Fortuitous coincidences can have long-term repercussions. This is the case for the collision, in July 1952, between two largely independent strings of events. The central character in this collision is Belgium’s King Leopold III, its main lasting outcome the European Parliament’s “travelling circus” between Brussels and Strasbourg.

Philosopher Philippe Van Parijs reflects on current debates in Brussels, Belgium and Europe

A fatal night

Why is the European Parliament stuck with a dysfunctional arrangement that forces it to hold its plenaries in Strasbourg, run part of is secretariat in Luxembourg and conduct most of its activities in Brussels? Because of something that happened in Paris over seventy years ago, in the early hours of July 1952. The ghost in the room, the unwitting cause of this fatal decision, was Belgium’s King Leopold III.

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) had been created by the Treaty of Paris on 18 April 1951 and was supposed to start its work on 1 August 1952, with Jean Monnet chairing its executive. But where? The foreign ministers of the six member states gathered in Paris on 24 July 1952, together with Monnet, in order to give to this question a definitive and urgent answer.

The Netherlands proposed Brussels, with the support of Germany and Luxembourg. But late in the night of 24 to 25 July 1952, one person expressed his total opposition to that option: Paul van Zeeland, Belgium’s foreign minister.

In his Mémoires, Jean Monnet evokes this crucial moment as follows: “Amidst the confusion, I remember van Zeeland saying something that speaks volumes: "It's late, we're all tired, so I shall speak frankly…” Brussels was suggested, but he opposed it: for electoral reasons, as his mandate was limited to Liège." According to another testimony, van Zeeland even said: “If I accept Brussels, my government will be toppled tomorrow.”

Direct democracy: referendum and riots

To understand the Belgian veto, it is necessary to go back a few years to what happened during World War II. After the capitulation of the Belgian army in May 1940, King Leopold III did not follow the Belgian government to London but chose to remain in his palace in Laeken as a prisoner of the Germans before being transferred to Germany towards the end of the war.

Many in Belgium disapproved this choice and opposed the King’s return to Belgium after the war ended. The King then proposed that the question of his return be subjected to a national referendum.

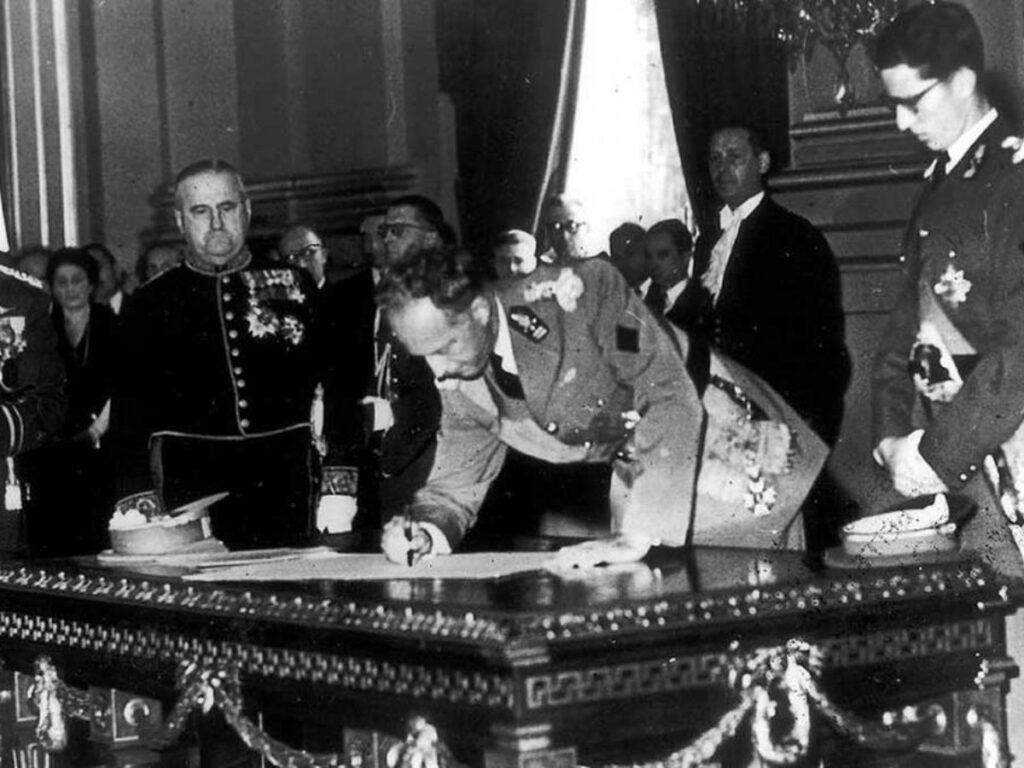

The right-of-centre Christian-Liberal coalition government acquiesced and a referendum — the only one so far in the history of Belgium — took place on 12 March 1950, in an extremely polarized context.

