Lurking below our feet is a 350-kilometre long labyrinth of pungent, dark and damp tunnels: the Brussels sewer system. With its claustrophobic and dingy passages, many find this largely unknown underground world revulsive, but few are aware of how vital it is to the functioning of the city.

"The sewers are a mirror image of what's happening above ground," says Aude Hendrick, the curator of the Sewer Museum, near the Porte d'Anderlecht. She describes the smaller sewers connecting houses like streets, while the larger treatment plants and storm basins act as underground avenues, boulevards and cathedrals. Dating back several centuries, Brussels' efficient and comprehensive sewer system is a true feat of engineering that developed at the same pace as the city.

The city's sewers were initially designed to collect rainwater from roofs and channel it into streams and rivers. Brussels' first real sewer system, however, dates from the end of the 18th century, when locals gradually opted for full sewerage, with wastewater adding to the rainwater. Before this, people would dispose of their waste into the Senne river and all excrement was sold to farmers in the countryside to enrich the fields. That was until the Senne became so polluted that city authorities covered it up.

Up shit creek?

From the mid-19th century, the city developed mains drainage. Houses could be connected to the public sewer system, and the water was sent outside Brussels before returning to the river. But it still meant that for at least 150 years, wastewater was channelled back into the rivers and the North Sea. “It was an ecological scandal,” Hendrick says.

It was only in the year 2000 that Brussels began to treat its wastewater at treatment plants, and the entire city was finally connected to the sewers in 2007. Hendrick says the Brussels South wastewater treatment plant is now the second most efficient in Europe.

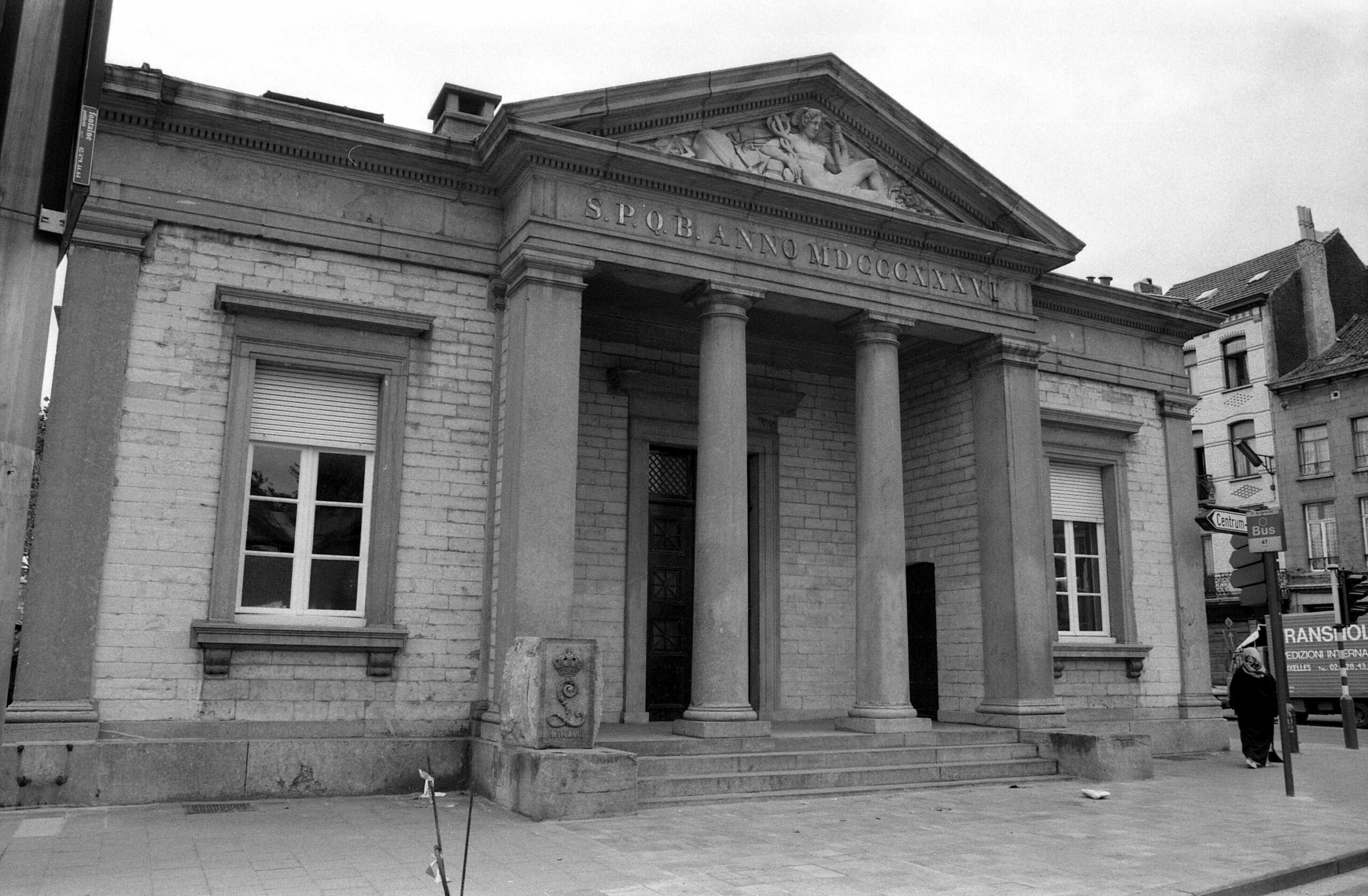

The inauguration of Brussels Sewers Museum on 30 May 1988. Credit: Belga photo archives

Monthly analyses from Brussels Environment confirm an improvement in water quality in recent years. However, climate change is triggering increasingly heavy rainfall, causing the sewers to overflow and making water treatment trickier. As temperatures rise, so too will the threat to water quality.

