Jesus Christ took his last steps on earth in Ostend, Belgium.

This ‘fact’, as it stands, is laid out in French novelist Honoré de Balzac’s 1855 work, Jésus-Christ en Flandre, a short story in which Christ disguises himself to board a ship of Flemings bound for the Belgian coast. When the vessel is set upon by a storm and capsized, Christ leads the pious over the waves and to the safety of the beach, where his final footprints in the Ostend sand became a holy relic until, inevitably, the next border conflict saw them borne away and lost forever.

Apart from the expected lessons to be had from the “quaint legend of old Flanders,” as de Balzac describes it – the greedy passenger drowns trying to save his gold, the scientist scoffs at religion and is swallowed by the sea, an unchaste woman is pulled to a watery grave by her lover – there is a more provocative conclusion to be drawn from the work: Jesus doesn’t like the Flemish.

Told to him by his father, it was one of James Ensor’s favourite stories.

Ensor’s origins will be familiar to many: British father, Belgian mother, school here and summers there. Family members who could not address each other in the same language, child interpreters filling the gaps.

Ensor’s father never mastered the delicate balance of a life between two heritages. An intellectual, James the senior studied engineering in England and Germany before settling with his wife in her comparatively sleepy hometown of Ostend, just one small city block between their front door and the coarse sand that absorbed both the tides of the English Channel and the weight of Jesus Christ the Saviour Himself. The elder James had a vast library in his home, a mark of his curiosity and his cultivation. His new Flemish neighbours welcomed neither.

But for the younger James Ensor, the library was a playground for his imagination. In it, he poured over texts from philosophers and engineers, politicians and artists. His father poured liquor. When treading a fragile tightrope between different cultural identities, and attempting to assimilate, it’s easy to teeter and fall.

“As soon as the man appeared on the jetty to which the boat was moored,” Balzac writes, “seven persons who were standing in the stern of the shallop hastened to sit down on the benches, so as to leave no room for the newcomer. It was the swift and instinctive working of the aristocratic spirit, an impulse of exclusiveness...”

In Balzac’s story, Christ eventually found a place for Himself amongst the poor and working class onboard, and even managed to survive a miscommunication in which an Antwerpaar perceived a slight to his city (“C’est le diable – il se moque de la Vierge d’Anvers!”). But James Ensor’s father never found a place in Belgium, and the son would spend much of his own life feeling – and indeed, being – similarly misunderstood and rejected by people whose approval he wasn’t entirely sure he wanted anyway. Like so many artists who dare to disrupt, provoke, tantalise, even repulse, appreciation from his countrymen came late in life and brought little joy.

There was surely some comfort and vindication to be found in a story in which Christ himself came to Flanders, and decided He did not like the Flemish.

Answers in Ostend

“You can only understand James Ensor and his art if you visit Ostend,” the museum that now occupies the artist’s home declares. But Xavier Tricot, curator for Het James Ensorhuis, or the James Ensor House, is quick to elaborate that the relationship between the artist and his home is a complicated one.

“He loved Ostend,” Tricot agrees, “but not so much Ostenders.”

An art historian and successful painter himself, Tricot is the author of James Ensor: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings. Apart from being the definitive source on all things Ensor, he’s considered an authoritative voice on art and art policy in Ostend, and accolades for his own works (displayed in London, Paris, Brussels and elsewhere) are hardly in short supply.

