Belgium's cordon sanitaire is a pact between the political groups not to work with the far-right. But despite this long-established agreement, Vlaams Belang is now part of the ruling majority in four Flemish municipalities.

Following the local elections last month, the Flemish far-right Vlaams Belang party made it into the governing coalition in three municipalities – Ranst, Brecht (both in Antwerp) and Izegem (West Flanders) – and even has an absolute majority in Ninove (East Flanders).

"This is a further step in the process of normalising Vlaams Belang. For the first time they can really (co-)govern in four municipalities – which is more than expected," Dave Sinardet, professor of political science (VUB), told The Brussels Times.

The party is co-governing in three municipalities. But in Ninove its local 'Forza Ninove' list won 18 of the municipality's 35 seats, bypassing the need to form a coalition with any other party.

Vlaams Belang's Guy D'haeseleer pictured during a meeting of 'Forza Ninove'. Credit: Belga/Nicolas Maeterlinck

While this means the far-right will indeed govern in Ninove, the cordon sanitaire has technically not been broken as none of the other parties agreed to work with them. Still, Forza Ninove's list leader Guy D'haeseleer reached out to the local N-VA branch to cooperate, but his proposal was firmly rejected.

In the other three municipalities, Sinardet confirmed that the cordon was indeed broken – even if he is unsure what Vlaams Belang can accomplish in the coalitions that they entered. "At the local level, they are very eager to co-govern."

"In Izegem, for example, they went as far as signing a document renouncing pretty much their entire ideology and programme as a condition to join. They are entering majorities without it being entirely clear what their contribution to the coalition is, in terms of content," Sinardet said.

However, he also pointed out that in the municipalities where the cordon was broken to work with Vlaams Belang, this did not happen for ideological reasons or due to popular pressure. Instead, it happened as a result of "banal local politics," Sinardet explained.

Local 'hotchpotch'

"It is not as if the local lists were immediately jumping for joy at the prospect of a coalition with Vlaams Belang. The formed majorities are the result of party members not agreeing with other coalition partners, disagreements about the number of city councillors or personal conflicts between party members," he explained.

In Ranst, Vlaams Belang finished third with 14.6% of the votes, behind the local list 'PIT' and N-VA with 34% and 25.2%, respectively. The same is true in Brecht, where the local 'nu2960' list won the elections with 44% of the vote, followed by N-VA (30.5%) and only then Vlaams Belang (21%).

For Izegem, the local 'STIP+' list convincingly won with 32.7% of the vote, followed by N-VA (25.3%) and only then Vlaams Belang (17.4%). "While the party did not do badly in these municipalities, it certainly is not the case that Vlaams Belang scored exceptionally high either."

Local politicians during a press conference of PIT, Vrij Ranst and Vlaams Belang, in Ranst on 20 October 2024. Credit: Belga/Nicolas Maeterlinck

Additionally, the fact that the cordon sanitaire is still respected at the Flemish and federal level, but has now been broken in these three municipalities has to do with the fact that many of the local lists – PIT in Ranst, nu2960 in Brecht and STIP+ in Izegem – are not affiliated with a traditional party.

"The threshold to cooperate with the far-right is much lower at the lower level: many lists are not local branches of the traditional national parties, but a hotchpotch of local figures and characters," Sinardet said.

What is the cordon sanitaire exactly?

The term cordon sanitaire has its origins in agriculture, where it indicates a kind of protective circle that is placed around a farm to keep an infectious disease out.

In Belgian politics, it came into widespread use in 1991, when the traditional parties agreed to exclude the far-right party (then called Vlaams Blok) from government after the party gained an unprecedented number of votes during the federal elections.

