Supporting victims one step at a time: redemptive potential of the EU Directive on combatting violence against women and what it means to be a custodian of victims’ rights.

As the number of domestic violence cases continued to rise during the pandemic, Aleksandra Ivankovic’s job has never felt more relevant. In her role as Deputy Director of Victim Support Europe she deals with all types of crime, from terrorism to online fraud. Listening to victims and ensuring their voices are heard is a key part of her work, as is looking into different types of gender-based violence, such as rape and other forms of sexual violence, cyber stalking, and domestic abuse.

Changing our criminal and civil justice systems to make things better for victims is a labour-intensive process and even more challenging during these unstable times. Aleksandra tells The Brussels Times how Victim Support Europe has been advancing victims’ rights and support services and how her personal experience helps her champion the rights of others.

On 8 March 2022, the European Commission launched its long-awaited proposal for a Directive on combating violence against women and domestic violence.

Many people feel this new law will be a breakthrough, that this time we can actually change things. How do you feel Aleksandra, should we feel hopeful?

Yes! But also no – at least not without a lot of political will and hard work. The proposal is a first step towards an all-encompassing EU-wide standard that combats violence against women and responds to the specific needs of its victims. It responds to the EU’s strong commitment to do more for victims of gender-based violence. Yet, it is just the first step; a proposal from the Commission. It still has to be approved by the Member States and the European Parliament, and we know there will be push back.

In 2017, the EU signed the Istanbul Convention. However, due to objections by some Member States, this key instrument guaranteeing the rights of victims of gender-based violence has still not been ratified by the EU. The new EU proposal is intended to break this deadlock: finally, all member countries will have to classify nonconsensual sex as rape under criminal law. Female genital mutilation, cyberstalking and harassment, and what some would call 'revenge porn', but which we refer to as the nonconsensual sharing of intimate images, will also become criminal offences. Just as importantly, the proposal addresses the wide-ranging needs of victims – in particular the need for support.

How prevalent is violence against women in the EU?

In brief – unfortunately, we don’t know precisely, but we know it exists everywhere and is prevalent. Data collection methodologies vary between EU Member States, we don’t have any way of knowing the rate of unreported crime as it’s, you know, not reported. The only comprehensive study, conducted by the EU Fundamental Rights Agency, dates back to 2014. It found that one in three women had been a victim of physical or sexual abuse since the age of 15, while 43% of women had experienced some form of psychological violence, and 18% had been victims of cyberstalking. This is similar to results found by a global UN study on women. Let’s put it this way – I personally don’t know a woman who has never been a victim of some form of gender-based violence.

Gender-based violence, domestic violence, is certainly the major cause of physical and psychological injury to women. Statistically speaking, the most dangerous place for a woman is not the street, it's her own home. Women share their homes with their abuser, a trauma that we are only now recognising. There's an amazing book, “Trauma and Recovery”, by Harvard psychiatrist Judith Herman in which she compares the trauma experienced by war veterans to that experienced by survivors of domestic violence, it’s well worth reading to get an insight of the harm caused by abuse.

Education is a long-term solution. How do we deal with the problem in the short-term?

We need to support the victims and enforce the laws. A vast majority of crime in general and of gender-based violence in particular is never reported. When it is reported, victims are not believed; if they are believed, cases are still rarely prosecuted because of procedural concerns, lack of evidence, shortcomings of legal definition. When a case is prosecuted, the conviction rates are low; when there is a conviction, sanctions are often inadequate and on the occasions that a victim is awarded compensation, they have to re-engage with the perpetrator to receive the payment.

We see cases where, if there is a lack of evidence against the perpetrator, victims of rape are prosecuted for ‘false reporting’. We see cases in which DNA evidence or even video evidence is not enough, because “she must have asked for it” and because the rapists are married, honourable men. Basically, women are damned if they do, and damned if they don’t report. This is not about weakening the rights of the defence, it’s about making sure the system is balanced, that myths and biases are minimised or ideally removed and that no matter what the outcome, a victim shouldn’t come out of the process even more traumatised and swearing never to go through it again.