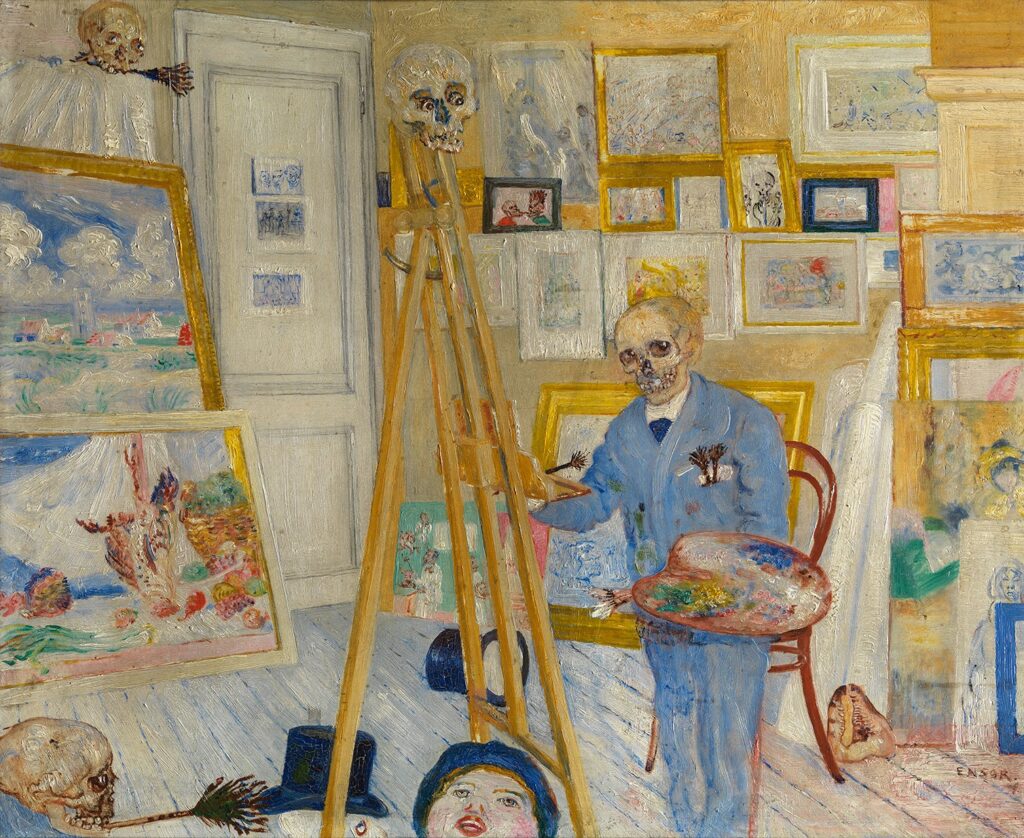

Ensor at his Easle, self-portait (1890)

So when Tricot describes Ensor – “possessing a radically novel vision”, “a true anarchist at heart”, “one of the most complex artists of the second half of the 19th century”, “without masters or disciples, completely independent” – it is not simply as a researcher or devotee but as a sort of colleague, a fellow artist, a fellow painter and a fellow Ostender.

“He’s a pioneer,” Tricot says, ticking off a list of artists who followed in Ensor’s footsteps: Heckel, Kandinsky, Klee, Nolde, Grosz, Kubin, Wols and Nussbaum.

But any trailblazing was accidental, if one is to take Ensor at his word (and Tricot will vouch for that: “He was very respectful of the old masters, you see him referring to Bosch, Bruegel and Rubens.”), and it was met with abuse.

“Despite my benign intentions, I broke all the conventions of painting,” Ensor said in a speech given at the Hotel Osborne in Ostend in 1922. “I was met with a storm of remonstration, and I have never let my umbrella go since. I am scolded and insulted, I am absurd, I am mean, bad, inept, ignorant.”

The Oyster eater (1882)

The castigation likely started early. Ensor began painting at a young age and went to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels when he was just 17, leaving three years later disappointed and without a diploma. He moved back in with his parents and used their attic as a studio, producing what is considered to be his best work there in his childhood home. He drew his inspiration from his immediate environment: the attic, his family, the streets and beaches of Ostend. When he did finally move out, it was only next door. The scenery stayed the same. And yet his work soared beyond it.

“There's a kind of European cosmopolitan aspect in his personality,” Tricot says. “It’s very interesting to see the many references to local situations, but when you view the whole of his work, it transgresses the more local aspects of what he’s referring to. When you consider the interest of Americans, Asians – people from all over the world, really, in his work, that’s evidence that he’s transgressing all these boundaries.

The skeleton painter (1896)

