If politics is showbusiness for ugly people, no one told Georges-Louis Bouchez. Arriving at the terrace of Café Belga in Place Flagey, he is dashing and debonair. He sports a plain, white t-shirt under a suit jacket (with a small Belgian flag pin on his lapel), his leather bracelets and tattoos peeking beneath his sleeve, and white trainers. His full, shoulder-length hair could see him cast in a shampoo commercial, but whatever his grooming products, the 37-year-old has allowed grey sprouts in his beard.

Bouchez, who has been the leader of the francophone liberal party, the Reformist Movement (MR) since 2019, is immediately keen to make a connection. He seizes on my English roots to express his love of all things British, from racing driver Lewis Hamilton to the Beatles, football and our sense of humour (although he goes too far when he extends his praise to British food). He even offers to do the interview in English, noting with a smirk, “My English is better than my Flemish.” We stick with French.

Bouchez’s Dutch language skills are notoriously poor, but far from being embarrassed, he turns it into a political point, blaming the education authorities in his native Wallonia for not making Flemish teaching compulsory. And it has not prevented him from touring Flanders, whether it is television studios, commemorative events or even on his holidays. “In opinion polls, I am one of the top-ranked French speakers in Flanders,” he says proudly, before ordering an orange juice.

Bouchez, sometimes known as GLB, is certainly one of the most visible. While his MR is part of the seven-party coalition under Prime Minister Alexander De Croo of the Flemish liberal Open VLD, Bouchez did not take a ministerial role, freeing him up to speak and tweet more, which he does. A lot.

He is charming too. Even critics admit that he is precocious, charismatic, dynamic and engaging. But they also say he is compulsive, needy and shallow. And a magnet for controversy.

Bouchez is more than willing to take it on his finely chiselled chin. “I know that my style is controversial,” he says. “I also know that my style can help bring in people who are not interested in politics. Some people say it's not the way to behave, but at least they can see that I'm authentic. Life in politics is already very complicated. If on top of that, you can't even live like you want to live, then forget it.”

Bouchez holds forth

A huge Formula 1 fan, Bouchez loves visiting Grand Prix circuits and even taking a spin on them. This, he says, is not what a calculating politician should admit. “In politics, normally, you have to be modest, especially in Belgium. Even a little miserable,” he says. “But I don't care. And if one day the paparazzi take a picture of me on a circuit, I'm not going to have to justify myself for a thousand years. I have a nice watch and I have a nice car, yes, so what? Where is the problem?”

Thatcher’s child

Bouchez’s did not come from a background of fast cars and fancy watches. He grew up in Colfontaine, between Mons and the French border. It is the third poorest municipality in Belgium, with one of the highest unemployment rates. His parents were small traders. “I have a bit of the spirit of Margaret Thatcher because of them,” he says. Bouchez says that watching his father struggle through a series of different jobs helped shape his relationship with work.

He describes his childhood as loving but deprived. “We had a fairly dull life,” he says. “I came from an environment where, when you arrived at school, everyone would talk about their vacation. But I never went on vacation.”

The young Bouchez would read and fill folders with newspaper cuttings. “I knew more about current affairs than a kid my age would normally,” he says.

Although he looks flamboyant and unconventional, in other ways, Bouchez is a goody-two-shoes. “I've always been pretty rule-abiding,” he says. “I was a good student, I went to class, and did the work. I've never drunk, never smoked. I don’t drink tea or coffee. You're not rebellious because you do drugs, you're not rebellious because you drink like crazy.”

He is often seen in the pit lanes at Formula 1 circuits

For him, being a rebel is about standing up for what you believe. At school, he would argue fervently with his history teacher on issues. “I would debate with him on the war in Iraq – he was against the intervention, I was for it – and we had debates throughout the year until he would say, ‘We have to stop because I have to teach,’” he says.

After school, Bouchez studied law at the Saint-Louis University, Brussels, followed by a master’s degree at the Free University of Brussels (ULB). At just 23, he started work in the office of MR heavyweight Didier Reynders, then Finance Minister and is now an EU Commissioner. He was first elected to office in 2012 at the age of 26, as a council member for the city of Mons, where he still lives, and two years later he was elected to the Walloon parliament.

He says 2016 was his political turning point when he was kicked out of the Mons council by the mayor and former Prime Minister Elio Di Rupo. It made his name. “People asked, ‘Who is this guy that Di Rupo is attacking?’ I was playing in the Third Division and went directly to the First Division,” he says.

