A major update is on the horizon for the worn-out Toison d’Or shopping area in Brussels between the Porte de Namur and Place Louise.

The plans, first proposed in 2015, have been described as the Champs-Élysées of Brussels on the Avenue de la Toison d’Or, but that’s misleading. There are three roads here running in parallel: Avenue de la Toison d’Or on the east side, Boulevard de Waterloo on the west and a multi-lane highway feeding the tunnels at each end of the site. The zone stretches across the petite ceinture, the inner ring of Brussels, and cars occupy 80% of the site’s extraordinary 75-metre span (wider than its Parisian rival).

There are just three crosswalks along its half-kilometre length, and impatient jaywalkers must pick their way through a vast herringbone of parked cars. In character, the two sides of this thoroughfare can feel worlds apart. However, the region wants to correct this.

The customary challenges for large infrastructure projects in central Brussels are in place at Toison d’Or: fateful planning decisions made centuries ago and the conversion of the city to accommodate fast automobile travel triggered ahead of the 1958 World’s Fair, Expo 58.

A permit was issued in July 2022 for a so-called ‘façade-to-façade’ renovation proposed by the Brussels region’s mobility unit with funding from the federal government. The plans will widen pavements and narrow roadways to tame but not erase the presence of cars. Six decades-worth of accumulated urban clutter will be removed and new street furniture installed to create a public space in which both locals and tourists can linger between cycle lanes.

An alternative project was launched in 2019 by a consortium of disgruntled local businesses. It criticised the emptiness and lack of greenery in the region’s scheme, proposing instead a large structure running along the middle of the road, resembling a rack filled with giant transparent eggs containing plants. It also retained much more room for cars.

Objectors in late 2023 launched a judicial appeal against the official project but this legal move was not suspensive and the work is likely to start later this year. The project will be carried out by Beliris, the federal agency charged with promoting the international image of Brussels, which is providing €16m in funding.

Pascal Smet, who launched the project in 2015 when a minister for the Brussels region (he resigned last year but remains a Brussels MP) says it is phase two of four. The first phase was the pedestrianisation of Chaussée d’Ixelles, and the current Toison d’Or phase will be followed by a reorganisation of the tram junction at Place Louise and a relook for the narrow mouth of Avenue Louise known as the Goulet (bottleneck).

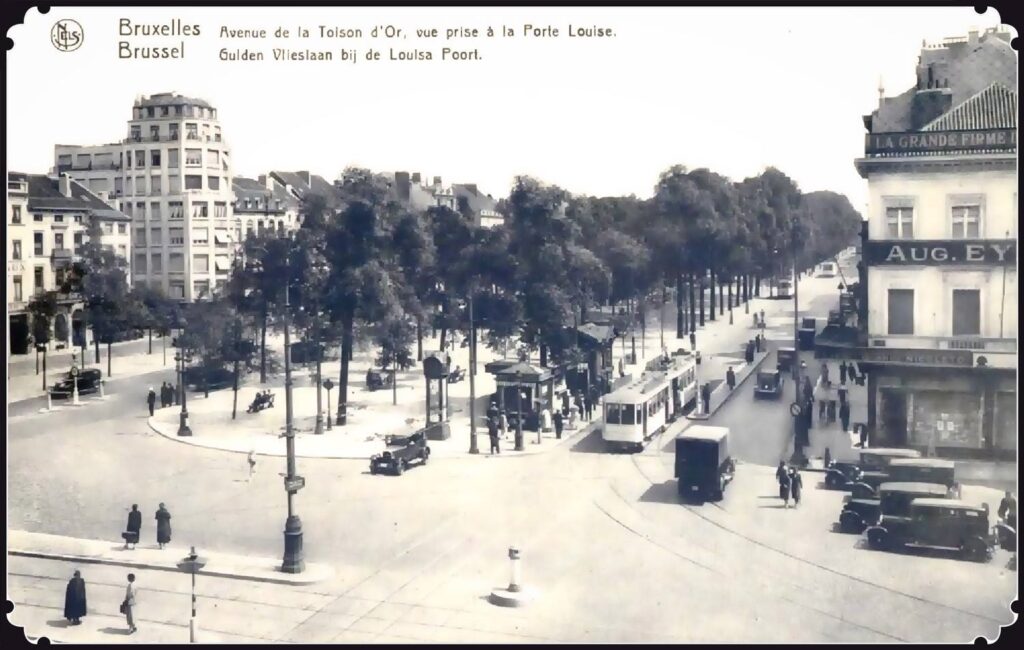

Porte Louise

Together, Smet hopes they will create a vast U-shaped open-air shopping mall where high-street brands will share a space with luxury outlets, in the hope that some of the latter’s prestige will rub off on everyone. A fifth phase could see the tunnels covered over, creating an immense traffic-free esplanade. Doing nothing to hinder that eventuality was a condition of the design competition for the Toison d’Or project, but there’s no money for dealing with tunnels at present.

