Across the Brussels region, major postwar buildings are being restored and repurposed. This is mainly for environmental reasons, to avoid the wastefulness of the cycle of demolition and reconstruction. But it is also to strike a better balance between residential and office use in parts of the city zoned that way from the 1950s onwards.

In the heart of Brussels on Boulevard Anspach, work is underway to convert the former Grands Magasins de la Bourse department store into a multi-use structure featuring hospitality, shopping, co-working offices and 4 residential storeys. The site dates from the 1870s but was largely rebuilt after a disastrous fire in 1948 and the developer aims to retain 90% of the facade. In the 19th century base of the building the plan is for an outlet of Italian-themed eatery Eataly and a bar is planned high up beneath the eponymous dome.

The facade meanwhile will be partially reclad in the inescapable dull gold of 2020s Brussels, matching the accessories added to the Bourse opposite during renovations completed in 2023. East of the centre, autumn 2024 should see the winner named for a vast project to update Block 130, a 10,000 square metre, 1980s EU admin behemoth on Rue de la Loi for use as flats and shops as well as offices, as part of the reinvention of the EU Quarter. These plans are among those reflecting the crisis urban policy faces from changes to the climate and working practices, as well as a response to and encouragement of evolving attitudes to dense city living.

A third argument for retaining distressed postwar giants scattered across the capital is their potential as monuments, regardless of original purpose. Brightened up inside and out and thrown open to the public as homes, shops, restaurants or venues for a day out, they might help the city shake off the Brusselization slur, arise from its art-nouveau laurels and boast of an unbroken track record of excellence in architecture.

Charles Diongre's initial plans for the Flagey building did not include the now iconic tower

In mid-2023 the mammoth former Royal Belge insurance building in Watermael-Boitsfort (1967-70, architects René Stapels and Pierre Dufau) reopened in its magnificent setting in the Woluwe valley on the edge of the Sonian forest. Heritage protection saw off the threat of total demolition to make way for a new US embassy, and today the obsolete corporate headquarters hosts not just offices but a hotel and apartments. The homes aren’t cheap but anyone can enjoy a waterside drink or meal at the food market on the ground floor. Thanks to its location, smoked-glass seventies cool and lavish budget, the conversion, promoted by the region’s Bouwmeester (master architect) has been a success.

The Heritage Factory

In downtown Brussels, a far greater challenge for the authorities is the many large office buildings hammered into the cityscape in the wake of Expo 58 and rendered obsolete by corporate mergers, successive revolutions in the organisation of work and planning laws. Many are in the still-contentious, unfinished concrete style known as brutalism. The challenge is how to persuade a public accustomed to regarding these vast temples to bureaucracy and finance as eyesores and assassins of the city’s beauty that they are in fact valuable heritage that has been hiding in plain sight.

Which is where an exhibition at the Brussels Region’s Saint-Géry centre comes in. It removes such buildings from their geographical context, displaying them instead as discrete objects of design within a timeline of architecture in the city over the 20th century (and beyond).

The venue, whose own home is a repurposed covered market from 1882, calls itself The Heritage Factory. Its latest production line is called Archi BX 1900-2000, a chronological selection of 18 structures from across that period. This “architectural whirlwind” tracing “the unsettled path trodden by modernism” starts with a 1905 Flemish renaissance fantasy house in Ixelles recreating the 16th century inside and out for an eccentric city archivist and historian who wanted to take his work home with him. Passing through Art Nouveau and Art Deco towards modernism, functionalism and postmodernism, the show tracks the retreat of bricks and iron before glass and concrete, and the evolution of scale and plastic forms made possible by the new materials and improved engineering techniques.

The steeple of the Church of Saint John the Baptist in Molenbeek-Saint-Jean, Brussels.

Like the diagram of the March of Progress tracking the evolution of early simians to homo sapiens, the accompanying captions make an argument for decades of gain rather than loss, thanks for example to the gradual disappearance of “pointless ornamentation”. The organisers have chosen new mid-century poster children (you can literally buy posters to take home) to move Brussels on from self-proclaimed Capital of Art Nouveau to just the capital of great architecture. It’s an update to the family tree of the city’s buildings (where Art Deco begat modernism, which begat brutalism and so on) and suggests that retaining its ageing but more recent concrete generations is an aesthetic as well as an environmental urgency.

Freedom through concrete

A quarter way into the exhibition is an arresting Art Deco house built in 1927 in Jette for the poet Jef Mennekens. The Withhuis is a Gesamtkunstwerk, that is to say designed inside and out, by the architect Joseph Diongre. Archi BX 1900-2000 pins it within the timeline as typifying the moment when “concrete freed architecture” from the “straitjacket” of historic forms.

