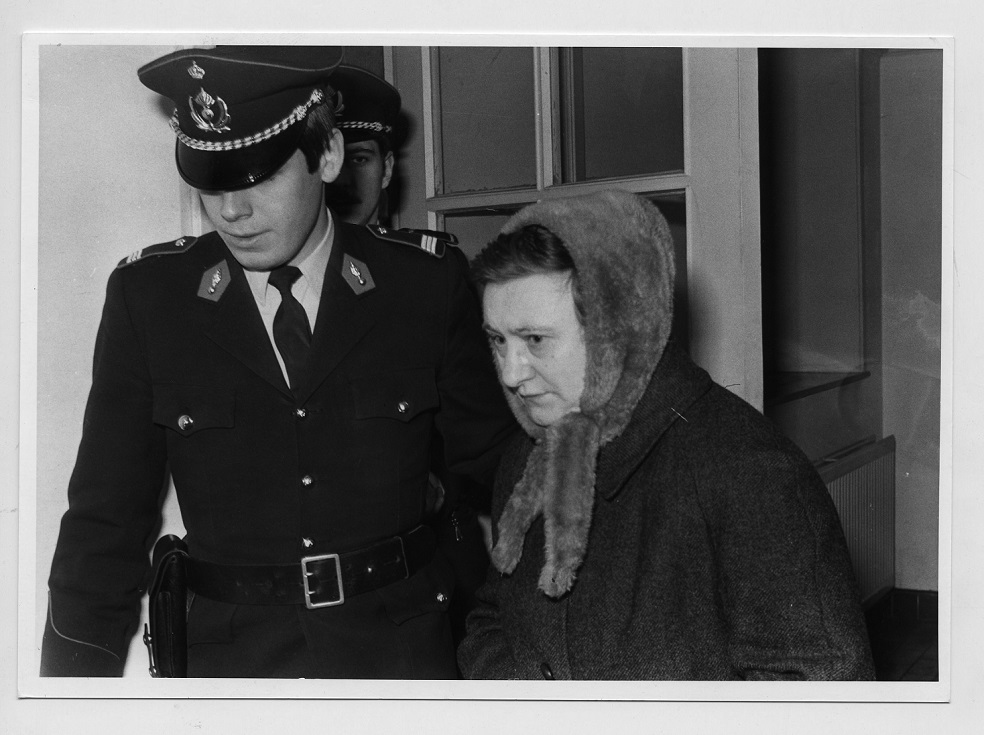

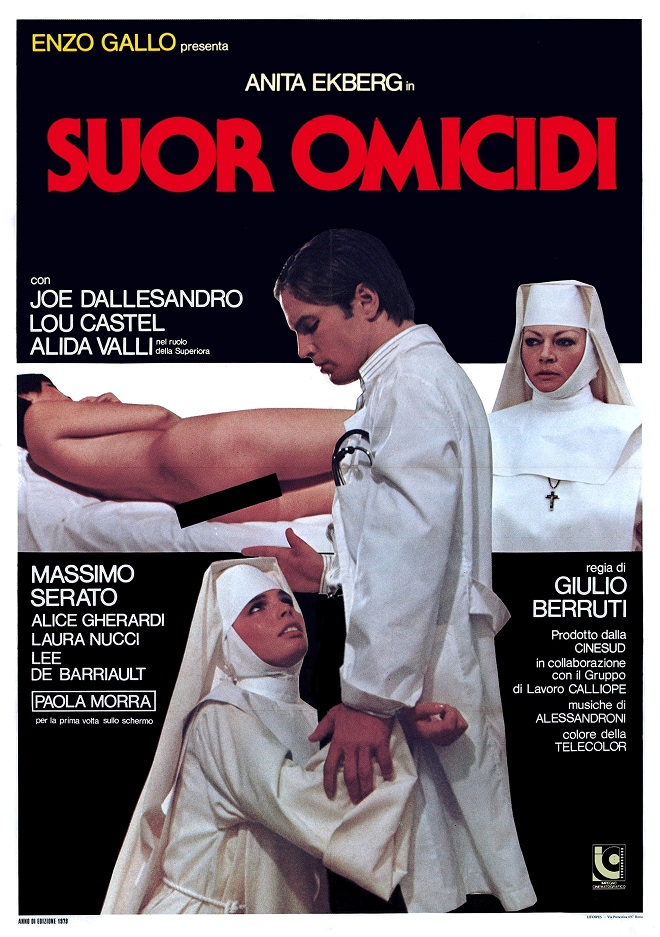

Described as short and plump, plainly dressed Sister Godfrieda did not stand out, apart from the fact that she wore a nun’s habit. But after she was arrested for a series of murders in the picturesque Flemish town of Wetteren, she became the subject of lurid stories around the world, in magazines like Paris Match and Time, and would eventually be portrayed in a nunsploitation movie by Swedish sex bomb Anita Ekberg.