The opponents of the official scheme, led by Interparking (which owns three car parks under the site totalling 1,250 spaces), criticise its ‘minerality’. They say such a broad expanse of paving material lacks not just greenery but a sense of architectural drama, which could be supplied by a large central structure. But are the alternative plan and the appeal a red herring, designed to extract concessions?

Smet told The Brussels Times Magazine that planting large trees with deep roots, such as the historic poplars, is impossible. Beneath the shell of the three roads are metro and road tunnels…and car parks.

He believes there is not enough private money at hand to fund the minimum €100m a partial cover for the tunnel would cost and that buildings mid-span would destroy the dramatic urban setting, definitively creating two streets and destroying its panoramic sweep. The revised plan, which includes the planting of more trees, but in metal cages to tame their roots, is ready to go, Smet says.

What’s in a name?

While the work will focus on a redistribution of public space from car to pedestrian, the authorities see this project as a tool to rebalance the fortunes of each side of the “emblematic” site. Boulevard de Waterloo and Avenue de la Toison d’Or should be “a symbol of luxury and prestige,” Smet says.

“These days, they look more like a vulgar motorway and a huge open-air car park than a promenade to encourage luxury shopping, strolling and relaxing. It's a crucial neighbourhood for the standing of Brussels,” Smet says. “The most expensive shops in Brussels are there, the luxury boutiques. But the place is not luxury: 70-80% of the place is devoted to the car, it's so 'old Brussels'.”

The 1970s when there were even more cars

As things stand, Boulevard de Waterloo is dominated by luxury shops with an international flavour (Tiffany’s, Louis Vuitton, Bulgari, Cartier, Balenciaga) and Avenue de la Toison d’Or by standard high-street brands (Zara, Flying Tiger, ICI Paris XL). Shoppers acquiring expensive accessories could glower at their counterparts munching Hector Chicken opposite if only they could see each other across a sea of traffic.

For the Brussels Region’s Bouwmeester, the office in charge of ensuring the quality of major architecture and urbanism projects, the two sides of the road are “disconnected from each other, not just by heavy traffic and parking but also by the commercial, hospitality and leisure divide between one side and the other”.

But why is the site so wide, what’s emblematic about it and how did this asymmetry arise?

Place names, even misleading and fanciful ones, can betray the origins of old urban neighbourhoods and reflect the age-old habit of reinventing them as aspirational addresses. Boulevard is one such evocative term, attached by myth-making planners to the least enticing edge-city locations. It shares its origin with the word bulwark and in this case, is justified. The footprint of the site planned for regeneration occupies one-sixteenth of the eight kilometres of defences that surrounded Brussels from the 14th century onwards. These gave the so-called ‘pentagon’ at the core of the Brussels City municipality its shape.

At the north-eastern end of the four-hectare site to be redeveloped is the so-called Porte de Namur, not an address in itself but a tag which commemorates the medieval gate which once stood here. The metro station and tunnel are named after it. The adjacent Square du Bastion meanwhile recalls in both name and pointed shape the thick, spiky overcoat of earthworks added to the exterior of the wall in the 16th and 17th centuries in response to the threat of invasion and evolving cannon technology.

1777 Ferrari's map of the area

At the south-western end of the site is the Place Louise, which was previously known as Porte Louise (the area was once marketed as the ‘Deux Portes’, a term that lingers on as the name of one of its three underground car parks). There was never a gate at Louise, rather a vast watch tower, known as the Grosse Tour, and its name is commemorated by a nearby street. A bulwark once connected the two ends, and the military term stuck when the wall was replaced by a street in the 1820s: Boulevard Waterloo was chosen for this, the section closest to the site of that battle.

The vast medieval gate impeding traffic between present-day Rue de Namur and Chaussée d’Ixelles was blown up in the 1780s when an order also came from the ruler of the Austrian Netherlands, Emperor Joseph II to remove the obsolete ring of defences encircling Brussels since the early-modern period.