While its fussy, bespectacled facade is a mainstay of Art Deco guides to Brussels, Diongre himself is not well known. Most people however know his most famous building, the INR/NIR or Maison de la Radio/Radiohuis, built in the late 1930s as the headquarters of Belgian broadcasting. Now known popularly as Flagey, it has been a protected monument since 1994. With its warm, yellow brick façade and the helter-skelter tower overlooking the ponds of Ixelles, it was the first large modernist building in Brussels to win general public affection.

That affection was the key to its survival when, a decade after it was abandoned by broadcasters as too small and riddled with asbestos, demolition seemed the obvious solution. As at the Withuis, the interior of the Flagey building was also designed by Diongre, here in the paquebot or ocean liner style of its period. In 1998, the 60th anniversary of its inauguration, work started on repurposing the building as the mixed-use concert hall, cinema, cultural centre, TV studio and café we know today, retaining its principal facades and much of the inside.

The rejuvenated Flagey is a triumph of adaptation but perhaps doubly so, because its creator, 60 years old at the time of its completion, was at the culmination of his own journey of transformation.

Flagey at night

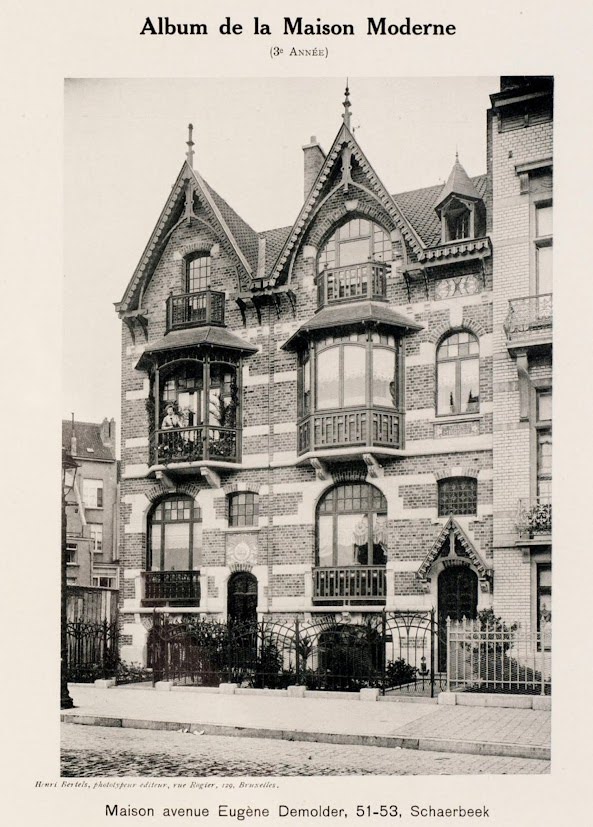

Born in 1878, Diongre had a conventional training, taught by and assisting established architects working in both the historicist revival of the 1890s and on the invention of Art Nouveau as a liberation from the narrow palette of established styles. Among his early works in the first years of the 20th century was a prize-winning Flemish neo-renaissance house and office for himself in Schaerbeek as a calling-card and which led to orders for houses in the same style across that rapidly-expanding suburb.

In his early years, he alternated that with polite and competent buildings in the Beaux-Arts and Art Nouveau styles. Nothing in their design set him apart from equally competent rivals, aside from a predilection for particularly orange-toned bricks picked up on a stay in the Netherlands, and nothing pointed to a future designer of Brussels’ best-loved example of sleek, large-scale modernism.

Diongre remained in Brussels during the destruction of Belgian cities and towns throughout the First World War and like many architects at home or exiled in London, the United States or the Netherlands he threw himself into the debate over the coming reconstruction of the country.

After peace returned, his output of rentier townhouses was immediately outweighed by his work on that reconstruction, including cités-jardins (garden cities) and other social housing around Brussels to improve desperately poor workers’ housing and provide decent homes for those arriving in a capital that had been spared destruction.

Working alongside peers such as Adolphe Puissant, Jean-Baptiste Dewin and François van Meulecom, Diongre designed tall rental blocks that filled in vacant zones between middle-class townhouses where expansion had been halted by war. On virgin sites at the edge of the region, natural greenery was preserved amid the low-rise housing of the garden cities, one of which bears Diongre’s name.

A new war of styles

There was a democratic as well as moral urgency underlying the reconstruction, with the elections of 1919 bringing de facto universal (male) suffrage. That same year, in the wake of the workers’ revolution in Germany, a law created a national low-cost housing company to channel loans to local housing associations.