Godfrieda’s sensational story began in modest circumstances. Born Cecile Bombeke in 1933 into a Catholic peasant family in Wichelen, she was 24 when she arrived at the convent of Apostolic Congregation of St Joseph in Wetteren, some 10km east of Ghent.

It was there that she took on the name Sister Godfrieda and began working as a nurse at the geriatric ward of the nearby retirement home. Known as ‘the Chronic’, this is where the most sick and needy residents of the nursing home lived. Some had to be treated for hellish pain, while some were so weak that they barely moved.

Godfrieda was seen as dutiful and devout, and in 1967 was appointed head nurse of the department, directing a small team of helpers. She was the only nun at the Chronic: all other staff members were lay people.

But from 1970 onwards, Godfrieda started to complain about severe headaches. Unable to find the cause, the doctors prescribed painkillers. The medicine soon became a crutch: Godfrieda needed more and more to keep working, and her mother superior, anxious not to lose her, would turn a blind eye to the painkiller addiction.

When the agonising headaches became too much, Godfrieda went to see Ghent neurologist Jules Govaert: he diagnosed a malignant tumour in her brain, and it would be removed in a 1974 operation.

Changing behaviour

However, the headaches continued. Govaert prescribed her a heavily sedating and highly addictive morphine derivative, which she was allowed to take on a limited basis. Although Godfrieda returned to the Chronic, she barely functioned. Sinking further into her addiction, she began stealing drugs and falsifying prescriptions.

The brain surgery changed her in other ways. She began drinking. She took fellow nun, Sister Mathieu – with whom she had a lesbian relationship – to fancy restaurants, cafés and sex shops. She bought provocative clothing and made sexual advances toward her female staff.

More disturbing was her behaviour with patients. On three separate occasions, staff caught Godfrieda as she pressed hard on an elderly person's chest and then made them drink water, a process that fills the airways with water and can result in drowning.

At the same time, jewellery, cheques and cash began disappearing at the Chronic.

And, most alarmingly, people began dying in mysterious circumstances.

On July 29, 1977, 81-year-old Leon Matthys complained about his digestion after breakfast. He received an injection from Godfrieda. And then he died in the afternoon. He was just one of many: 21 people died at the Chronic in 1977, compared to the ward’s annual average of 13.

Some of the nurses began compiling a secret diary about the peculiar goings-on there, listing not only the deaths but also what appeared to be extreme maltreatment of old people. They approached the chair of the hospital, Romain Verschooris, with their suspicions, but he dismissed them as “foolish bitches…plotting against Sister Godfrieda.” Yet shortly after the meeting, on August 14, 1977, 79-year-old Irma De Backer died. She had been sleeping badly for several nights, and Godfrieda had given her an injection that afternoon, but in the evening, she was dead.

At this point, Verschooris recognised that the situation was problematic, to say the least. After sending Godfrieda to a rehab clinic, he told staff members to keep quiet about the incidents, arguing that no one was served by a scandal, and that what happened could not be reversed anyway.

Arrest and confession

With Godfrieda out, Wetteren returned to its regular routines. But four months after her departure, Godrieda sent a Christmas card to the staff, with “See you soon” written on it. She wanted to go back to her former position.

Realising that a better solution was needed, three staffers approached Jean-Paul De Corte, a young general practitioner with a reputation for discretion to tell him about Godfrieda's murders, thefts and addiction. De Corte was persuaded but needed proof, which he found when an agent monitoring pharmacies in the region confirmed the prescription fraud.

Godfrieda was arrested on February 10, 1978, initially on forgery charges. But she soon confessed to three murders with overdoses of insulin: De Backer, Matthys and the 87-year-old Maria Vanderginst. She said they had been "too difficult at night," but she did it "sweetly," she insisted, and none of the three had suffered. De Corte added: "It could just as well be 30 people as three."

Belgian police formally charged the nun with three murders, and a judge ordered crews into the graveyard to exhume not only the bodies of the three patients that Sister Godfrida admitted killing but also those of seven other possible victims).