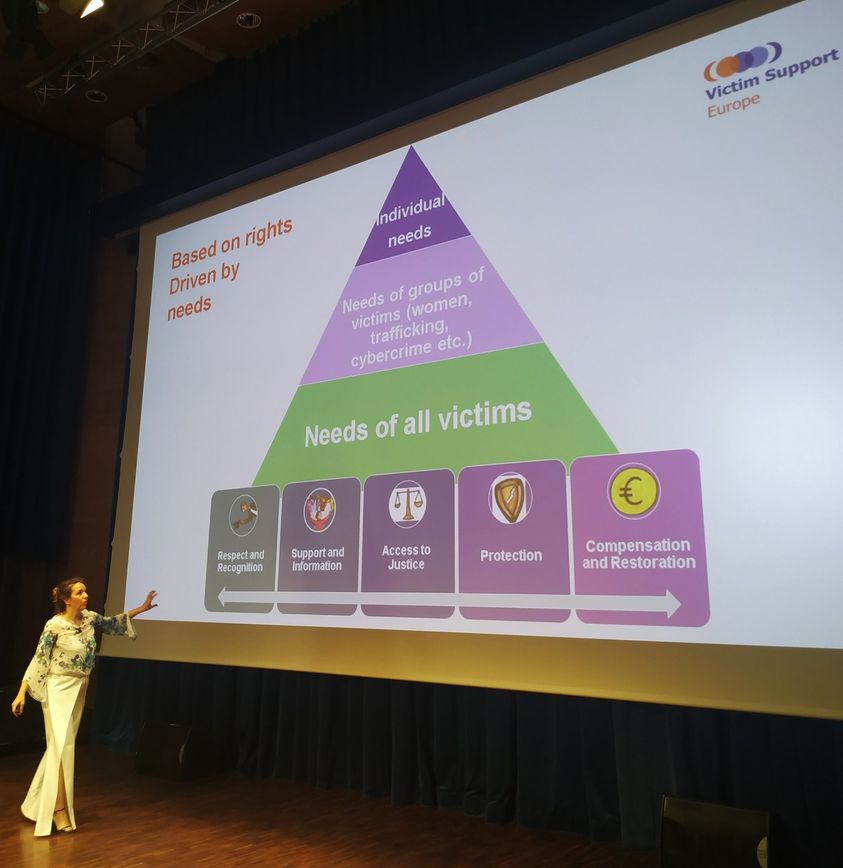

The first time we fail victims is when the crime happens; our primary duty therefore is to prevent the crime from taking place. But once we fail in that, we need to empower and support victims and make sure that they feel heard and believed. This does not mean that each crime needs to end in placing the offender behind bars, but each victim must receive the respect and recognition she deserves, and the support she needs.

No matter the outcome of a criminal proceedings, we can certainly make an effort to reach out to the victims and offer them psychological and other support to help them recover and rebuild their lives. A fundamental shift to achieve this, is the way we measure success in our justice systems. Now, the focus is only on finding people guilty or innocent, and being efficient. We have to include the objective of safe justice – where minimising or preventing harm to victims in the criminal proceedings is as equally important as fair trial rights, and where we measure how successful we are at doing that.