The concept of reconstruction quickly widened out to cover improved services for the masses, both public and private, from clinics, schools, post offices and town halls to churches, banks and cinemas, and eventually radio stations. All required large new premises built at speed to a high enough standard to resist wear and tear from greater numbers, but cheap enough to justify public expenditure or provide sufficient returns to attract private investors. But in what style?

The traditional versus modern debate of the 1890s had not died with the war or with Art Nouveau. By the early 1920s, a key theme was whether the moral mission of the reconstruction, especially in housing, was compatible with new, foreign-influenced stylistic developments. Or should it accept the size constraints and additional costs of a Belgian vernacular, historicist style using traditional materials (nevertheless heavily influenced by a study of UK models, themselves perhaps inspired in turn by the low countries).

The Withuis, 183 Avenue Charles Woeste, Jette, by Charles Diongre

In January 1923, Diongre was named in an influential article among an intermediary generation of architects trained pre-war to deliver fussy, costly baubles aimed at the affluent but who were adapting to the challenge of using modern materials and techniques to build faster and bigger for an emerging mass consumer society.

Published in left-bank Paris journal l’Amour de l’Art, the article’s author Hippolyte Fierens-Gevaert was a Brussels-born opera singer-turned-journalist who had made his name writing about the arts in the French capital. An expert in Flemish renaissance art himself and the recently-installed inaugural head conservateur of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels, he used this position along with his cultural firepower as one with the ear of Paris salons to apply a wrecking-ball to Belgian architectural conservatism.

In his extraordinary panorama of the emerging modern movement, Fierens-Gevaert complains that in what had been a “land of architectural renewal” at the dawn of Art Nouveau in 1890, historicist backsliding among politicians threatened the success of reconstruction. In Leuven for example, a thousand houses destroyed during the invasion of 1914 were replaced by “grotesque imitations of Brabantine baroque or the 18th century”. In rural areas devastated by the German advance, rebuilding as “replica, regionalist pastiche was decreed in the name of the most revolting sentimentalism” by the kind of elected officials who regarded an innovator such as Victor Horta as a “corruptor of the young.”

Praising the modernist creations of an entire generation of Belgian architects and ignoring the conventional (and sentimental) output they still partly relied on for patronage, Fierens-Gevaert urges them to embrace the challenges of reconstruction and let necessity rather than desire direct design: “the saviour of architecture is destitution. Financial penury, standardisation, new technical methods can bring back simplicity, rhythm, unity. The reawakening of the classical rules!” No doubt aimed at shaming both architects and their clients, public or private, into action in the cause of national pride under the gaze of Paris, his piece was picked up by Le Soir. Architectural journal La Cité purred: “What could be more surprising than to see Paris paying homage to our modernists, whom we still prefer over here to hide under a bushel?”

Prize of simplicity

Who knows if patriotic pride spurred Belgian modernist architecture in the 1920s? The strictures of the reconstruction, with its emphasis on utility for the masses and value for money through simplicity, gradually came to dominate the creative thrust of the profession. As the decade wore on, the internationalisation of architecture, both stylistically and technologically, drove change.

Digging a grave for historicism, the 1925 Paris Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs would give its name to the embryo modernism known now as Art Deco. Architects like Diongre who had trained to serve a rapidly vanishing world (“mature men who understood the prize of simplicity” in the words of Fierens-Gevaert) would adapt, becoming undertakers to the 19th century and midwives to the modernism of the 20th.

For Joseph Diongre, that “unsettled path trodden by modernism” was marked in Brussels by workers’ housing, where he alternated between a rather brutal art deco and bucolic regionalism. In 1922, he designed roughcast cliff-like art deco apartments copied and pasted along the sunless Rue Gisbert Combaz in Saint-Gilles at numbers 10-14.

Diongre used a similar aesthetic in the northern suburb of Laeken, annexed in 1921 by the City of Brussels to give it more breathing space. Here, more generous greenfield sites allowed the architecture to be softened by planted front yards and the presence of fewer storeys but the continuous building line maintained their urban character.

30-32 Rue Charles Ramaekers, Laeken.

In 1923, construction started in Molenbeek Saint-Jean on the rather anti-urban Cité Diongre, where plaster and wood-clad cottages of various sizes and designs sit in an artful jumble between hedges and pocket gardens. A pair of much larger houses, in the same style but aimed at the bourgeoisie would follow in 1924 at rue Vanderkindere 258-262 in Uccle. Betraying perhaps his own tastes, Diongre would live in both of these houses over the next decade and a half.

