Historians should be ready to work with members of the public who have hoarded human remains from the battlefield of Waterloo for decades – even if, in doing so, they may have acted illegally.

“It would be better if people informed the police and authorities when making such discoveries in the first place, but the fact that they are now doing the right thing and handing finds in for DNA analysis is positive,” says leading historian and Waterloo specialist Dr Bernard Wilkin, who is based at the Belgian State Archives in Liège.

“It’s possible that other relics from the battle still exist in private homes in the country. I hope the ‘owners’ will be encouraged to bring them to the attention of our experts who can examine them properly."

End of empire

Despite Dr Wilkin’s ‘bring-out-your dead’ plea, it is very rare for human remains to be found on the battlefield. Only two skeletons have been unearthed in the past decade.

More than 10,000 men lost their lives and 20,000 horses were killed or severely maimed during the epic battle on 18 June 1815, in which the Duke of Wellington and Field Marshal Gebhard von Blücher joined forces to definitively end Napoleon’s hopes of resurrecting his empire. The bodies of the dead, man and beast alike, were piled high in burial pits or burnt on pyres.

Yet no mass graves have been found. Research by Dr Wilkin and fellow experts Professor Tony Pollard of Glasgow University’s Centre for Battlefield Archaeology and German military historian Robin Schäfer suggests that farmers later dug up the bones which were ground down and sold as fertiliser or for use in refining sugar beet.

Attic find

Dr Wilkin played a key role in the recent restitution of two separate sets of bones which were removed from the battlefield, in one case nearly half a century ago.

The 40-year-old academic first heard about the existence of the latter remains after giving a lecture at the Waterloo Memorial last November. An elderly man approached him after his presentation and said: “I’ve got Prussians in my attic.”

Credit: History Hit

Wilkin was shown photographs to prove it and the man, who does not wish to be identified, later handed him two skulls, a box of large bones and fragments of clothing and shoes for analysis.

One skull shows evidence of a severe wound, mostly likely caused by a bayonet thrust in the victim’s face. Tests have already shown that the bones belong to four individuals, one of whom was in his 30s, a pipe smoker and right-handed.

‘Passionate interest’

The bones were originally unearthed during construction works in the late 1970s near the Lasne river in Plancenoit, where Prussian and French troops were engaged in heavy fighting on Napoleon’s right flank. It seems likely from the fragments of clothing and shoes that the bodies are indeed those of Prussians.

Jean-Pierre Beirnaert of the Guides 1815, which run battlefield tours, believes that the bones were initially taken by a respected local figure known for his “passionate interest” in the battle. It is understood that he kept them for several years before handing them to the current ‘owner’ who planned to display the remains in a museum but changed his mind after deciding it was “unethical” and moved them to his attic.

The skulls and bones are undergoing forensic and anthropological analysis by Professor Philippe Boxho from the University of Liège and Mathilde Daumas of the Université libre de Bruxelles at the city morgue in Liège. Strontium isotope analysis could help confirm the nationality of the victims.

Grenadier Guards

Dr Wilkin was subsequently introduced to a metal detectorist, also wishing to remain anonymous, who had another cache of bones, which come from six or seven men. The remains were uncovered next to a cannonball, picked up by the detector, close to the Lion Mound. The bones are likely to be those of English troops, defending the centre of Wellington’s line: they were found with a badge bearing the insignia of the First Regiment of Foot, later known as the Grenadier Guards for their role in repulsing Napoleon’s crack Imperial Guard in the closing stages of the battle.

These bones, which are in much more fragile condition than the Plancenoit remains, are being examined by Dr Caroline Laforest, an osteoarchaeologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels. Laforest is also carrying out tests on a skeleton found last summer at Mont-Saint-Jean farm by a team from Waterloo Uncovered, a charity helping veterans and serving military recover from combat trauma. The farm served as the main allied field hospital during the battle.