In addition to extreme weather conditions, people regularly discard harmful chemicals and other toxic products down the sink and the toilet. These range from bleach and paint to cigarette butts, chip fat and baby wipes, which cause blockages (in Britain, they are affectionately known as fatbergs). As they pass through untreated, they end up in Belgium’s rivers and canals, and the cycle continues.

Effluence influence

"We should only send to the sewer what we want to go back into the natural environment. After all, sewers are not bins," Hendrick says. "A cigarette butt alone pollutes 500 litres of water because it contains so many chemicals. But people still throw them down the drain because that's what they’ve always done. Water must be kept as clean as possible so that it can continue to be used."

Sewers not only ensure water quality but also prevent the spread of infectious diseases. Since 2020, Belgium has been analysing sewage samples to map the circulation of viruses in the population. In January 2023, they also started testing the wastewater from flights coming from China to gather more information on the possible spread of new Covid-19 variants.

So, if sewers are so important to public hygiene and disease prevention and act as a "mirror image" of life above ground, why do we turn up our noses at the thought of them?

"It's everything we reject," Hendrick says. "When you flush, you don't want to think about what happens afterwards."

The Sewer Museum aims to make people reflect on exactly that. It is one of the only museums in the world that allows visitors to explore the city’s sewer system and learn the hidden history of how the city disposes of its waste.

The City of Brussels had long been proud of its sewers and felt that it deserved to be showcased to the general public. The museum was opened in 1988, was completely refurbished in 2007, then taken over by the Department of Culture and reopened in 2015 with an outreach programme and a range of temporary exhibitions.

Though it started as a tourist attraction, its primary objective now is raising ecological awareness and “helping people understand that, throughout our everyday actions, we can ensure water quality."

But how can Hendrick and her team overturn the centuries-long negative image? "We aim to draw the public's interest to the unusual nature of what's going on beneath our feet," she says. "It's a bit of a strange world, but an intriguing universe. I'm learning all the time, there's so much to discover."

Sewer Museum curator Aude Hendrick.

A historian by training, Hendrick has been the museum's curator for seven years and enjoys researching scientific subjects and transforming them into something more accessible. "I think people are more ignorant of the sewers than disinterested. Because we're not interested in things we don't know, so we need to make them better known," she says.

Image upgrade

The museum is now working to make this unknown underworld known through campaigns, school programmes, exhibitions and even recruiting influencers.

The awareness-raising campaigns – such as Ici commence la mer ('This is where the sea begins') – have been running since 2019, particularly around World Water Day on March 22. Associations such as Canal It Up also promote cleaning up the canals and spreading awareness of the pollution in canals from overflowing sewers.

"All these awareness-raising actions by public authorities, the museum and associations are gradually making people a little more concerned. But it's still a work in progress," Hendrick says.

The museum aims to educate people on the importance of sewers from a young age, by engaging schoolchildren as they learn about the water cycle and providing information packets for teachers. In 2023, there was also a partnership with the Smurfs, including workshops and fun activities for children.

Inside the sewers.

The museum has also started thematic temporary exhibitions, the first of which is called ‘Rattus’ which was inspired by the high number of visitors who asked whether they would see the reviled rodents during their visit to the sewers.

"Despite being the emblematic animal of the sewers, we know very little about rats. We know more about the habits and customs of blue whales or polar bears, whereas rats have lived in our neighbourhood for centuries," Hendricks says.

The exhibition gives visitors a new, more positive perspective on rats. They eat much of the food waste that ends up in the sewers, thereby preventing blockages in the drains. Although many view them as vectors of disease, they are part of the ecosystem.

"Rats are a bit like the sewers," Hendrick says. "They scare you because you think they're dirty. But once you become interested, you can also see how useful this network is and that if it's not properly maintained, it can really cause disasters."

The museum also hosted an exhibition in partnership with Surfrider on microplastics, as well as an exhibition to mark the 150th anniversary of the vaulting of the Senne. The next theme, starting in September, is rain and how it is managed in the city. "It's a fairly basic theme, but one that is interesting," Hendricks says.

As well as temporary exhibitions, the museum also shines a spotlight on the invisible work of the égoutiers (sewer workers). As you wander through the endless winding tunnels, you get a sense of the life of the hardy workmen who spend their days in this dangerous, dark, humid environment. The museum explains how safety standards have evolved over the years for this under-appreciated profession.

Although the health risks seem obvious today, it was only in the 1900s that the sewer workers realised that if gardeners wore gloves, so should they. The uniform that was originally composed of just a beret and leather boots now includes waterproof overalls and boots, gloves and helmets, as well as goggles and gas detectors. Additionally, sewer workers can now only work underground for a certain number of hours a day.

Bill Gates effect

Hendrick says that the museum wants to change its image by raising its profile on social networks and has been engaging with influencers to do so. Bill Gates toured the museum and sewers last November to mark World Toilet Day, which naturally got people talking – and visiting.

"We recorded 34,081 visitors in 2023. November and December were significantly busier compared to 2022, up 29% and 98% respectively, and Bill Gates's visit is probably one of the reasons for this increase," she says about the house call by the billionaire healthcare campaigner. "It's a stroke of luck for the museum to have welcomed such a high-profile figure. It really puts the museum on the map internationally."

Bill Gates visiting the museum

The museum also receives requests from artists to film music videos, such as Belgian artists Arnaud and Zwangere Guy. The Royal Family also paid a private visit.

These initiatives are gradually transforming the unpleasant image of the sewers into something more positive, encouraging visitors to reflect on how waste is managed and to question the environmental impact of our attitudes and actions.

"We want people to leave the museum with almost more questions than they had at the start," Hendrick says. "Or at least to have asked themselves questions they would never have thought of before coming here."