After steadily raising his profile, he was named the MR’s spokesperson for the 2019 elections, when he won a seat in the Senate. Then, when the MR’s Charles Michel, then Prime Minister, was appointed President of the European Council, a vacancy opened at the head of the party. Bouchez stepped forward, beating four more seasoned candidates for the job.

With former Prime Minister Charles Michel

Shortly after becoming MR leader, Bouchez was named as one of King Philippe’s ‘informateurs’ to help research possible coalition options. When the government was formed, Bouchez succeeded in getting two MR deputy prime ministers and two other ministers in the cabinet.

Amongst the MR’s achievements in the government, he takes credit for the decision to extend the life of Belgium’s nuclear power stations. “I was the only one to defend nuclear power at the start,” he says. And he mentions the MR’s appointment of former news anchor Hadja Lahbib, whose family has Algerian origins, as Belgium's Foreign Affairs Minister, which he hails a step forward for diversity. “It is more than the appointment of a person; it is a political message.”

Desert fiasco

However, his political messages can get lost when his personal exploits suck up the attention. Bouchez relishes media opportunities, which can seem to be more about polishing his brand.

The stunts don’t always work out as planned and Bouchez was found wanting in two high-profile televised events. The first, in 2021, was a one-on-one contest with Antwerp mayor and N-VA leader Bart de Wever, who beat the younger Bouchez over seven disciplines, including running, rowing and weightlifting. Bouchez insists that he won six of the seven rounds, but it was the bike, the last test, that sank him, when complacency set in.

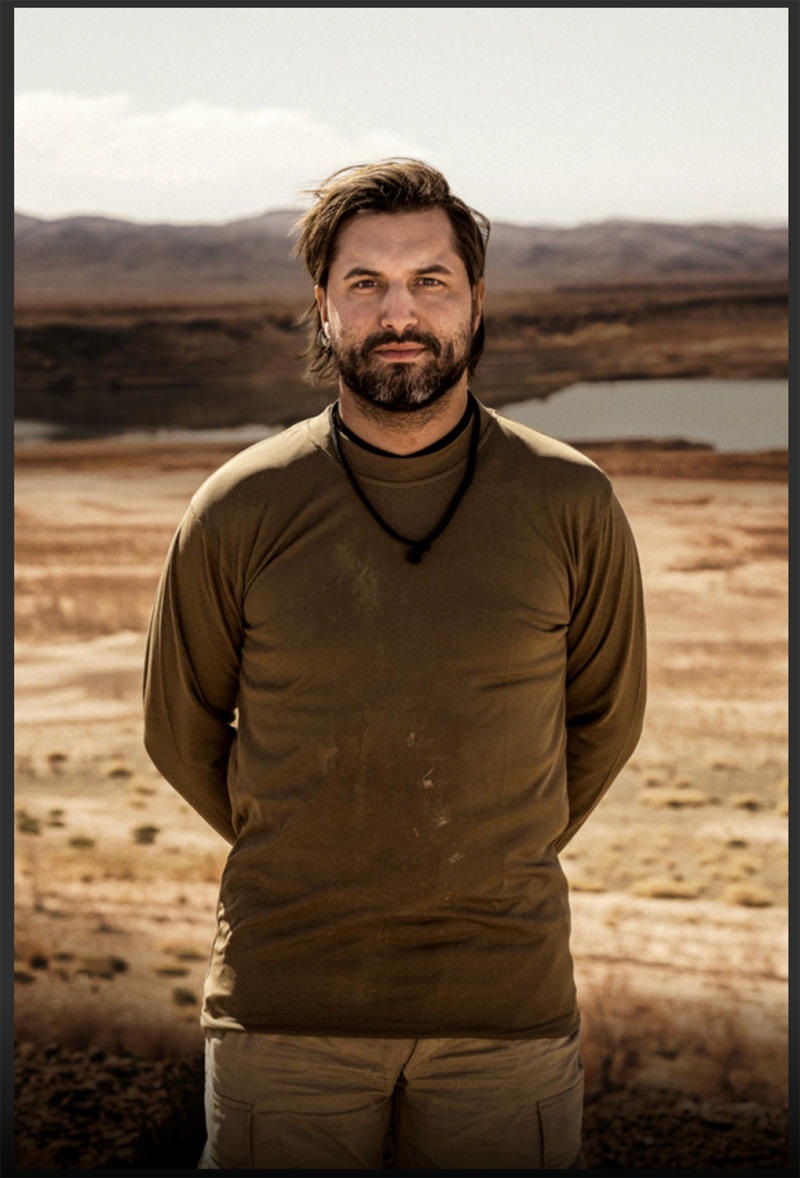

More recently, in May, he took part in a Flemish reality TV show, Special Forces: Who Dares Wins, a six-day training course in the Moroccan desert to join the Belgian army's elite unit. However, he quit after the second episode, following a lacklustre performance – and scathing criticism from fellow contestants for being “lazy” and “a dead weight”.