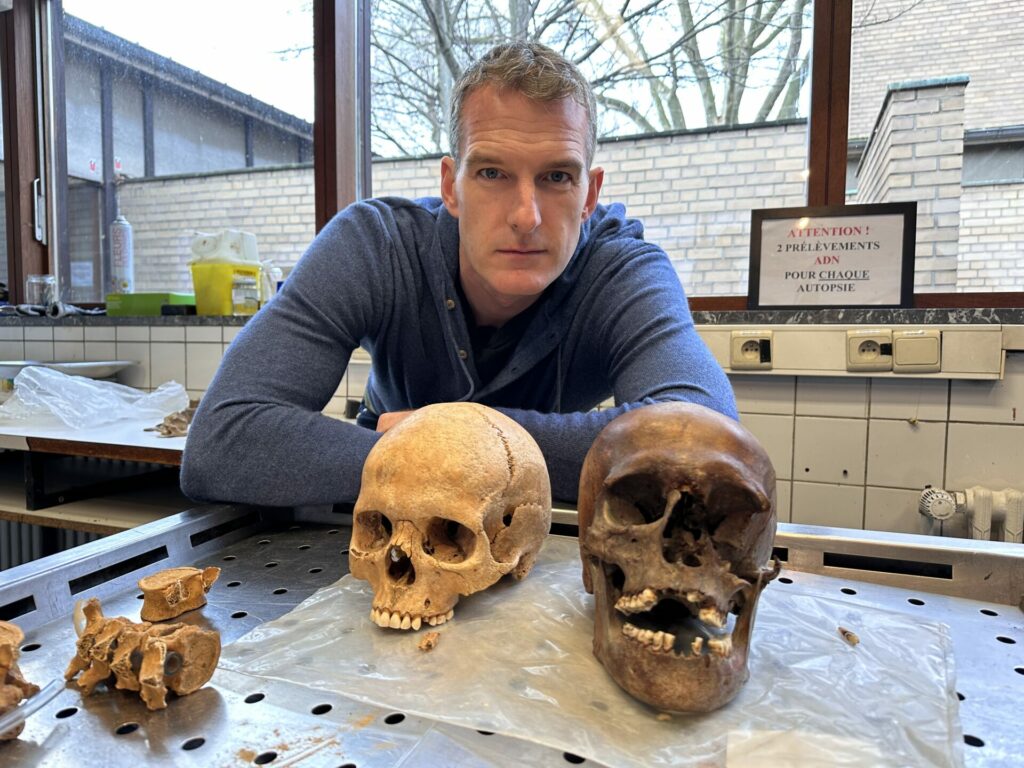

Dan Snow and Dr Bernard Wilkin at the morgue in Liège. Credit: History Hit

Both sets of bones were recovered from homes in Walloon Brabant.

“We hope that the tests will allow us to reconstruct the faces of the ordinary troops. Perhaps for the first time, we will see how private soldiers and lower ranks looked instead of the generals,” said Dr Wilkin.

The Belgian is working with Dan Snow, a renowned British television historian, to tell the story of the bones and their importance in better understanding the sheer brutality of battle in the Napoleonic era.

‘Corps-à-corps’

This week Snow was filming in Liège (with Wilkin), Waterloo and Brussels for his History Hit online channel.

Speaking to The Brussels Times, Snow said that the remains bore witness to the savage violence of the battle, in which hand-to-hand fighting was commonplace. “The French call it ‘corps-à-corps’ which is an even better description,” he said.

While hailing the latest developments as “very important and exciting news” for historians, Snow admits he also feels “conflicted” about filming human remains. He said cancer doctors face similar dilemmas. They can get “excited” about a medical breakthrough but at the same time are daily confronted with the reality of patient deaths, he added.

Related News

- Waterloo bones find their way back to the battlefield

- Archaeologists unearth skeleton dating from Battle of Waterloo

The History Hit footage will be released for subscribers today (3 February) and during the next few days via YouTube. A podcast on the topic will be released on 9 February.

Once the DNA tests are complete, Dr Wilkin and Dan Snow hope that the bones will receive a proper burial. The German War Graves Commission has already said it wishes to take care of the Prussian remains, according to Robin Schäfer.

Dr Wilkin says anyone in Belgium who wishes to hand in remains or other relics for analysis, even if they were obtained without authorisation, can contact him at the State Archives.

*The author is a member of the Guides 1815 and volunteer with Waterloo Uncovered.