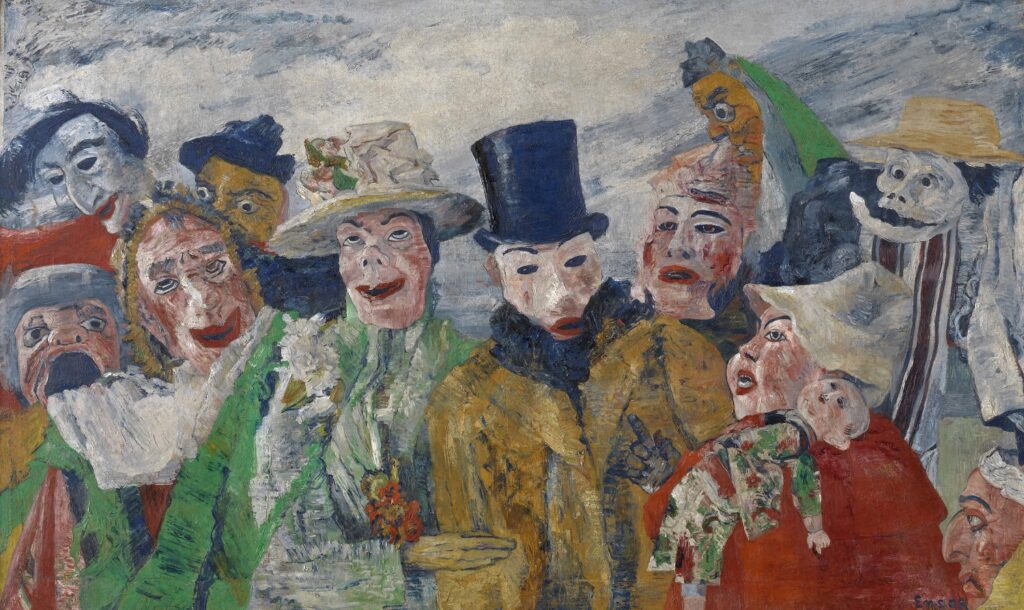

“He’s referring with his masks, for example, to Japanese theatre, Chinese theatre, to Carnival everywhere. Many people understand the references in his work. And even without that connection, you still see an interesting painter, because he’s painting in a new manner, a very spontaneous, expressionist manner. That's why he’s so avant-garde when compared with other artists from his time, for example in France and Germany.”

The intrigue (1890)

Yet Ensor is said to have rarely left Ostend, relying on a network of colleagues, clients and friends (inheriting his father’s intellectualism, he easily made them in such high places as philosophy, medicine and revolutionary politics) to get his work exhibited and sold. So from where did he draw the inspiration or substance for such pieces as Russian Music? Where did the recluse discover Japanese theatre or Brazilian carnival or British caricature? Where did the homebody develop and nurture his own political beliefs, radical as they were in his time (free public education, general voting rights)?

In Belgium, of course.

Venus at his birth

In the lonely library of his childhood home, in his mother’s curio shop, and at the annual Ostend carnival, Ensor unearthed pieces of the whole world while both feet were planted on the grey, wet beaches of Belgium. He dabbled in and then dismantled sombre realism. He conjured increasingly bizarre apparitions with oil and canvas.

“Flemish art has been dead since Breughel, Bosch, Rubens and Jordaens, stone dead,” he once declared. “Since 1830, Flemish, or rather Belgian art, has consisted of reflections and shadows…The Fleming is no longer a colourist.”

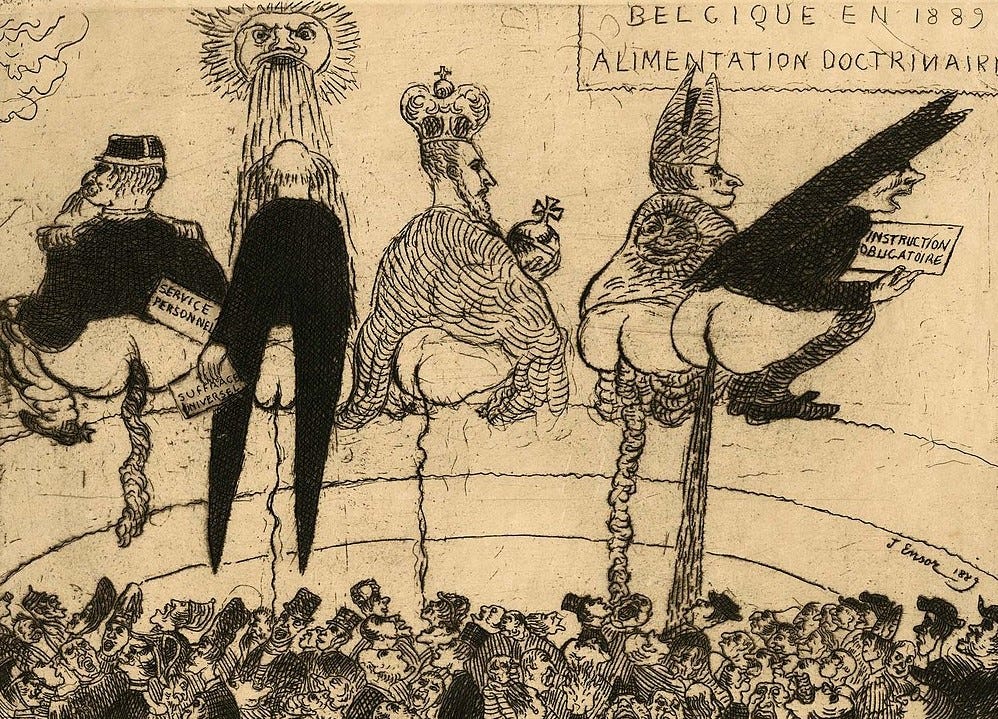

The assessment no doubt did little to endear him to his countrymen. Ensor was called scandalous, even as he lived quietly in his parents’ home painting pictures of his sister eating oysters at the kitchen table, or of the overcast Port of Ostend or a gloomy seaside street, and so then he painted himself urinating on the words of his critics. People complained that he was too political for a painter, and so he etched King Leopold II (and liberals and the Church for good measure) defecating on the Belgian populace.

