With Mobility Week culminating in Car Free Sunday, the question of how Brussels moves is centre stage. And whilst there are many ways to get around the city, this topic is frequently reduced to a contest between cars and bicycles – a framing that isn't always constructive.

How can Brussels reduce traffic to become an easier space to navigate? How can it cut pollution and improve the general well-being of residents? If bicycles play a big part in answering these questions, how can it become a better city for cyclists?

To outline the challenges and propose solutions, the Group for Research and Action for Everyday Cyclists (GRACQ) offers expertise in this domain. Over the past 50 years, the organisation has developed a detailed understanding of how cycling has progressed in the Belgian capital, as well as tracking best practices in cities elsewhere to get people moving on two wheels.

More than just bikes

In the broader debate about mobility, bicycles have become a focal point and often come to mind as soon as the discussion starts about driving in Brussels.

To a large extent bicycles have become emblematic of the debate about cars, although having fewer combustion engines motoring through the city isn't just about reclaiming roads for bikes. Limiting cars comes with obvious health benefits and economic advantages, even without an accompanying rise in cyclists.

But the debate is often politicised, leading to high profile "bashing" of bikes, says Florine Cuignet, head of Brussels policy for GRACQ. She describes the disingenuous arguments against expanding cycle infrastructure, that depict mobility as a zero-sum game. "Some MPs say that the Brussels Region has spent enough on bicycle infrastructure and we should instead put money into public transport, which is universal. Though it's true that bikes can't be used in all situations, mobility overall benefits hugely from promoting cycling."

Whilst GRACQ is directly concerned with cycling, the overall aim should be to reduce journeys by combustion vehicles as much as possible. "Active transport goes hand in hand with public transport, we're not competing."

Credit: Belga

In light of the approaching local elections, the need to maintain political pressure to invest in cycling is critical. Mobility in Brussels has become a battleground for some parties who take issue with plans to disincentivise car use.

It's a dispute that has been exacerbated by the media, Cuignet sighs. She cites the example of Bois de la Cambre, which had been closed to cars for numerous reasons: improving the pedestrian space, making it safer for sports, and reducing pollution, to name a few. "But it was presented as a scheme to replace cars with bikes, portraying the two transport modes in opposition."

Not only a reductive portrayal of the issue with cars, the idea that cyclists are enemies of motorists is difficult to dispel, which doesn't help when trying to have constructive discussions about this sensitive issue.

Streets fit for the future

Yet it's hard to get around the fact that increasing space for bicycles and pedestrians will inevitably mean limiting space given to cars. There's no question that the biggest barrier to people cycling in the city is the danger of sharing roads with cars. "To make more space for bikes it is often necessary to reduce space used by cars," Cuignet concedes.

Dedicated bicycle lanes are fundamental to ensuring safety but with only a finite space available, they often come at the cost of car lanes or street parking. Moreover, these must be suitable for the rise in cyclists. Inserting a narrow lane on a street is counter-productive: this strategy fails to improve safety since it compresses road users. "We have to make sure we are creating bike lanes that will accommodate many more riders," Cuignet affirms. "It's about having a vision for the future."

To complicate matters, securing the permits to build bike lanes poses an immense challenge in Brussels. It was only thanks to a great effort by Pascal Smet (former Brussels Mobility Minister) that there is now a complete ring around the Inner Ring. Making this into a continuous network required coordinating with numerous communes.

Making Brussels' bike infrastructure fit for a time when there will be many more cyclists is a key concern. Credit: Belga

To get more people on bikes, poor cycling infrastructure is almost as bad as none at all. Fears about a lack of safe cycle space can keep people driving rather than switching to a bike. Even if this insecurity is just a perception, it becomes a barrier nonetheless. Although there are rarely more than two cyclists killed on Brussels roads any year, Cuignet explains that most people think this is much higher.