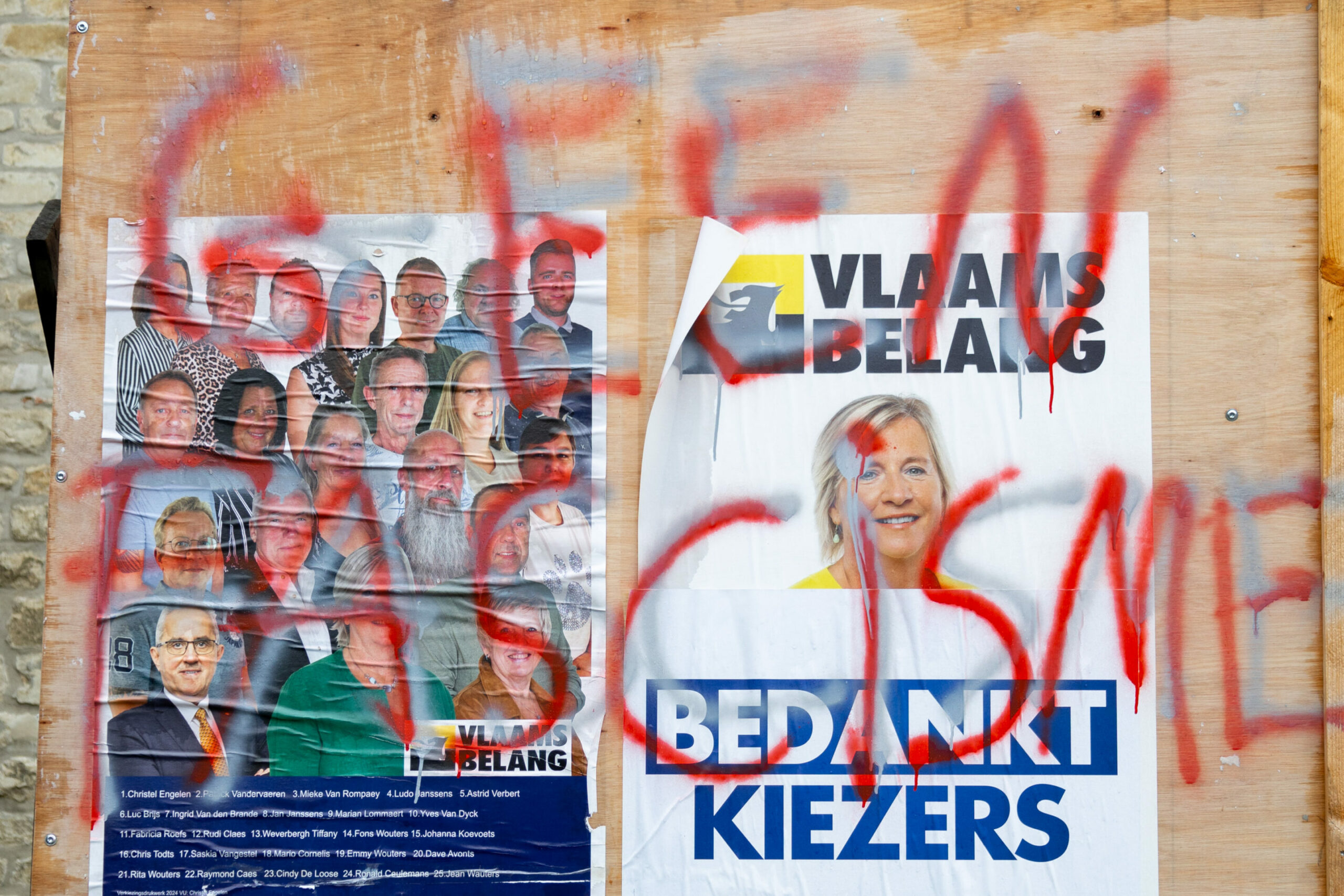

'Geen fascisme' (No fascism) written on election posters in Ranst on Monday 21 October 2024. Credit: Belga

It meant that the far-right was effectively blocked from entering any level of government, as all other political parties agreed not to form a coalition with them, citing the party’s racist rhetoric.

After Vlaams Blok was convicted of breaching the anti-racism law, the far-right party renamed itself Vlaams Belang in 2004. However, the political cordon sanitaire remained in place against the party.

In contrast to when it was first established, there is no longer a written agreement between the parties not to cooperate with Vlaams Belang, but the verbal agreement is still in place.