The more industrialized — and therefore more socialist and more Walloon — parts of the country voted against the King’s return, the less industrialized — and therefore more Christian and more Flemish — voted in favour. The net result was a 58% majority in favour overall, but also a 58% majority against in Wallonia, due to a strong majority against in the most industrialized and densely populated provinces of Liège and Hainaut.

The outcome of the referendum did not settle the matter. It exacerbated the tensions. Capitalizing on the salience of the issue, the Christian party obtained an absolute majority three months later at the national elections on 4 June 1950 and could form a single-party government — the only time this has ever happened since Belgium switched to proportional representation in 1899 and, it can safely be said, the only time it will ever happen.

The King returned to Belgium on 22 July 1950 at the invitation of the government. His return triggered riots in Wallonia. And on 30 July, four demonstrators were killed by the riot police in a suburb of Liège.

Two days later, the King abdicated in favour of his 19-year old son. King Baudouin took the oath before Parliament on 16 July 1951. While he was speaking, a communist member of parliament from Liège shouted “Vive la République!”. He was assassinated one month later.

No to Liège, yes to Luxembourg.

In this exceedingly turbulent, sometimes insurrectionary context, Belgian citizens and politicians may be forgiven for paying little attention to the inaugural act of European integration, the Schuman Declaration of 9 May 1950, squeezed between the referendum and the Christian party’s electoral landslide, and even less to the signing of the ECSC Treaty on 17 April 1951, stuck between Leopold’s abdication and his son’s accession to the throne.

So, when the time came to reach a final decision on the seat of the ECSC, at the meeting of 24 July 1952 mentioned earlier, the Belgian government was above all driven, as Monnet put it, by “electoral reasons”, namely by how badly the Christian party would fare at the next elections in Wallonia, in particular in Liège.

This was of special importance to the minister of foreign trade, in charge of the ECSC negotiations, Joseph Meurice, a Liégeois and active member of Le Grand Liège, a lobby that argued that Wallonia’s largest city, at the heart of Belgium’s coal and steel industry, was the ideal choice for the headquarters of the ECSC.

Alas for Liège, none of the other member states shared that view. And in the very early hours of 25 July 1952, Joseph Bech, prime minister of Luxembourg, reluctantly agreed to host the ECSC headquarters in his capital. On 10 August 1952, the ECSC’s executive started working in the former premises of the Luxembourg Railway Company. But what about its assembly? With no university at that time, Luxembourg had no suitable auditorium in which the assembly could meet, albeit provisionally.

Traveling circus

Strasbourg came to the rescue. Not too far from Luxembourg and since 1949 the seat of the Council of Europe. The first time the Council’s assembly met, on 10 August 1949, with Paul-Henri Spaak (later to become the mastermind of the Treaty of Rome) as its chairman, it did so in the aula of the University of Strasbourg.

From the following year, it met in a purpose-built provisional Maison de l’Europe and from 1977 in the definitive Palais de l’Europe. The Council of Europe was happy to share these premises with the ECSC assembly, that grew into a directly elected European Parliament in 1979, until the latter moved to its exclusive premises, the Louise-Weiss building, in 1999.

Over the years, the European Parliament gradually expanded its activities in Brussels, with an estimated two thirds currently taking place there, in order to be closer to the executive it is meant to control and to the many other EU-wide organizations present there.

A majority of its members has also repeatedly expressed a wish to put an end to the huge environmental, financial and time cost of the “travelling circus” used by Brexiteers as the paramount example of EU absurdity. Yet local vested interests are understandably strong and, as former Commission President Jacques Delors once told me: “Of course, this situation is absurd. But France will only give it up when it will feel sufficiently strong.”

Had Brussels been chosen in July 1952, despite Belgium’s insistence on Liège in the aftermath of Leopold III’s failed return, all of this could have been avoided. The University of Brussels would no doubt have gladly hosted the ECSC’s assembly meetings until appropriate premises had been built. And the choice of Brussels six years later for the executives of the newly created European Economic Community would have been obvious and deliberate instead of fortuitous.