More common are the less serious transgressions that deter potential cyclists. "There's a big problem with insults from drivers, people who have parked on cycle lanes, cars passing too close... it often seems to people on bikes that motorists have a level of impunity," Cuignet says.

Progress in numbers

In 2022, the Brussels-Capital Region spent €16 million on cycle infrastructure. Spending on roads and streets was 11 times greater (€184 million). This comes in the context of a decline in driving and a sharp rise in cyclists.

David Leisterh, leader of the MR party in Brussels and formator in the region's French-speaking negotiations, has often pointed to Copenhagen as an example of how cycle infrastructure should be financed. It's a model GRACQ would be glad to see Brussels emulate, highlighting that the Danish capital has spent some €200 million in cycle infrastructure over the last 10 years, on top of national investments. GRACQ estimates that €25-30 million is needed for the Brussels network.

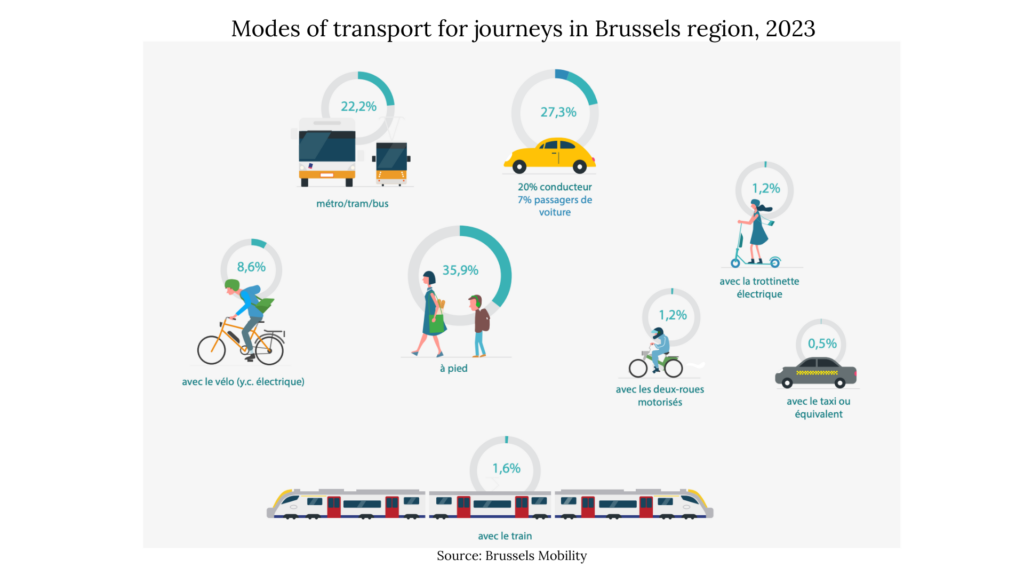

According to data gathered by the public service Brussels Mobility, the large majority (85%) of journeys in the capital remain within Brussels (rather than journeys entering or leaving the region). Of these, two-thirds of journeys are 5km or less, making bicycles an ideal transport to promote. And though in 2022 there were more than four times more cyclists at rush hour than in 2010, cyclists are still far from being the transport of choice, accounting for only 8.6% of Brussels journeys last year, compared to 27.3% for cars.

Despite the issues that arise from portraying mobility as a battle between transport modes, competition for the finite resources of street space and public funds is a reality. Cuignet highlights disparities in regional financing: the €16 million spent on cycle-related policies in 2022 is dwarfed by the €1.12 billion spent on public transport in the same year.

Though the STIB network is undoubtedly a vital resource, Cuignet questions some of the major projects that have come at enormous cost. "Metro 3 is now projected to cost €4.7 billion – that's a colossal budget that could still grow." The work will use all the federal funds allocated by Beliris, which oversees spending on public projects in the capital.

"But some of this was supposed to be for creating bicycle lanes... (GRACQ is) not saying we should stop developing public transport but we have to acknowledge the broader implications of such huge spending commitments. It's a political choice."