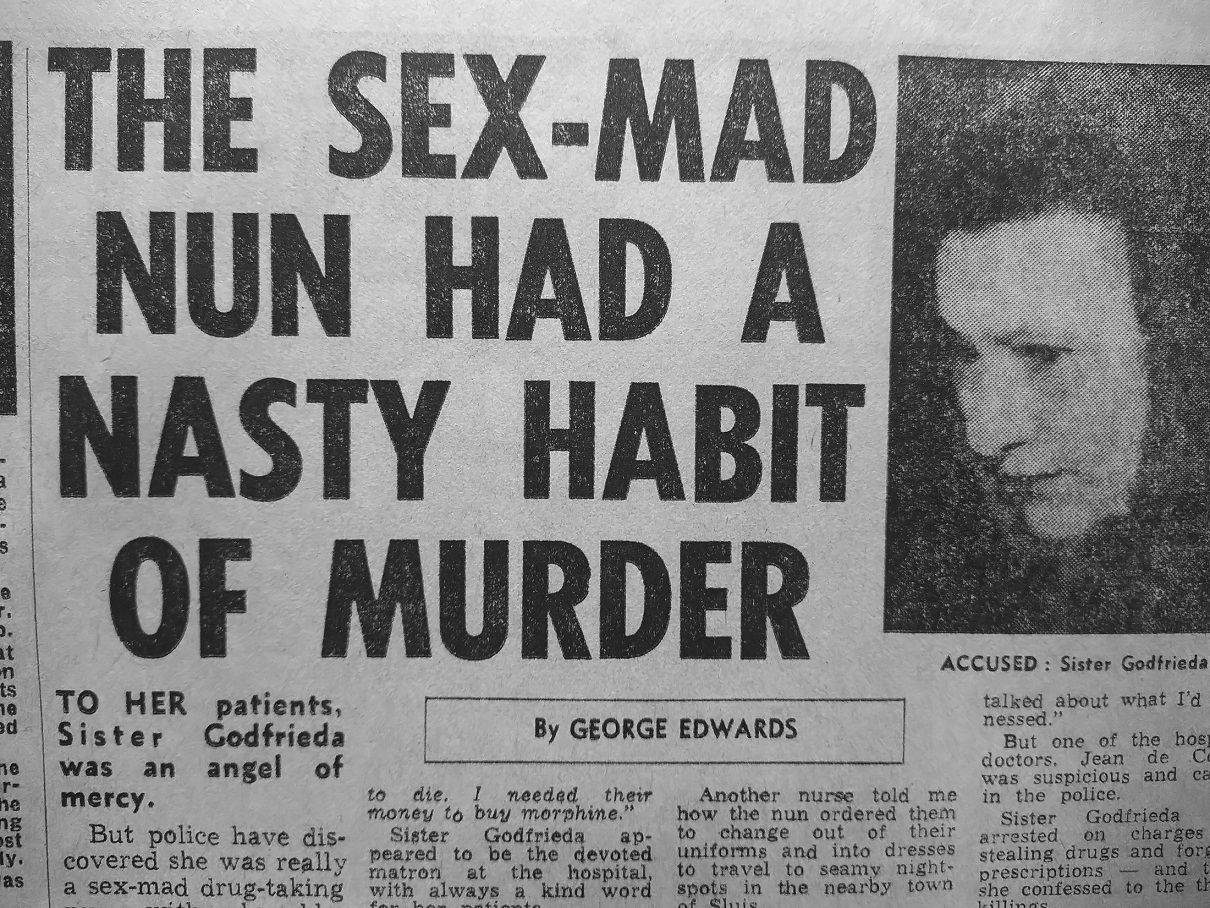

While the news barely made a ripple in Belgium, where the mainly Catholic papers mostly ignored it, the world press descended on tiny Wetteren. A nun sold photos of Godfrieda to German journalists, a Japanese photographer sneaked through the garden of her parents, and the stories were splashed across tabloids and glossy magazines. An added element of luridness was her reputed simultaneous sexual relationships with both Sister Mathieu and a retired missionary priest.

The headline in The Sun

The story would later be turned into the schlock Italian nunsploitation movie, ‘Suor Omicidi’, (entitled ‘Killer Nun’ and ‘Sister Murders’ in different English releases), with Ekberg as morphine-addicted nun Gertrude recovering from surgery and mistakenly assuming she was behind a spate of murders.

Anita Ekberg playing Sister Godfrieda

As for the judicial processes, an investigating judge, Leo Tas, was appointed to find out how far Godrieda went. He arrived at a list of 17 people whose deaths Godfrieda could have had a hand in. The list has never been made public until my book ‘Soeur Mourir’, published this year.

However, Tas only had statements and circumstantial evidence. In the case of Gabrielle De Mol, her son-in-law told the police that Godfrieda had predicted that she would die on Christmas Eve 1976 – which turned out to be the case. "At the time, we thought 'How can those nuns predict that so accurately?' Only now do we realize that perhaps her death was not natural,” he said. While this sounded odd and suspicious, it was still not proof.

