Brexit notwithstanding, English remains the most spoken foreign language in the EU. For the last two decades, it has served as the 'lingua franca' of EU institutions as well as among non-native speakers.

Regardless of the UK's status in the bloc, the English language is here to stay. A 2012 Eurobarometer report found that English was the most widely spoken foreign language in the EU, with 38% of respondents being conversant at some level.

German is the language spoken by most native speakers (16% of the EU population), followed by Italian (13%), French (12%), then Spanish and Polish (both 8%).

Moreover, English is making gains across the bloc.

Brussels: Home of 'Euro English'

Euro English has become increasingly prominent, especially among EU civil servants in Brussels. This everyday, colloquial form of the language used by people working in the EU's institutions and frequently blends work-related jargon with British English. Direct translations from other languages are common and no one will pull you up on a preposition out of place.

German Greens MEP Terry Reintke told Euronews about her experiences with Euro English at the European Parliament: "It is a little bit of a messy use of English. It's people trying to express themselves but very often taking direct translations from their native languages and adding to that a kind of technocratic language that comes from the European institutions."

"In the meetings where we don't have interpretation and where people communicate in English, this is how we get our point across."

Language of diplomacy

Though the EU has 23 official languages, just three of them are seen as "working languages" employed in the European Commission – English, French and German.

In practice, Germany hasn't made a strong push for German to be used as a common language. By contrast, the French have insisted on promoting French.

During the French Council Presidency, France insisted on using French in the EU, much to the annoyance of particularly Nordic and Baltic EU civil servants who mostly speak English as a foreign language.

It wasn't always this way. French used to be the language of diplomacy but when Eastern European countries were accepted into the EU in 2004-2007, French lost its status in favour of English, as most of the new Eastern European Member States spoke English as a foreign language.

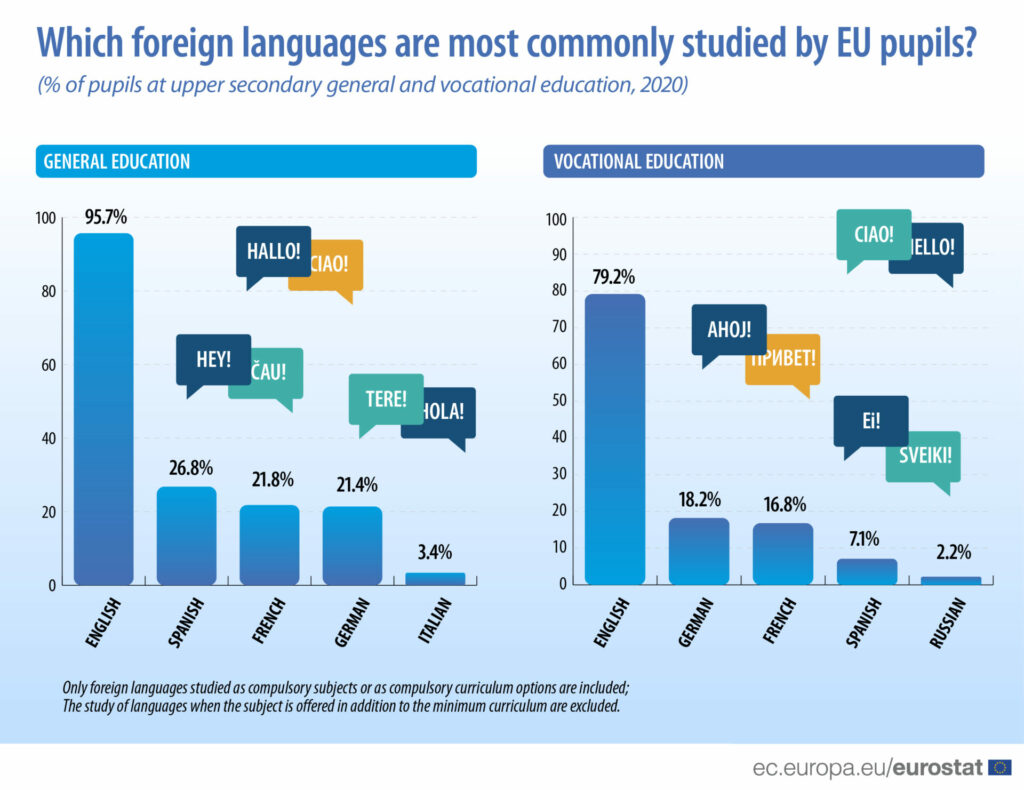

Foreign languages spoken in the EU. Credit: Eurostat

Now, most EU civil servants from smaller countries quickly switch to English, as it is a more efficient way to get their point across quickly and ensure their points are understood.

Yet English is now only an official language in two small Member States – Ireland and Malta, where it is the second language to Gaelic and Maltese respectively.

The people's language

Previous EU Affairs Minister Clément Beaune and Secretary of State Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne wrote in Le Figaro in 2021 that France's EU presidency was "an opportunity to hold high this vital fight for multilingualism."

They acknowledged that the use of French in the EU "had diminished to the benefit of English, and more often to Globish, that ersatz of the English language which narrows the scope of one’s thoughts, and restricts one’s ability to express him or herself more than it makes it easier."

But the EU can't force language upon people, even if it encourages citizens to be multilingual. Learning languages is ultimately up to Member States and according to a Eurostat survey in 2020, 96% of students opt for English as their first foreign language.

Related News

- Belgium in Brief: When is a Belgian not a Belgian?

- Where to learn French and Dutch as an adult in Belgium

With the UK now out of the EU, many view English as a more neutral language; trying to switch to another common language could lead to tensions.

"They (Europeans) probably see English as a European lingua franca, so I think that would be very hard to change both practically and in terms of the way that it's actually used," associate professor of linguistics Professor Heath Rose from Oxford University told Euronews.

"There could be ideological reasons to change this but then we would get into quite political hot water in terms of what language should replace it. In many ways [the UK having left the EU] takes the political argument out of it. If English is no longer the nominated language of any of its users, then it can kind of serve a more egalitarian role.”