is proving effective at debasing the party.

Disinformation also had a significant impact in the last presidential election, Musalkova says, when a last-minute billboard campaign ran an anti-migration message: “This country is ours.” This swayed a close election in favour of the staunchly anti-migrant Miloš Zeman, just three days before the vote. “It’s ridiculous, of course,” said Musalkova. “I felt ashamed when I read it.”

Translation: In 2011, Andrej Babiš shouted that he had nothing in tax havens. In 2015, he repeated it in the Chamber of Deputies. This week he changed his statement about 5 times. I look forward to the trial. Especially to see how Babiš will prove the transparent acquisition of his villas in France. Only there it won't be "babishow" anymore.

She and Juzova both maintain that the Czech Republic doesn’t have a migration problem – in fact, the country doesn’t have many migrants at all. “In the Czech Republic, migration never really was an issue,” said Juzova, who points out that the already-low number of refugees in the country has been steadily declining. “Still, it resonates so strongly in society. You can score some cheap political points with this topic in the Czech Republic.”

Text messages sent to Czech voters claim that the Pirates and Bartoš himself “are trying to push through legislation that would move migrants into people's apartments against their will if they win the election.”

The lack of truth behind the claims hardly matters. It forces Bartoš to spend valuable campaign time refuting false narratives, rather than promoting his platform. “It's ridiculous, and it’s got to be exhausting and difficult for them to continuously be fighting-off disinformation, both because there's so much of it and because it’s so ridiculous,” said Juzova.

Leading with the facts

Bartoš tries to shrug some of it off. “It's easy to judge someone if you don’t know them or haven’t experienced their perspective,” he said. “Some people go through life understanding the world through headlines.”

“Everyone has a right to be a little conspiratorial, but I sobered up on those feelings when I became a target – reading false stories about yourself when you know the truth.”

In the end, an election that represents a decade of progress for the Pirate Party may come down to which of these three issues matters most to voters: the handling of the coronavirus pandemic, attitudes towards migration, or the corruption revealed by the Pandora Papers.

Whether the election is won or lost, Bartoš says “the work isn't done.”

“Politics is a tool to introduce a change, it’s not the change by itself,” he said. “That's a belief I'm fully dedicated to.”