Bouchez's infamous appearance on the TV show, Special Forces: Who Dares Wins

It was not the first time a Belgian politician has indulged in light entertainment on TV: Flemish socialist leader Conner Rousseau notably wore a rabbit costume for The Masked Singer. But some saw Bouchez as going too far – and his image as a man of action took a knock when he flamed out. Instead, he became a figure of ridicule, notably when he was seen hanging upside-down from a metal bar, and being told by a trainer, “Colle ton zizi à la barre!” (“Stick your dick to the bar!”).

Yet, again, Bouchez is unapologetic. “I don’t regret anything, it's pointless,” he says. “It's true that with hindsight, I should have trained – that's obvious. But it took on crazy proportions and the media treated it as something really serious.”

He says he just wanted to enjoy a boyish challenge. “I was told I could go train with special forces in the desert in Morocco. So I thought, ‘Wow, cool, I’ve never seen that before. And I'm still going to meet people and then I'm going to have fun,’” he says. “I still have the same state of mind as when I was 20. I feel I’ve stopped ageing - I mean in my head, I kept the same mentality.”

That explains his football obsession. He is chairman of Royal Francs Borains, a club in Belgium’s second tier and regularly goes to see other Belgian clubs in action.

Bouchez is the president of Royal Francs Borains football club

It also explains his tattoos. He has three big ones on his arm: a Road Runner cartoon (because his mother always said he was as speedy); an Apache warrior (he identifies with the hold-out tribe); and a Samourai warrior (to reflect their sense of honour, he says).

The GLB philosophy

With an eye on next June’s Belgian elections, Bouchez is trying to lay down some more serious philosophic credentials, and in August, he worked with former RTBF journalist Alain van den Abeele on a book, À bâtons rompus.

The book, he says, explains his political philosophy, including his belief in a positive work ethic. In Wallonia, he says the PS has created a benefits culture that disincentivises people from working. Bouchez gives as an example the difficulties Wallonia’s public bus service has in recruiting 300 new bus drivers. “You're not going to tell me that there aren't people out there who can drive a bus?” he says. “How is it that we're one of the countries in Europe with the biggest job vacancies, jobs for which no one seems ready to do, and yet we have so many unemployed? It doesn't make sense.”

When it comes to the eternal Belgian challenge of reconciling the French and Flemish speakers, Bouchez shrugs. “I think that it works the political class up much more than people,” he says.

But if most Flemish voters back parties that explicitly want to break away, surely that’s a problem for Belgium? “Yes, but the people who vote for the Socialist Party (PS) don't vote for a class struggle. However, the first article of the Socialist Party is that we live in a world where classes fight against each other,” he says.

He says extremist parties – the far-right Vlaams Belang (VB) nationalists and the radical left Workers' Party of Belgium (PTB/PVDA) – succeed because voters are disillusioned. “People tell me, ‘We'll try VB because we tried all the others and it didn't work.’ But that doesn’t mean they want to split Belgium,” he says.

Bouchez is ready to engage – in French, of course – with his Flemish counterparts. Last year, he debated on television with VB leader Tom Van Grieken, breaking a pact by mainstream parties for a cordon sanitaire around the extremists. He defends the debate. “It’s absurd to have media cordon sanitaire around a party which has 25 percent of the vote,” he says. “They already have more votes than the others - and in addition, you prevent them from being attacked.”

Knocked in Knokke

But Bouchez himself can sometimes be a lightning rod for Flemish anger. In June, passers-by filmed him in an altercation in the coastal town of Knokke. Getting out of his car to speak to what he says were aggressive cyclists, he is seen being shoved in the chest. While he did not push back, his girlfriend is heard shouting, “Sale Flamand!” or “Dirty Flemish!" – a comment that Bouchez claims was a response to “Sale Wallon!” jibes.

Bouchez says the pushing incident was not political, and he does not think he was recognised by the man who pushed him. Still, it was politicised: young members of the hardline Flemish N-VA party printed t-shirts with “Sale Flamand” and presented one to Bouchez (he characteristically posed cheerfully in a photo with them).

It should be noted that the Flemish are not the only ones to have physically attack Bouchez: a man shoved a pie in his face at an event in Liège in October.

