In the aftermath of the turbulence of the First World War, the map of Europe was redrawn, giving birth to new nations and consigning others to the annals of history. Among these was a tiny, overlooked sliver of land known as Neutral Moresnet, one of the "micro-nations" of its kind and a testament to the complexities of European politics and Belgium's precarious position between warring alliances.

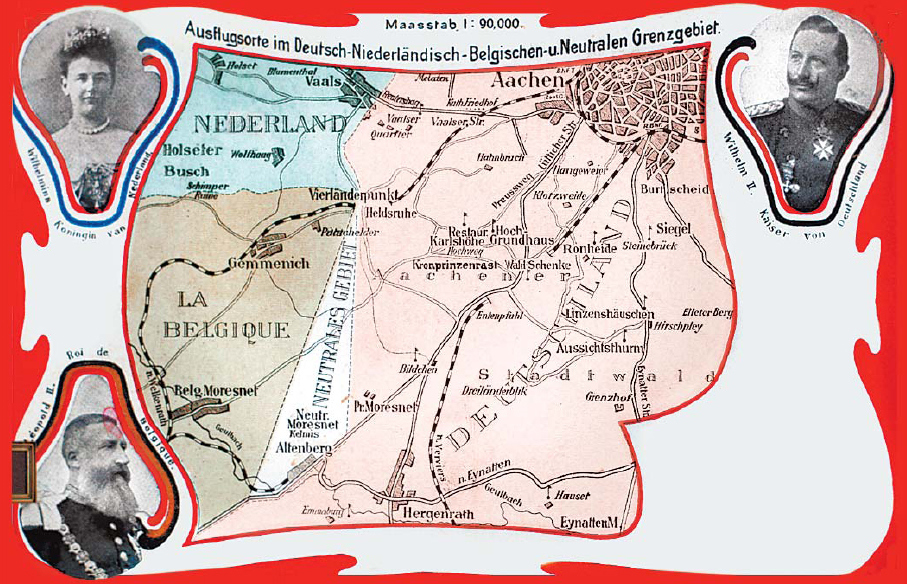

Neutral Moresnet, with its capital in modern-day Kelmis, now part of the province of Liège and Belgium's German-speaking community, emerged from a dispute over valuable zinc resources following the Napoleonic Wars.

Both the Kingdom of the Netherlands (later Belgium) and the Kingdom of Prussia laid claim to the zinc-rich territory. The Congress of Vienna, seeking a balance of power in post-Napoleonic Europe, could not satisfactorily resolve the issue, leading to the creation of Neutral Moresnet in 1816. This 3.4-square-kilometre was run as a "condominium", administered jointly by two powers but inhabited by people of diverse origins and allegiances.

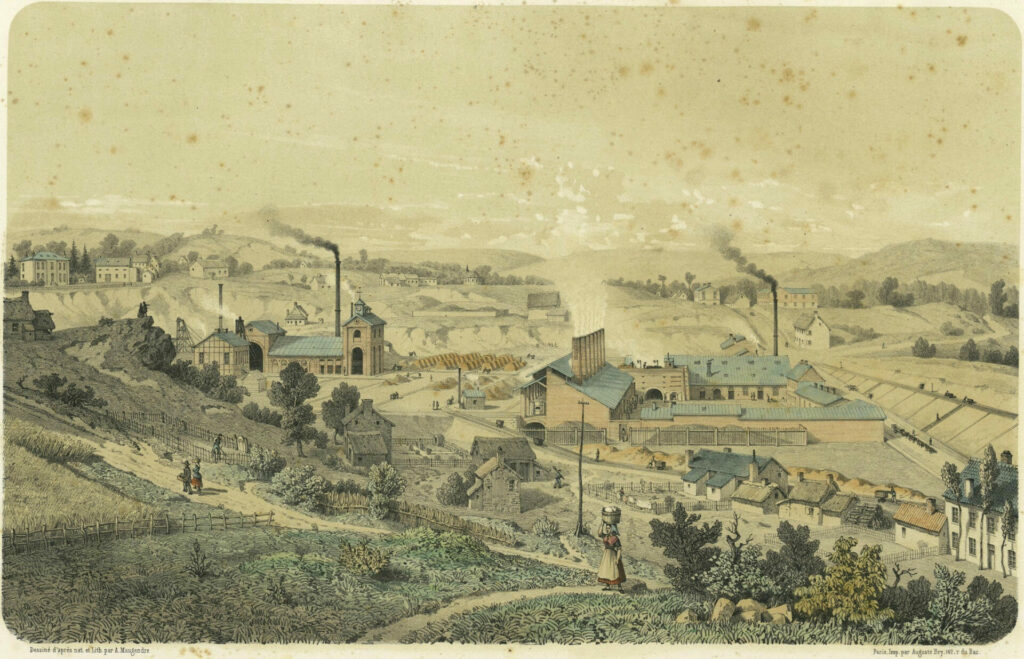

Europe's Zinc state

Life in Neutral Moresnet was shaped significantly by the Vieille Montagne mining company, the territory's main employer and quasi-governmental entity. Up to 3,500 people called Morsenet home.

"It was a company town in the truest sense, with Vieille Montagne providing not only jobs but also housing, healthcare, and commerce," explains historian Lucien Kelm in his book "Moresnet: Europe's Forgotten Nation". This unique arrangement created a blend of cultures, languages, and traditions, with French, German, and Dutch influences converging.

The residents of Neutral Moresnet enjoyed certain privileges, such as low taxes and the absence of a military draft, which attracted a variety of settlers including those seeking refuge from conscription in their home countries. However, these benefits came with the cost of statelessness for the people of Neutral Moresnet, rendering them aliens on the fringes of Europe's great empires.

The territory's unusual status gave rise to some imaginative initiatives. In the early 20th century, Dr. Wilhelm Molly, a local physician and an enthusiast of the man-made language Esperanto, proposed transforming Neutral Moresnet into the world's first Esperanto-speaking state, to be named "Amikejo" (Place of Friendship). The proposal gained some traction, with several residents learning Esperanto and the territory briefly becoming a curiosity on the world stage. However, the linguistic revolution largely fell short of its goals.

.

The outbreak of the First World War and Germany's subsequent invasion of Belgium in 1914 brought an end to Neutral Moresnet's precarious independence. Initially spared the ravages of war, the territory was eventually annexed by Germany in 1915, though this move never gained international recognition. "It was a poignant end to a hopeful experiment, as the territory was consumed by the very conflicts its 'neutrality' was meant to avoid," notes Kelm.

Becoming Belgium

The post-war Treaty of Versailles in 1919, which brought an end to the German Empire, resolved the century-old dispute by awarding sovereignty over Neutral Moresnet to Belgium. On 10 January 1920, the territory officially became part of Belgium.

Related News

- Hidden Belgium: One of the strangest places in Europe

- Fake stamps, a made-up language and a pig in a jester's hat: Let's explore Neutral Moresnet

Despite its absorption into Belgium, the legacy of Neutral Moresnet lingers on, particularly in the cultural melange that characterised its people. The Museum Vieille Montagne in modern-day Kelmis stands as a testament to this unique European historical footnote, housing exhibitions dedicated territory's industrial, cultural, and political heritage.

To find out more about the history of this forgotten corner of modern-day Belgium, plan a visit to the Museum Vielle Montagne. Kelmis can be reached in around 2 hours from Brussels via Verviers or Aachen in Germany.