In 1810, another emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte this time, ordered the demolition of the medieval wall itself. War and later the logistical challenge of dismantling (and auctioning off) such a vast volume of stone and brick delayed the work for years and the ramparts became a popular promenade for locals and visitors to peacetime Brussels. The views over the spires of the city and out into the countryside were described as the finest of any European city. An 1819 guidebook to the city claimed that the towers of the cathedrals of Mechelen and Antwerp could be made out on a clear day.

From city wall to boulevard

In 1819, French-trained architect and engineer Jean-Baptiste Vifquain won the competition to replace the city wall with a ring of elegant, tree-lined boulevards. Foreshadowing later urban transformations such as those of Haussmann in Paris (and Anspach in Brussels), it was assumed that rising land values along the new route would finance the cost of building the infrastructure.

The S.P.Q.B. (Senatus Populus Que Bruxellensis) plan bequeathed eastern Brussels a magnificent promenade that would be enjoyed for almost 150 years. It was however an 18th century solution to the urban challenges in a capital embarking upon industrialisation, and all this planted magnificence contained the seeds of its own destruction.

The execution during the 1820s was particularly inept along the section targeted by the latest renovation plan, helping to explain both the destruction of the 1950s and the lopsided development that is causing so much head-scratching today.

The neighbourhood now

Vifquain aimed to constrain Brussels within its centuries-old boundaries and mark a clear distinction between city and ‘countryside’, maintaining those forever views despite the growing lack of space in the former and the consequent risk of losing taxpayers to the latter. The plan exploited the breadth of the former defensive zone but ignored the bottlenecks for access to and from the city. A 75-metre expanse was created at a right angle to the main road into Brussels, Rue de Namur (itself barely 10 metres wide), prizing gyratory over radial mobility. It’s hardly surprising that car-focused planners in the 1950s would see a racetrack here.

When the work was complete, Boulevard de Waterloo emerged as a hem to Brussels as neat as those of the expensive dresses sold there today. By the 1830s an unbroken line of fine neoclassical mansions and townhouses hugged the city, home to aristocrats and upper middle-classes. The width of the road gave an abundance of light compared to more central districts, and wide, tree-lined allées offered excellent opportunities for exercise in clean air for horse and rider as well as fast communications back into the city and around it.

Opposite meanwhile, the-then Glacis de Waterloo remained rough and unfinished (a glacis is a slope aimed at making life difficult for soldiers attacking city ramparts). The budget hadn’t stretched to levelling the obsolete demi-lunes or ravelins looming above the Ixelles side.

The views from the remains of the bastions remained magnificent, however. In the 1820s, an English merchant called Swan built a country retreat on the high ground opposite the former site of the watch tower, and a Belgian painter later set up home on another bluff 200 metres up the road. Both houses sat behind the street line, divided from their elegant neighbours opposite by a fence marking the octroi, or customs border, a leftover from the ancien régime. Two neoclassical customs houses were built to replace the medieval gate, collecting taxes on goods moving between Brussels and its hinterland and getting in everyone’s way.

Rebooting the suburb

Levelling up the fortunes of the outer, Ixelles side of the road was going to require a marketing campaign and a regulatory gesture. In 1851, the glacis, by now known as Boulevard Extérieur du Régent, was given the snappier and more aspirational name of Toison d’Or, after the honour awarded to illustrious Belgians, in the hope that some of these would move there. In 1860, the octroi was abolished, and the already obsolete customs houses were replaced in 1866 by a splendid fountain commemorating the late Brussels mayor Charles de Brouckère (the customs houses now frame the entry to the Bois de la Cambre at the end of Avenue Louise).

Meanwhile, vast transformations downtown centred around the covering of the Senne prompted those who could afford it to escape the mayhem and the dust. Some of them finally set up home on the neglected glacis. An assortment of Belgian aristocrats and rentiers were soon joined by the American and Russian legations. By 1871, JR Scott, author of The Family Guide to Brussels reported that Avenue de la Toison d’Or was lined with, “large showy houses facing the Boulevards’ attracting ‘good English families.”

For a brief period at the end of the 19th century, the social prestige of the two sides of the road finally converged. Topography and mythology however would have the last word, literally undermining the existence of the new houses to the east.

