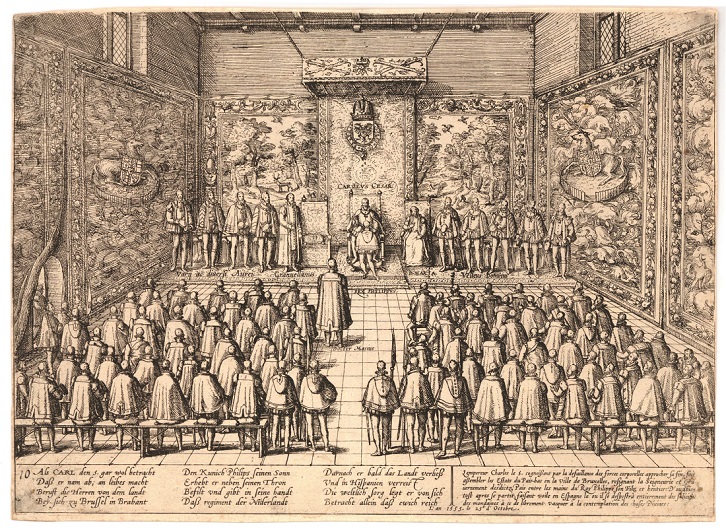

On October 25, 1555, the grandees of the Habsburg Netherlands gathered in the Great Hall of the Coudenberg Palace in Brussels to witness an extraordinary event. A weary old man with a grey beard and a limp shuffled into the room to deliver a speech that would change the course of the land.

The man was Emperor Charles V. Now aged 55, he was tired of spending his days rifling through papers of state and worrying about Protestant upstarts. He, therefore, announced he would abdicate as Lord of the Habsburg Netherlands, in favour of his son Philip.

Almost 40 years previously, the Coudenberg Palace was also the scene of a ceremony for Charles: in 1516, he was then officially declared an adult and thus ready to rule over the Hapsburg Empire. But after almost four decades, he was worn down. He put on his glasses and told the assembled crowd about his extraordinary yet often tragic life, while also asking forgiveness.

His audience was stunned. Charles then departed the Great Hall and retired to his chambers. The most powerful man in Europe had given up.

Charles’s story began on February 24, 1500, at the Prinsenhof Palace in Ghent when he was born as the son of Philip the Fair, ruler of the Habsburg Netherlands and Joanna of Castile, daughter of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon. The young boy was named after his larger-than-life great-grandfather, Charles the Bold who had died in battle fighting the Swiss at Nancy in 1477. He was the latest addition to the powerful Habsburg family, the clan that was slowly but surely gaining footholds across Europe, amassing a formidable collection of crowns.

Charles did not have a stable family life. His father died young, and his mother would be labelled mad (she wandered around with the coffin of her husband) and spent the second half of her life confined in a Spanish castle whilst others ruled in her stead.

Dutch cursing

Young Charles was raised at the court of his aunt, Margaret, who ruled the Habsburg Netherlands as regent from Mechelen, having relocated her court from Brussels, the place where scheming aristocrats stalked Coudenberg.

Now, Charles and his siblings were brought up in one of the most sophisticated courts in 16th century Europe. Mechelen was where thinkers like Erasmus and painters like Albrecht Durer would confabulate. Charles’s education was overseen by Adriaan of Utrecht, who would later become Pope Adrian VI, who urged him to lead a simple life; and William of Croÿ, who taught him chivalric principles.

Charles learned to speak French, Latin and some Diets (an old version of Dutch), though he was not an apt student. Contemporary accounts said he preferred to swear in Dutch, which he probably picked up from his servants in Mechelen.

Charles meeting with France's François I

By the time he was six, Charles was already Lord of the Netherlands, a collection of semi-autonomous states that included Flanders, Brabant and Holland. When he was 16, he became co-monarch of Spain and its many dominions. And by 19, he would become Holy Roman Emperor, a title he acquired after bribing the princes who were the electors. Before he had even reached 20, he had become the most powerful man in Europe.

Charles’s rise was due to many factors, but charisma was not one of them. He was gifted with a characteristic Habsburg feature: a massive jaw. This infamous ‘Habsburg chin’, the result of generations of inbreeding, prevented Charles from eating properly: envoys to the courts in Mechelen and Brussels remarked on his drooling, open mouth. Charles was painfully aware of his awkward trait: he grew a beard to conceal the chin and would eat alone. In later years, he also suffered from severe gout which made walking difficult.

Reign in Spain

As Charles’s empire grew, he reluctantly embraced the lifestyle of a wandering monarch. After the death of his grandfather Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1516, he was declared king of the many Spanish crowns at Brussels’ St Michael and St Goedele’s Church. However, it would take Charles another year before he would make his way to Spain, his supposed mother country.

When Charles finally arrived, the Spanish locals resented how his retinue was mostly composed of noblemen from the Low Countries – and that he barely spoke Castilian. Nor did Charles – or Carlos in Spanish – help his cause when he appointed William of Croÿ, cousin of his adviser, as Archbishop of Toledo, the most important sea in Spain.

After he was elected Holy Roman Emperor, Charles set off for Germany, leaving as regent Adriaan van Utrecht, who promptly raised taxes. This eventually led to a rebellion known as la Guerra de las Comunidades de Castilla. Though the uprising would be brutally suppressed, Charles would also appoint more Spaniards to his court.

Charles’s rule in the Low Countries was also mixed. He started well with many ‘joyous entries’ – medieval ceremonies for new Belgian monarchs – in the various capitals, where he swore to uphold the rights and privileges of the regions he visited.

