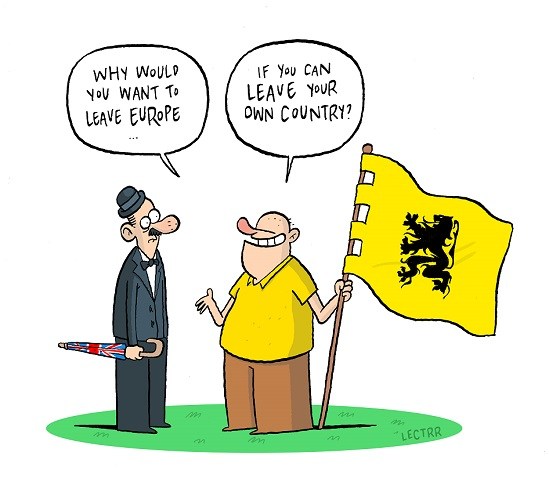

Belgium’s federal elections were held on 26 May, the same day as the European and regional elections. Most spectacular was the leap forward of the far right nationalist party Vlaams Belang (“Flemish Interest”).

It grew from 3.7 to 12% in terms of votes and from 3 to 18 seats out of the 150 in the Federal Chamber. The Flemish nationalist N-VA (“New Flemish Alliance”) lost ground but is still the strongest party in Belgium. Together, the two officially separatist parties now account for 43 out of 88 seats in the Chamber’s Dutch-speaking group, compared to only 36 before. Does this mean that the end of Belgium is near?

Only a partial and superficial reading of the results could yield that conclusion. First of all, while the most “separatist” parties made a net gain of seven seats, the net gain of the most “unitarist” parties was nearly three times larger. The far left party PTB-PVDA (“Labour Party of Belgium”) is the only party with a parliamentary representation from the whole country, and the green parties, Groen and Ecolo, are the only other political family with a single parliamentary group in the federal Parliament and a common list in the Brussels constituency for the federal elections. Together, they went up from 14 to 33 seats.

Secondly, Vlaams Belang’s hefty gain cannot be attributed to its stance on Belgium’s institutional future. This issue hardly featured in the electoral campaign, and even among Vlaams Belang voters, it comes only 9th in a list of 10 themes voters were asked to rank in a post-electoral survey conducted by an inter-university research team. Migration, security and social protection played a far greater role in the campaign, and Vlaams Belang’s gain at the expense of the N-VA had nothing to do with its institutional platform and far more with a social platform quite close to that of the PTB-PVDA: higher minimum pension, lower retirement age, social assistance lifted to the poverty threshold, less taxation of lower wages. Thirdly and most importantly, calling the N-VA “separatist” has become seriously misleading.

Don’t the statutes of the N-VA state that its objective is an independent Flanders?

They do. But they are nearly twenty years old. In the course of a pre-electoral debate with Ecolo co-president Jean-Marc Nollet on 3 April, Bart De Wever, the N-VA’s president, was asked whether Belgium still had a future. He answered: “Yes, of course, without the slightest doubt.” And he explained: ten years ago he thought that the European Union would take over many substantive competences currently exercised by the Belgian state and thereby make the latter redundant. He no longer thinks so.

Therefore, what the N-VA is proposing now is what it calls “confederalism”: more powers will be devolved to Flanders and Wallonia, but the Belgian state will survive, with a government and a parliament consisting of representatives of the two regions, and powers that will be reduced but remain significant, for example in matters of defence, security, public debt, foreign affairs and representation at EU level.

Can one then at least interpret the results of the election as providing further ammunition to those who support such a “confederalism”? The growth of Vlaams Belang makes the political landscapes in the North and in the South even more different from each other than they were before the election. This seems to confirm the view often expressed by Flemish nationalists that Belgium consists not of one but of two increasingly separate and divergent democracies and therefore needs to be restructured along confederal lines.