In 1881, the owner of that Belgian painter’s house up on the bluff funded a new terrace to take advantage of the views from his garden by building a parade of shops below it alongside Avenue de la Toison d’Or (it is still there, host to a branch of Krefel). One of the first tenants was JR Scott, a serial entrepreneur for whom guidebooks were a side hustle to publicise his main activities as a house agent for British immigrants and importer of English ales. He was joined in the little gallery of shops by a baker, chocolate maker, tobacconist and two sisters selling office supplies. As the century wore on, commerce would exploit this first breach in the wall of residential properties. As it nibbled its way further south towards Place Louise, shop windows replaced respectable drawing rooms.

Meanwhile, up the road at Porte de Namur an entertainment zone had sprung up, with cafés, a theatre and later cinemas. An echo perhaps of a by then mythic period under the octroi when Brusseleirs in Sunday best headed for festive guingettes in the brewing suburb of Ixelles, where the beer tax was lower.

The tide of commerce

As Avenue de la Toison d’Or entered the 20th century, its residents began to depart. Unlike their longer-established neighbours on Boulevard de Waterloo opposite, whose houses boasted spacious stabling to the rear, their backyards dug into the remains of the ancient earthworks, blocking out the light and depriving them of room for stabling and, by now, parking.

One by one, these still-recent homes were absorbed by the fleshpots and attractions as they too crept south from Porte de Namur. In 1906, a rentier’s house at number 2 became the Altdeutsche Weinstube; by 1909, a widow’s home next door at number 3 offered tastings of Trappist beer (and has done ever since); and the following year Baron Chazal’s residence at number 4 was knocked together with number 5 to make way for the Select Cinema. A trickle became a flood and by the late 1920s, the Ixelles side of the street was given over to both the pleasure-seeking public and the means of transporting them there, with Baron de Mévius’ mansion occupied by the Brussels tram company offices and flanked by car dealerships.

Rue Capitaine Crespel, circa 1900.

Opposite meanwhile, Boulevard de Waterloo maintained a prestigious residential air for a further generation. The Princess of Arenberg, whose family owned many of the houses here, was still listed at number 16 just before the First World War. The Arenbergs, like the Altdeutsche Weinstube opposite, were gone by the 1920s, driven out by their German associations.

As noise from the growing number of cars finally persuaded others to follow, the street attracted a more genteel form of commerce, such as haute couture, antique dealers and flower shops. After all, in contrast to the brewing roots of its neighbour, the historic hinterland of this side of the road had been the luxury goods industry targeting the nearby royal palace. Two sleepy cafés, the Nemrod and the Waterloo, opened at the south end of the street, serving a legal clientele from the Palais de Justice behind and quite unlike the noisy drinking halls opposite.

This divergence between mass market and luxury commerce on each side of the street would continue to widen as cars occupied more and more of the vast span of the road in ever greater numbers. By the mid-1950s as the 1958 Expo approached, anything occupying more than a sliver of public space that didn’t serve the purpose of easing fast traffic was regarded as an obstacle.

The great poplars that had lined the avenue since the 1820s were felled and the Porte Louise tunnel was opened to the south. In 1957, the Brouckère Fountain, by now an informal parking spot anyway, was dismantled to ease the Porte de Namur bottleneck and in anticipation of another tunnel at the north end.

A group of students bearing a funeral wreath exhorting “prayers for our monuments” gathered to protest. On their coats, painted slogans read: “Too many civil servants, too many roadworks, too many taxes.” After saluting the nearby statue of Leopold II, they climbed over the hoardings surrounding the demolition site to place their tribute, and a student called on Brussels to look forward to the day when all the tunnels would be filled in.

Tunnels for drivers - and shoppers

In 1967, the Porte de Namur tunnel opened, sweeping away the entertainment zone that sat within the triangular imprint of a vanished bastion (present-day Square du Bastion preserves its shape). The same year saw the inauguration on Boulevard de Waterloo of the prestigious Hilton Hotel and the Brussels outlet of Yves Saint Laurent. Across the expressway meanwhile, Avenue de la Toison d’Or struck back in the 1960s. Lined by more down-to-earth brands along its entire length, it now tried to make a virtue of the obstacles that deprived it of the cachet enjoyed by its rival.