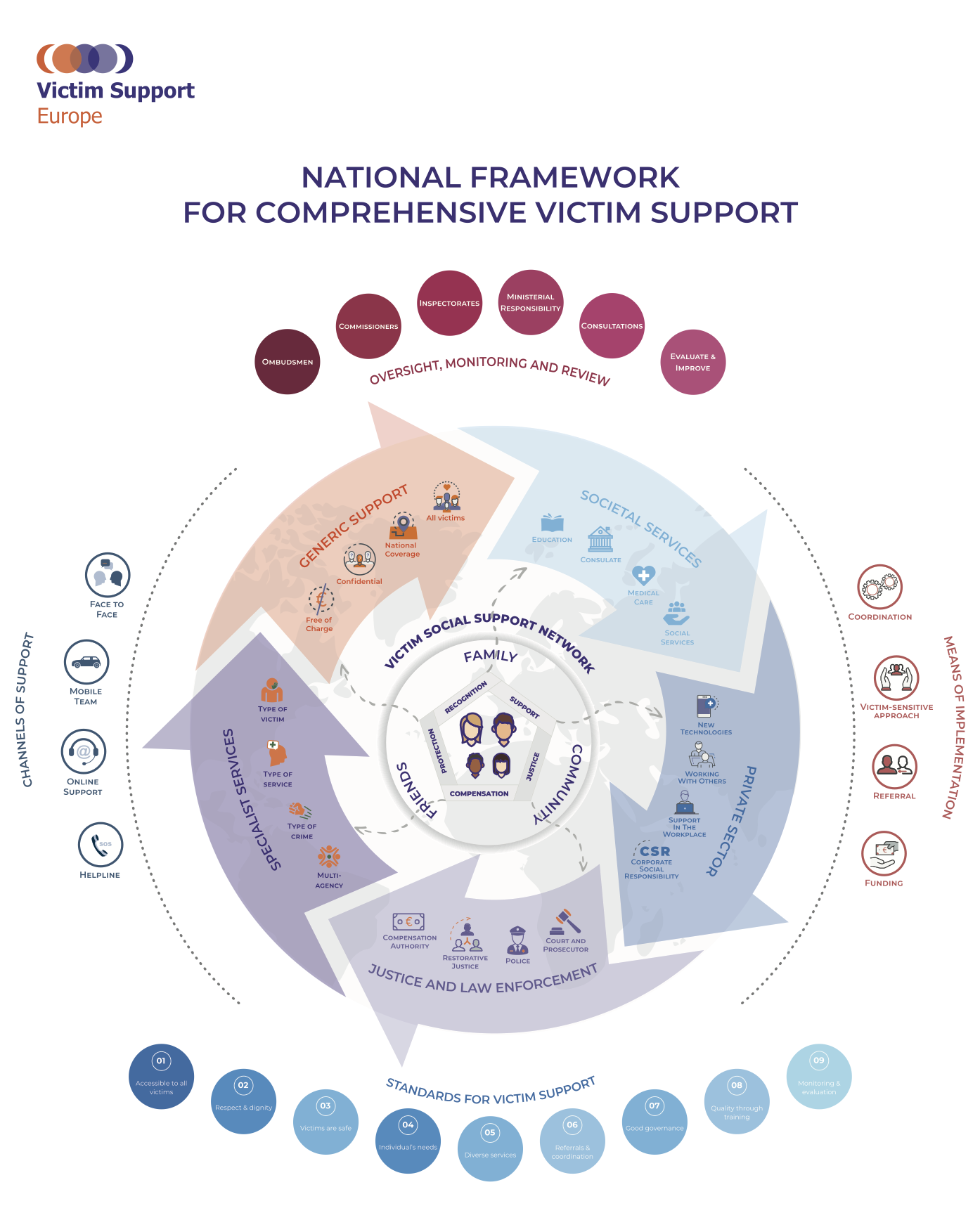

We should avoid failing victims over and over again. Once is already too much! A victim support framework is now being drawn up to help countries direct support towards victims, it will provide local and national governments with ideas on how to create guidelines to suit their own situation. However, today, many generic victim support organisations can help victims of gender-based violence, they have as much experience as specialist agencies, and they are only a phone-call, text message or email away from victims.

2022 is the 10th anniversary of the EU Victims’ Rights Directive. What progress do you think has been made over the past decade?

There has been a lot of progress, but there is much more still to be done.

Through the Directive, victims have been given a voice and a place in criminal proceedings. All EU Member States are obliged to establish national victim support systems and introduce a number of procedural guarantees for victims.