There is obviously no strict equivalent to Vlaams Belang in Wallonia, even though the post-electoral survey revealed a surprising similarity between the profiles of the Vlaams Belang voters and those of the Walloon wing of the far left party, PTB. But the rise of Vlaams Belang should not make us fail to see the remarkable, indeed to my knowledge unprecedented, parallelism between what happened this time in Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels. Next to Vlaams Belang in Flanders, the big winners in all three regions were the far left party and the greens.

By contrast, the three traditional political families — Christian-democratic, liberal and socialist —, which used to jointly appropriate 100% of the seats until some decades ago, all shrunk to practically all-times low levels in each of the three regions, now totalling less than 50% of the seats for the first time in Belgium’s history.

But even if the results had unambiguously supported the “two democracies” thesis, they could hardly be interpreted as further support for the N-VA’s “confederal” project. True, the officially separatist party Vlaams Belang gained most of the votes that the N-VA lost. But Vlaams Belang is fiercely opposed to the N-VA’s confederalist project, which involves the devolution of Belgium’s federal social security system to Flanders and Wallonia. Brussels residents would be required to opt for the Flemish or Walloon system. Both their rights (including pensions, education, health care and parliamentary elections) and their obligations (including social security contributions and personal taxation) would be determined by this choice.

Such a confederalism is consistent with the horizon of an independent Flanders and Wallonia jointly governing Brussels — the “condominium” that featured in N-VA’s programme some years ago. But it is inconsistent with Vlaams Belang’s overt objective: an independent Flanders with Brussels fully appropriated as its capital — if need be with some residual “linguistic facilities” for its francophone population.

By comparison, the N-VA’s confederalism seems quite moderate. Might it not have a chance as a compromise? After all, the N-VA insists that devolving social security to the Regions need not mean the end of inter-regional transfers, providing they are “transparent”.

This confederal project is intellectually stimulating, but it suffers from what you could call a philosophical flaw. Its rationale rests on the premise that democracy can only function at the level of a nation, i.e. at the level of a population which, thanks to a common language, can share a culture that does not reduce it to some abstract principles.

Among the components of the Belgian federal state, only Flanders and Wallonia are potential nations in this sense. The population of Ostbelgien — the 80,000 residents of the nine municipalities that form the German speaking Community — is too tiny. The population of Brussels — 1,200,000 residents, over two thirds of whom are either foreigners or of recent foreign origin — is too diverse. Undoubtedly, reliance on a nation makes it easier for a democracy to function. But it is not indispensable.

What a democracy does need is a demos, a population comprising enough citizens able and willing to talk to each other about their common destiny and shape it together, sometimes despite deep linguistic and cultural differences. In the decennia since their creation as federated entities, Brussels and Ostbelgien have shown that they satisfy this condition. After last May’s regional elections, they even managed to form a government long before Flanders and Wallonia.

Hence, if there were any confederalism worth taking seriously, it would need to have four components, not two. Needless to say, a “confederal” regime that would give a veto right to four components would be even less workable than one with just two components. Moreover, unlike the N-VA’s two-part confederalism, such a four-part confederalism is of no interest for those who are seeking a way of granting more autonomy to Flanders without weakening its grip on Brussels.

If no version of confederalism has any chance of emerging as an acceptable compromise, it seems that it will again take a long time before the next federal government is formed.

I am afraid you are right. There are institutional reforms that could address the structural causes of such deadlocks and thereby help our multilingual country function much better. I sketched what I believe to be the crucial ones in my book Belgium. Une utopie pour note temps (Académie royale de Belgique, 2018; Dutch version: Polis, 2018), but I am under no illusion that they could be adopted swiftly.

Wisdom commands that the formation of the next government should not be suspended on agreement on future institutional reforms. We need a federal government with enough support on both sides of the language border to keep the Belgian ship afloat in the coming months and years, despite the turmoil to be expected from a disorderly Brexit and the structural challenges of climate change, migration and ageing. In parallel, we need a broad, open and thorough debate, not just among politicians, about the way in which our political institutions could be improved.

The Brussels Times