Two passages were burrowed at right angles deep into the remains of the ancient earthworks. The Galerie de la Toison d’Or obliterated what remained of two magnificent 1864 houses long since converted into a cinema (now the 14-screen UGC Toison d’Or multiplex). The Galerie Porte Louise meanwhile was dug under the former garden of Mr Swan, connecting the street with Avenue Louise. In 1970, a travel article for German newspaper Die Zeit, ‘Two Days in Brussels’ assured its readers that they should go there to find the young and trendy youth of Brussels, in the boutiques clustered around the Drugstore Louise: “Brussels has no Champs-Elysées. That's why Brussels has its elegant galleries…where Brussels chic shines.”

in 1971, when the trams ran alongside the cinema

That shine has since worn off. Much of the gallery leading to Avenue Louise is empty, Brussels still has no Champs-Elysées and Toison d’Or, now beset by a cost-of-living crisis, still trails in the wake of its rival. The old Nemrod and Waterloo cafes opposite the gallery are now Dior and Louis Vuitton, both crisis-proof for now at least. As things stand, big-spending visitors to those high-margin, low-volume boutiques along Boulevard de Waterloo enjoy unreconstructed kerbside access to the stores, a situation those traders would like to maintain.

Among the businesses reportedly most firmly opposed to the loss of parking were several of the luxury stores (but not The Hotel, the successor to the Hilton). However, the car-first set-up is virtually certain to go. Already in March 2023 a period-piece from the 1960s, the petrol station, closed for business after its operating permit expired, deemed incompatible with the upcoming changes.

Ever-resourceful, Brussels motorists have since used its still-standing carcass as extra parking, and proposals for an EV charging station came to nothing. Parking at the side of The Hotel will also be rethought. The aim is to lure pedestrians from the newly-paved esplanade into the idyllic Parc d’Egmont that sits behind The Hotel, plugging the boulevard into its own historic neighbourhood of the Rue aux Laines and Sablon.

Most shoppers opposite in the low-margin, high-volume stores lining Toison d’Or arrive at underground car parks or metro stops, then negotiate a cracked and patched pedestrianised zone from a previous era. The new chequered paving stones and caramel-tone bike lanes will sweep away another period piece with them: the four-metre-high Homme de l’Atlantide, or Man from Atlantis, a baffling 2003 bronze sculpture of a goggled aquanaut goes unnoticed by many (and many who do notice it regret doing so).

Along with its fountain and backpack, the artwork/roundabout will be removed like that of de Brouckère before it, destination unknown. The permit requires the region to consider a new piece of public art for the pedestrianised zone but nothing concrete (or bronze) is confirmed for now.

Back to the drawing board

Coaxing traders from the luxury end of the market means improving the all-round experience, according to the planners of the new scheme. While airport-style top brands are unlikely to land on the Ixelles side, the street needs to retain and attract mid-market names, like clothing store Arket which recently moved to Avenue Louise, to be replaced by budget alternative C&A.

Mock up of what the upgrade will look like

And that’s without counting the cost of maintaining shops in prominent locations such as Avenue de la Toison d’Or or the impact on trading of work that could last until the end of 2025 or beyond. As this article went to press, Krefel announced it was quitting its store in that quirky 1881 parade after just two years, blaming excessive rents and the forthcoming disruptions. Decorated inside and out with bespoke artwork, this outlet of the humdrum national chain had specifically targeted a largely car-less but solvent ‘urban’ clientèle from the prosperous inner suburbs, with an in-store café and delivery by cargo bike.

But further south into the region’s cosseted hinterland, it is clusters of boutiques in Uccle and destinations like the refurbished 60s cool of the Royal Belge complex in Watermael-Boitsfort that lure younger consumers seeking convenience and spectacle. While the Apple store is a bright spot for Toison d’Or, the curvaceous prize-winning Jaspers-Eyers building from 2015 that contains it is barely appreciable from the street among the clutter.

The new plan hopes to fix such issues. Firstly, by exploiting the virtue of the original 1820s design for the site – its extraordinary width – by sweeping away the eyesore of the parking lot, reuniting the street’s two sides and revealing a panorama to serve as a spectacle and destination in itself. Secondly, by correcting some of its vices, such as the bottlenecks shutting it off from its neighbourhood on the suburb side, creating a unified promenade from Chaussée d’Ixelles to place Stephanie at the end of the Goulet, around the ancient earthworks. And perhaps through them, if the galleries can be revived. As for the tunnels, they may never be filled in, but if the project delivers its promises of prosperity for the area, we might be able to put a lid on them one day.