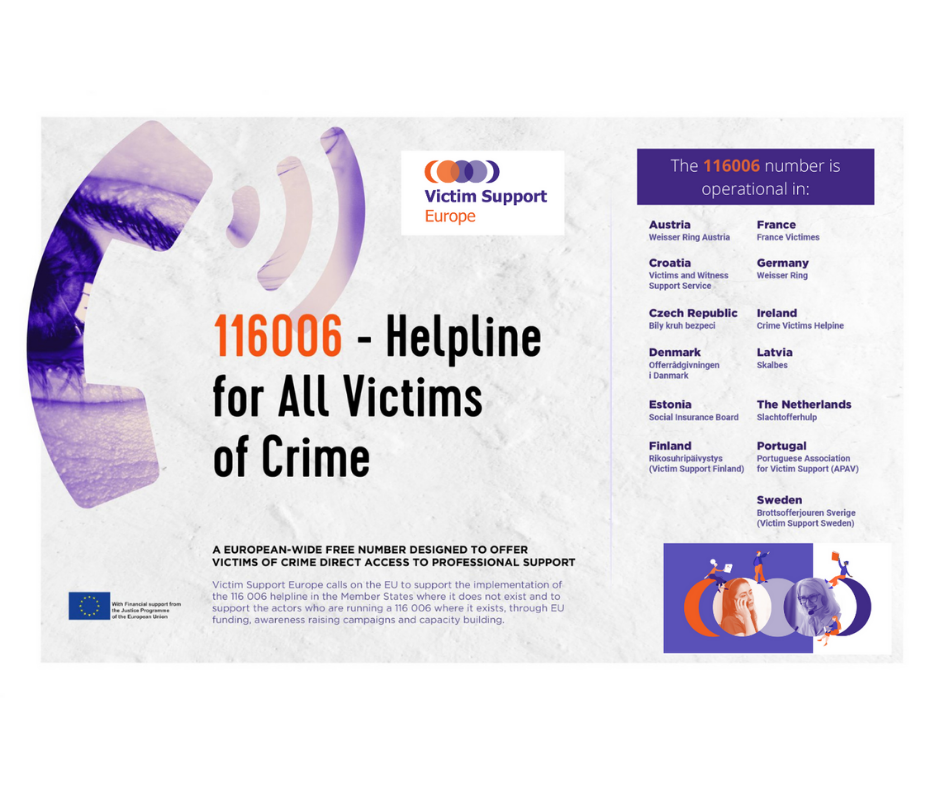

New victim support systems have been developed, 116006 helplines have been introduced in many Member States, compensation systems have been improved. However, a number of Member States have still failed to put in place generic victim support systems. 116006 helplines are only available in 13 of the 27 EU countries. In 2018, we carried out research on the practical implementation of the Directive across the EU and found that not one single victims’ right was applied and respected across all Member States and that not a single EU Member State had fully implemented all victims’ rights.

So, there are successes and still some challenges. The only thing I can say is that the struggle for victims’ rights will probably never end, because we will always have crime. We will keep doing what we can about it, but this is not a task for just one international NGO or for just our members. Our schools, and our governments, doctors and everyone else in society should also be involved.

Recently some countries have argued they can’t implement the Victims’ Rights Directive because of current economic issues.

According to the EU’s Commissioner for Equality, gender-based violence against women costs the EU approximately €226bn per year. Evidence shows that if you get this right, it is on the whole much cheaper to effectively implement victims’ rights than to do nothing.

The way we see it – victim support is not a cost, it’s an investment. Preliminary evidence indicates that for every one euro you spend on support, at least five euros are saved elsewhere.

Of course, you will have to increase grants for support services including victims’ shelters or spend more on psychological or legal support. The police training budget might be a bit higher but this actually results in better more effective actions, and there will be lower health care costs, industry will benefit from fewer absences and the justice system will reduce its costs for dismissed cases. Victims who have better support will be more reliable during a trial, so our justice systems will become more effective. Costs and benefits must be looked at in the round and in the longer term. There really is no excuse for not fully implementing the Directive, at least as the minimum standard expected.

Not only do you reduce costs in the medium to long term, there are multiple ways that States can find funding to implement rights and services, to minimise the impact on Treasury budgets. VSE carried out a report for the World Bank demonstrating that practices such as small additions to compulsory insurance can be deposited into a national victims fund. Some countries donate national lottery money, fine offenders and earmark the money for victims’ services, or if offenders receive salaries, divert a proportion towards victims’ issues.

Overall, there is no excuse, supporting victims of gender-based violence is a choice, unfortunately, politicians are choosing other issues above violence against women.

We have seen that several factors play a role in the poor implementation of the Victims’ Rights Directive, such as a lack of data on the implementation of rights and the absence of legal remedies for victims when their rights are violated.

To avoid existing EU legislative pitfalls, what rights and obligations should the Commission include in the new gender-based violence Directive?

The only way for us to understand the scope of the problem is to have reliable data. So, access to data is key, otherwise, we will find ourselves at an impasse – we fear that governments behave in a ‘no data, no problem’ fashion, while we are accused of exaggerating the problem. The answer may lie somewhere in the middle, but without data, we simply don’t know.

Another fundamental point is that victims’ rights are not as enforceable as are the rights of offenders. If you breach an offender’s right to remain silent or to legal representation, the case may be thrown out; if there is a failed prosecution or an overturned conviction, offenders can easily claim compensation. In most violations of victims’ rights, there are no sanctions, no consequences. This must change! Victims’ rights must be enforceable and have consequences, otherwise, what is the point?

We understand this is an extensive agenda. These are not small recommendations, yet they are largely incremental – aimed at making victims’ rights a reality. These are changes which best reflect the most successful approaches to implementing rights – ambitious, yet realistic. We hope they will prove useful as the Commission considers its next steps for victims of gender-based violence in the EU.