Alimentation doctrine (1889)

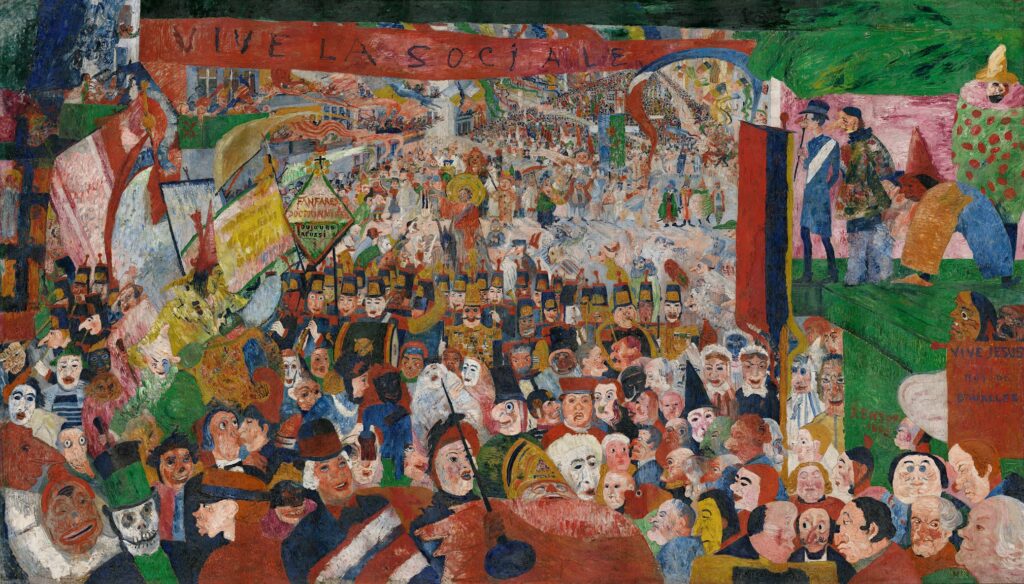

His work was consistently met with praise and perplexity in confusingly unequal measures – he was a founding member in 1883 of Les XX (indeed, it was the rejection of one of Ensor’s paintings by L’Essor Salon and the Antwerp Salon that led to the formation of the prestigious group of 20 Belgian artists), and yet they rejected what is now regarded by many as his magnum opus: L'Entrée du Christ à Bruxelles, The Entry of Christ into Brussels. It did not seem to matter.

“In the end, one gets used to life in Ostend and the ailments that affect one’s family,” he wrote in a letter to friends in 1896. “But what loneliness! How hard it is to be cut off from everything after one has had so much success! I comfort myself somewhat by working – I am constantly painting masks. They look at each other furiously, reflecting how I feel.”

Little could pull Ensor away from Ostend, no matter the abuse Ostend heaped on him in return for such loyalty. Even though Brussels was to the atheist Ensor a “new Jerusalem,” as Tricot puts it, and the home of so many of his most beloved and trusted friends, it was never enough for the painter to make his own entry into the Belgian capital. When World War II broke out and those friends urged him to leave for fear of bombardment (L'Entrée du Christ à Bruxelles, which he once vowed would never leave his studio, was damaged by shrapnel during the war), he stayed.

Christ's entry into Brussels in 1889

“He made his hometown into a place that transcends reality – it became a mythological place for him,” says Tricot. “That’s also a part of his personality, that he makes his own mythos – wherever he lived, in Ostend or Brussels, he made his own mythology. Even his birthday became something mythological.”

Of that, Ensor wrote: “I was born in Ostend on April 13, 1860, a Friday, the day of Venus. At my birth, Venus came to me smiling and we looked each other in the eye for a long time. She had a wonderful scent of the salty sea.”

Homebody myth

Ensor’s myths echo Balzac’s, who wrote about how the Flemish made no room for Christ on their ship, looking even at each other “contemptuously” and making “a great deal of noise” within their isolated parties, talking “among themselves as though there were no one else in the boat” when they weren’t “tittering scornfully” at the Messiah in their presence, likewise bound for Ostend.

For his part – and it is a considerable one, bearing in mind his credentials – Tricot believes Ensor’s stay-at-home reputation is overblown, even if it is plastered on every museum plaque in the Ensorhuis.

