For the first time in Belgium, people in Flanders will no longer be legally required to vote in the local elections on Sunday 13 October. The municipal elections will be slightly different than usual, but how could it change things?

As of this year, Flanders has abolished to obligation to vote which raised the question about what this will mean for the region's voter turnout and party results.

Some hope the decision will "liberate" the region from people voting for the far-right Vlaams Belang party as a form of protest against the system (because they are legally required to), but political experts disagree.

"It is often said that Vlaams Belang voters are dissatisfied voters. Therefore, people assume that if compulsory voting were abolished, those voters would drop out," Stefaan Walgrave, political scientist (UAntwerpen), told The Brussels Times. "But that may not be the case. Those who are angry with the political system also engage with it."

Convincing voters

Indeed, those who are more likely not to vote due to the abolition of the legal requirement will be people with lower education qualifications and lower incomes. While these two criteria can also apply to Vlaams Belang voters, one thing in the party's favour is that their voters are quite motivated and radical, Walgrave said.

"People who position themselves on the extreme sides of the political spectrum are more likely to vote," he said. "In Vlaams Belang's case, this largely makes up for the first two factors. Their strong political ideas will lead them to the polling station."

The party has always been in favour of the abolition of compulsory voting, Vlaams Belang spokesperson Alexander Van Hoecke told The Brussels Times. "We think it is good that politicians have to go out and convince voters of the importance of their vote – something that Vlaams Belang has been doing for years."

"We are confident that our voters are convinced of their vote and we do not fear a negative impact of the abolition on the results for our party," he added.

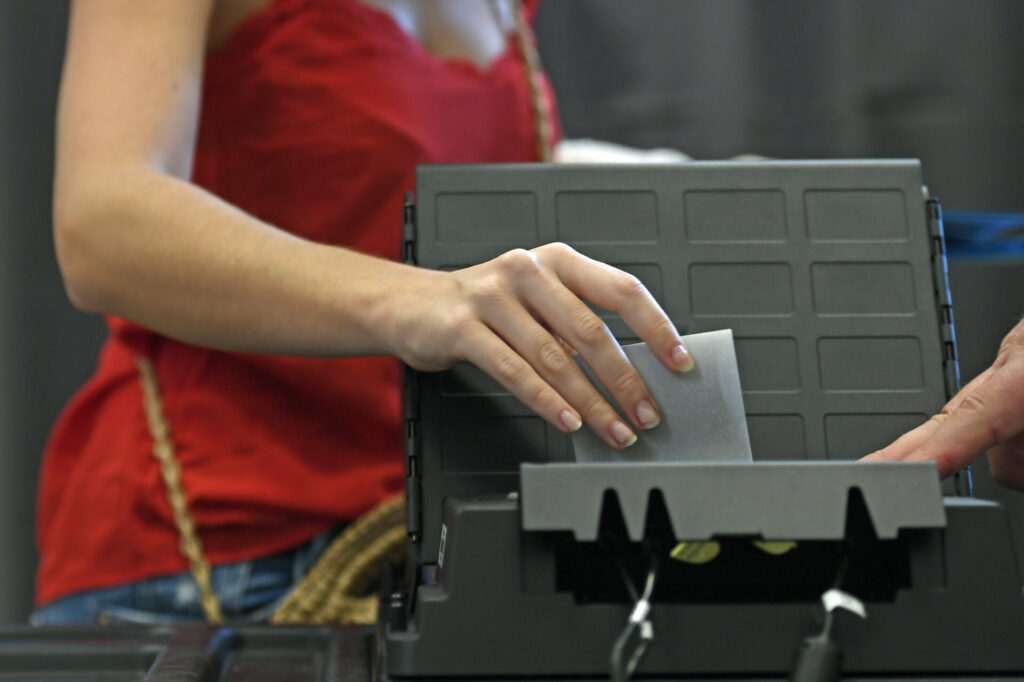

People queue in line at a polling station. Credit: Belga/Hatim Kaghat

Among those with a lower socio-economic status and no strong political convictions, turnout is expected to drop significantly, which is the main reason why political scientists are not in favour of abolishing the requirement.

"It would be a shame if those people would stay at home, because it means that only the 'strongest' in society will continue to vote," Walgrave said, citing the egalitarian effect of compulsory voting as the most important argument for keeping it.

"It ensures that more people vote and that politicians have an eye for the interests and preferences of the entire population, not just the most privileged layer," Walgrave said. "If the 'weak' do not vote, political parties are less obliged to take them into account and they will not be punished for that electorally, because those 'weak' people will not vote anyway."

This also means the signal of dissatisfaction, of people saying "this cannot continue like this", is lost to some extent, he explained. "While those casting a protest vote may vote for extreme parties, at least they do vote and they are therefore heard."

Reflecting the population

Vlaams Belang and its voters often claim they are not heard, in part due to Belgium's cordon sanitaire (which excludes the far-right from all government levels), Walgrave argues that this is not true.

"But Vlaams Belang questions and challenges the other parties in Parliament, in the name of the people who voted for them. So they are still represented," the expert said.

The only way to not be represented is to not use the democratic right to vote at all, he underlined. If the percentage of non-voters is 30%-40%, that also means that the people who sit in parliament are not an accurate reflection of the population.

"If 40% of the people do not vote, politicians are only elected by slightly more than half of the Belgian people. Additionally, the system to distribute the seats also favours bigger parties over smaller parties," he said.

The parties possibly expected to lose votes are radical left PVDA-PTB (-13%) and socialist Vooruit (-13%), according to Walgrave's 'De Stemming' analysis, an opinion poll conducted by De Standaard and VRT carried out at the start of the year. The Brussels Times contacted both parties for a reaction, but did not receive a response by the time of publication.

Credit: Belga / Dirk Waem

While Walgrave does not doubt that the voter turnout in Flanders will be lower than in previous years, he does not think the decrease will be "spectacular."

In part, this has to do with the fact that the abolition is only in place at the municipal level – the elections that people are most likely to continue voting in, according to him. "The closer the system is to the citizens, the smaller the chance that they will drop out."

At the local level, there is more proximity and connection: people know the mayor and likely some of the candidates as well. "The municipal elections are also much less ideological: building a new sports hall is less ideological than deciding on whether to increase taxes for the richest, for example."

Still, the turnout rate will definitely take a hit, Walgrave said. Belgium – which now has a national voter turnout of 90% – will likely evolve to an average 70%-80% voter turnout, but probably not all at once.

"In other countries where compulsory voting has been abolished, there is a downward jump at the start, and the percentage slowly erodes further in the following years," he said. "That also has to do with generations: older people are more likely to continue voting than young ones who have never started, so it simply takes a while for the number of people who vote in the population as a whole to decrease."