Godfrieda denied that she deliberately killed Matthys, Vanderginst and De Backer. She just wanted to calm them down, she claimed, and had nothing to do with other deaths.

Unneeded surgery

At the same time, a board of experts was set up to determine whether Godfrieda was guilty. They reached a striking conclusion that, again, was never made public until now: she did not have a brain tumour.

While Govaert told Godfrieda – as well as her family and her other doctors – that there was a growth, the report of the surgery makes no mention of a tumour, nor did the scans suggest one. The report concludes that Godfrieda probably had chronic encephalitis, a curable condition.

Was Govaert too hasty in proceeding to surgery? My theory is that he found no tumour, but pretended he did to explain the major damage to her skull. However, we will never know for sure, unfortunately, as the neurologist has since died.

Nonetheless, the effect was significant. Godfrieda thought she was dying, numbed herself with morphine and alcohol, lost her inhibitions, and worked off her frustrations on defenceless patients. She also rebelled, going out into the world as ‘Madame Cecile’ and enjoying life to the fullest while she still could.

By 1980, the experts finally reached a conclusion about Godfrieda: she was ruled insane. The decision meant she avoided a public trial that would have raised awkward questions for neurologist Govaert, the Mother Superior, the doctors who gave her ever more morphine and Verschooris.

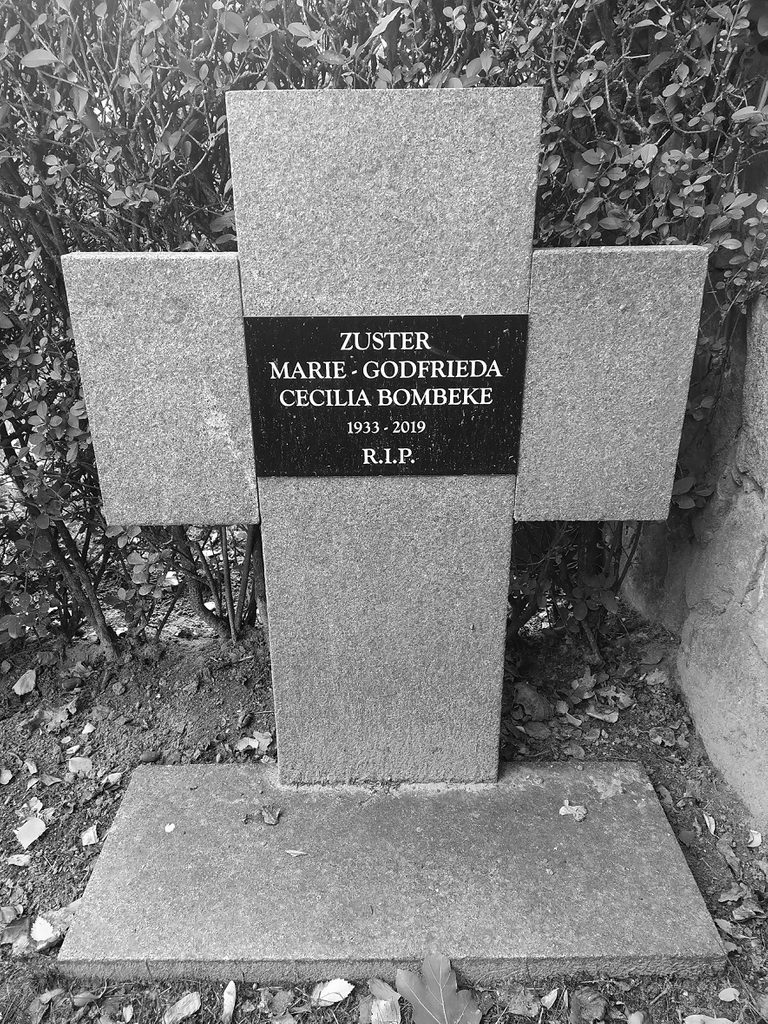

Her grave

Interned in a psychiatric institution in Melle, Godrieda would be released in 1990, returning to the convent in Wetteren. Eventually, it was her turn to go to an old people’s home, where she lived her final years in a state of dementia. She died quietly in 2019, aged 86. Even her family was not notified of her death. Only three people were at her burial: the priest, the dean and the mortician.

Her grave is at a small nun cemetery in the woods behind the former convent building. The gold lettering on her tombstone reads: Sister Marie-Godfrieda, Cecilia Bombeke, 1933-2019. It is the final resting place of the woman portrayed by Anita Ekberg, who killed at least three but possibly 17 elderly people, and who is better known in, say, Sweden, than in her native Belgium.