Hit with a custard pie

Bouchez argues that nationalist populism, like that of VB and the N-VA, needs to be tackled at source, which means making the middle classes feel represented in the political landscape. “There is an over-representation of certain categories of the population, of a whole series of minorities,” he says. “I'm not saying that they shouldn't be represented. I'm saying that certain themes are over-represented. It’s this that creates populism.”

He blames mainstream parties for misleading voters. “What kills politics is when you say things that you know don't correspond to reality,” he says. He accuses them of denying the downsides of immigration and trying to close down the debate about the real challenges for communities. “By labelling all those who talk about immigration racists…well, now the extreme right is everywhere today because people say, ‘They’re telling stories. I can see in my street that it’s not like that,’” he says.

This kind of discourse generates populist accusations against Bouchez himself. He did not help his case when, for example, he praised French extreme-right politician Eric Zemmour. Justice Minister Vincent Van Quickenborne, whose liberal Open VLD party is nominally an MR sister party, has been particularly critical of Bouchez, describing his stance as "more conservative than liberal,” and his grandstanding style as "He barks while we act.”

Bouchez accepts that while MR is a liberal party on social issues, it takes a more classically conservative stance on economics. He says it is somewhere between the Conservatives and the Liberals in the UK, or the politics of French President Emmanuel Macron, one of his political heroes.

Values or rent

However, much of his political messaging is about how most mainstream politicians are too fixated on values. Bouchez recounts a recent meeting of Europe’s umbrella liberal group, ALDE, which includes MR and Macron’s party, Renaissance. “I have colleagues who say, ‘Ah, the values of liberalism are so important and we have to fight against fascists and for LGBT rights.’ And at the last meeting, I took the floor and said that values are great but they don't pay the rent, and people today want to know how they pay their rent and how they pay the children's school tomorrow.”

This plays into another of Bouchez’s themes, which is about what he sees as the dangers of wokeism. He doesn’t define the term, but he rails against it, and both the left and greens in general. “I don’t like people who lecture others, like American actors who spend the whole summer on a yacht and then they go to the United Nations saying you have to save the climate,” he says. “The left tries to make believe that it is the rich who pollute, it is not true. It's terrible what I'm going to say, but what pollutes is that today is mass consumption: we have allowed poor people like me to consume.”

At an MR event in Durbuy, which included a zipline ride

At this point, Bouchez turns his gaze around the Café Belga and decides that its clientele overlaps with the vague woke community – although he uses an older French term, bobo, which means bourgeois-bohemian, roughly equivalent to Champagne socialist. “It's not my basic café, I can tell you that,” he says, chuckling. “It's really bobo style to death. That is, they live in a big city, they take their electric scooter to go to a Starbucks to use their Mac laptop to post on Facebook that capitalism is shit.”

Likewise, he takes an unprompted pop at young climate demonstrators. “They’re not the young people from places like Genappe and all these working-class towns. I know them. These young people, they want to live like Karim Benzema. The climate is not their main concern,” he says. “It’s when you're in a more privileged environment that you can start saying to yourself, ‘Oh, the climate is important!’ and you can say you’ll cut your living standards because you've already travelled and you already have a nice house. But when you have nothing, or very little, what are you going to reduce?”

The party of motorists

This raises one of the criticisms of his party, that in Brussels, a city struggling to address its chronic congestion, the MR is seen as an infallible ally of motorists. “We're not anti-cars, that's true,” he says, defending driving as a free choice. “Humans are rational beings and therefore they will always choose the means of transport which is the most effective for them.”

He does, however, admit that other means of transport should be improved, and notes that it has been years since any new metro track was laid down. “We have not developed public transport networks, but alongside that, we are making driving more complicated. But people continue to take their car since they have no alternative. So what does it do? It creates more traffic jams and more pollution,” he says.

He even calls for fewer rules for motorists, for example, with no-entry streets opened at night, when there is less traffic and flexible speed limits. “The tunnels have a 50km/hour speed limit – but at two o'clock in the morning on weekdays, if they are 70km/hour, what’s the problem?” he says.

But for all his gripes about his compatriots, he is quick to show his pride. “We are a country that has the best of the Latin worlds, the Germanic worlds and the Anglo-Saxon worlds. We are at the crossroads of all worlds,” he says, listing infrastructure, universities, human talent and a particular sense of identity as Belgium’s key assets.

“Belgium is an extraordinary country whose inhabitants are the least aware of its extraordinary character,” he says. “I will not live in another country, that's clear. I’m very, very proud and I would like us to have more pride because we have lost that pride and we have to find it again.”