Ensor house in Oostende, now a museum

“It’s a bit of a cliché, no?” he posits. “Ensor spent many months and weeks in Brussels and he travelled to England to see members of his family.”

There were also three trips to France and two to the Netherlands – all of them brief, both countries neighbours. What does seem certain is the mark Ensor left on modern art and on Belgian art – less certain whether that counted for much to him.

“Happy? I don’t know if he was really happy in life,” Tricot says. “He was a misanthropic man who suffered in his youth – he wasn’t understood, he was mocked by the youths of Ostend. He always had to struggle – to struggle to obtain, to be accepted. In the end, of course, he was accepted by many, many people and it gave him a kind of satisfaction, I'm sure. But I don't know if he was a happy man.”

It's difficult to assess, undoubtedly, 75 years after Ensor has departed.

“I think he was always lacking something,” Tricot ventures. “His sentimental life, I think, was rather poor. We don’t know anything about his sexual life – if he was gay or not gay, or even interested in sex or a relationship at all. He liked to be alone, I think. I don't know if he was unhappy. But happy? No. Something in between? It’s difficult to explain.”

Tricot has spent over 40 years studying Ensor, and perhaps even longer working with the same oil paints as the avant-garde modernist, self-taught and reliant on his imagination – his ‘vision indirecte’ or ‘indirecte blik’ – to supplement his Ostende roots.

“He was perhaps searching for something, through his art,” Tricot says of Ensor. “Many artists do. Because the reality you're living in does not satisfy you completely, so you're searching for something ‘extra’, through your own art, your own expression. Because you want to transcend your own reality and your own life in another dimension, I think.”

Ensor died in an Ostend hospital at the age of 89, his home in poor condition but his reputation at last respected by his fellow Belgians and Ostenders, who recognised him on his daily walk along the coast.

Christ may have entered Brussels to a colourful and inattentive crowd, the Messiah nearly hidden in the centre of the painting and surrounded by grotesque clowns and masked sinners, but He took his last steps in Ostend.

So did Ensor.

2024: The Year of Ensor

Several major exhibitions will be held in Belgium in honour of the painter James Ensor. Here are a few not to miss:

The Bad Physicians (1892)

ROSE, ROSE, ROSE À MES YEUX!

This Ostend exhibition is the first ever devoted entirely to Ensor's still lifes, tracing the evolution within his oeuvre and within the history of still life in Belgium.

Some 50 works by Ensor are placed alongside a hundred or so mostly unknown, rarely or never publicly shown still lifes illustrating the development of the visual genre in Belgium.

The 150-piece collection provides an overview of the 19th-century, academic, decorative tradition from Antoine Wiertz to Frans Mortelmans, including oft-forgotten painters such as Jean Robie, Hubert Bellis.

Until April 14, 2024

Tuesday to Sunday from 10am to 5:30pm

Romestraat 11, 8400 Oostende

€15 admission

JAMES ENSOR. INSPIRED BY BRUSSELS

Skeletons tussel over a smoked herring (1891)

Discover how Brussels became Ensor’s ‘new Jerusalem’ in this special collaboration between the Royal Library of and the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium.

Featuring 18 paintings, 24 drawings and 33 prints, the exhibition draws from the extensive collections of James Ensor’s work at the KBR as well as from the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Belgium, all in the unique historical setting of Palace of Charles de Lorraine.

The Royal Library of Belgium (KBR)

From February 22 to June 2

Tuesday to Sunday from 10am to 5pm

Mont des Arts 28, 1000 Brussels

€15 admission

THE YEAR OF ENSOR

Ensor’s home was converted into a museum after his death. Recently renovated, the house has been painstakingly preserved in its original state, with rooms decorated with authentic furniture and accurate reproductions.

The museum caters to all ages, with interactive exhibits for children and an introduction to the painter’s life, work and political ideas.

Multiple exhibitions ongoing

Tuesday to Sunday from 10am to 6pm

Vlaanderenstraat 29, 8400 Ostend

€13 admission

ENSORS STOUTSTE DROMEN

With 38 paintings in its galleries, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp is home to the largest Ensor collection in the world.

Several paintings, drawings and sketches will be viewable year-round, but a special nine-gallery exhibition coming this fall will depict Ensor’s works alongside sources of international inspiration, along with his contemporaries and successors.

Sketchbooks, etches and scans will guide visitors through Ensor’s creative process from pigment to print.

Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

From September 28, 2024 to January 19, 2025

Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday from 10am to 5pm, Thursdays from 10am to 10pm, weekends from 10am to 6pm

Leopold de Waelplaats 1, 2000 Antwerp

€20 admission adults, €10 for ages 18 to 26, free for all under age 18