But he antagonised the locals when he dragged his Spanish-born son to the court: his heir, the eventual Philip II, would be seen as both aloof and a bore. And Charles indulged himself, notably during his visit to his sister’s favourite residences in Binche and Mariemont: known as the ‘Triumph of Binche’, Charles’s extravagant party lasted eight days, during which they were treated to lavish spectacles including a mock siege.

Charles rearranged Low Country institutions as he pried the Habsburg Netherlands out of the Holy Roman Empire – the very same organisation he formally ruled – through the Burgundian treaty of 1548, also known as the Transaction of Augsburg. He later decreed the Low Countries were one and indivisible and created central institutions (Council of State, Council of Finance and Privy Council) that would aid the regent in his absence.

At the same time, he had to cope with the rise of Protestantism, which he tried to crush. And in his city of birth, Ghent, locals revolted against the taxes for his wars: they, too, were smashed, and Charles also ordered the destruction of ancient St Baaf’s abbey. Even today, the people of Ghent are now known as ‘noose bearers’, recalling how the city elders had to march with nooses around their necks to the Prinsenhof Palace as they begged Charles’ mercy.

Wars and revolts

Charles had to contend with semi-constant war with France, usually over who would control Italy. Sometimes Charles would win – he even captured Francis I and his son at the Battle of Pavia in 1525. And sometimes he lost, like when he failed to retake Metz in 1553.

While Charles butted heads with France, he also had a love-hate relationship with England’s Henry VIII, whose first wife Catherine of Aragon was a cousin. Charles craftily lured Henry VIII into alliances, promising the Tudor monarch support in the latter’s never-ending quest to take the French crown. However, he had no desire to replace the fitful Francis with the even more erratic Henry.

Another foe was the Ottoman Empire, whose sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, boasted a court of equal extravagance. The Holy Roman Empire halted the Ottoman advance into Europe at the 1529 Siege of Vienna, but Suleiman later took control of southern Hungary and the Mediterranean.

Announcing his abdication at the Coudenberg Palace

Beyond Europe, Charles oversaw the Spanish conquest of the New World, including the defeat of the Aztec and Inca empires. As the conquistadors imposed themselves, and indigenous populations were decimated by disease and overwork, fresh labour was needed. Charles thought he found a simple solution in 1518 when he signed a charter authorising the transportation of slaves directly from Africa to the Americas.

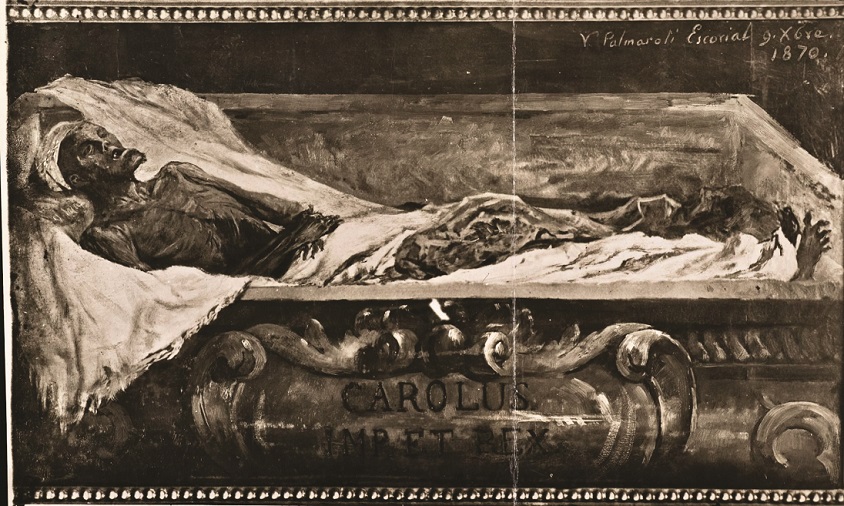

His corpse revealed, when the coffin was reburied in 1574

But it was religion that had the biggest impact on Charles’s reign. In 1517, Martin Luther wrote his 95 Theses, kicking off the Protestant movement that would challenge the Catholic Church. Charles felt it was his duty to stamp out what he considered heresy. He not only persecuted Protestants but also feuded with German princes who sympathised with the new teachings and even converted to the new religion.

The Lutheran German princes created the Schmalkaldic League, which led to the Schmalkaldic War. Charles eventually defeated the dissenters at Mühlberg in 1547, but by then, Protestantism was already deeply rooted in German society. In September 1555, Charles V – represented by his brother Ferdinand – negotiated the Peace of Augsburg, also known as the Augsburg Settlement, which celebrated the principle ‘Cuius regio, eius religio’ (whose realm, his religion). However, Charles saw this as a failure, and it would contribute to his decision to step away from politics.

And so it was that an exhausted Charles V abdicated in October 1555 as Lord of the Netherlands, followed by abdication of his many other crowns, including the office of the Holy Roman Emperor (although the electors did not recognise the move).

Freed from his royal duties, Charles left for Spain from Vlissingen in 1556 and settled in the Monastery of Yuste. It was an odd choice as the region was riddled with mosquitoes. Charles would eventually die of malaria in 1558. He was given a grand funeral in Brussels, but the coffin that made its way through the streets was empty: he had already been buried at Yuste (his son, Philip II, would later disinter his remains and rebury them in El Escorial near Madrid). Charles was no more, but his name has not been forgotten. In Belgium, at least, a beer has been named after him, which is a legacy of sorts.