The real break with the past appears to have been come in 1927 with the poet’s Withuis and for workers the Cour Saint Lazare in Molenbeek, where for economy’s sake, tiered walkways lined with flat metal panels take the place of conventional stone and brick as the principal facade, curving around the corner site in a manner pointing the way to the Flagey building, begun in 1935.

The rise of large public orders with strict budgets would shape Diongre’s architectural journey over the interwar period. These obliged him to adapt interiors to receive bigger numbers and house the services aimed at them as well as honing exteriors around these new volumes. At the 1932 church of Saint John the Baptist, Diongre used parabolic arches in reinforced concrete, technology created for factories and airship hangars, to create a nave with a vast span for a parish with a large flock of worshippers but no money (Molenbeek commune funded the project). The plastic possibilities of concrete (this was just the second Brussels church to be built in the material) allowed him to emboss the facade with a vast cross rising to the full height of the building to house the entrance bay. A spiritual variant on the concept of form following function, the modernist architect Huib Hoste described the result as “functional on the inside, expressionist on the outside”.

Inside the Church of Saint John the Baptist in Molenbeek-Saint-Jean, Brussels.

The first major architectural competition won by Diongre was for a new town hall for the commune of Woluwe-Saint-Lambert in 1909. Delayed by financial reasons and by the First World War, it would be the last of his major projects to be executed, just before a new world war, in 1938. Over the decades between Diongre’s first design and the definitive version, the population of Woluwe-Saint-Lambert had ballooned and a comparison between the two designs is an expression of his career arc in miniature. A project that started as a neo-renaissance faux-château serving a population the size of a large village became a sprawling modernist complex, incorporating features from his most arresting designs in the interim: the chiselled tower of Saint John the Baptist and the sleek yellow-brick curves of the Flagey building.

Serendipity

Diongre’s initial design for Flagey did not include a tower. The building’s most striking detail, the telescopic landmark rising above the square, drawing the eye to the building among not dissimilar neighbours, perhaps saved it from demolition decades later. The plan was adapted at the instance of a foresighted broadcasting engineer in anticipation of the advent of TV.

That his most celebrated creation was the result of happenstance and technological requirements underlies Diongre’s career among those who helped give birth to modernism, sparked by the reconstruction of the 1920s. Neither journeyman nor genius, the world he helped shape was in response to need rather than arbitrary desire, with form following function in as pretty a way as possible.

Place Flagey from the air in the early 20th century

A century on from Fieren-Gevaerts’ polemic, Brussels faces a new reconstruction to adjust the city to the needs of new generations, new revolutions in technology and perhaps most importantly, the challenge of climate change.

Unless there’s more backsliding, the proposed update to the planning rulebook for Brussels, the Règlement Régional d’Urbanisme/gewestelijke stedenbouwkundige verordening – RRU/GSV (known of late as ‘Good Living’, but that name is likely to change) will enshrine reconstruction and repurposing instead of demolition as the default solution for large buildings at the end of their lifespan. With cement production the largest single industrial emitter of greenhouse gases at around 8% of the global total, the vast postwar concrete structures already in place in the city will have to stay.

Like Diongre’s generation, architects addressing major sites must adapt, no longer rebuilding from scratch but reskinning and remodelling existing buildings, extending them outwards and upwards. This time, the reconstruction won’t be from the ashes of centuries gone but from the skeleton of the postwar boom.

Adapt or cry

It’s already happening by itself as, once again, the industry senses the political weather on the horizon. In 2014, BNP Paribas Fortis chose total demolition-reconstruction for its vast HQ in central Brussels. A decade on and the same bank is adapting the interior and restoring the exterior of the uncompromising cellular concrete lattice of the 1968 CGER building on Rue du Marais, now called The Hive and one of the stars of the Archi BX 1900-2000 exhibition.

Woluwe-Saint-Lambert municipal hall. Credit: Visit Brussels / Jean-Paul Remy

Two other vast brutalist offices in central Brussels by the same architect, Marcel Lambrichs, the former Crédit Communal on boulevard Pachéco and the former HQ of the Belgian Construction Federation on Rue du Lombard are being converted for use by universities. They are all safe for a generation or two and at Saint-Géry, Brussels wants you to learn to live with them, perhaps love them a little, as part of a repurposing and reconstruction of public taste. At the end of August 2024, hundreds of concrete postwar buildings were added to the region’s heritage inventory, including those listed above and Block 130 in Rue de la Loi.

Shake a fist at the ugliness that isn't going away. Or, like Diongre a century ago, adapt to the realities of the age, enjoy the exhibition and buy a brutalist postcard. They are recyclable.