Mathieu Michel is struggling to find the right word. We are standing in the imposing cathedral-like atrium of the Palace of Justice in Brussels, known as the Salle des Pas Perdus – which loosely translates as the Hall of Lost Steps. A Belgian State Secretary, Michel has many responsibilities, including digitisation, administrative simplification, privacy and, crucially, buildings administration. He has gamely vowed to be interviewed in English but is already stuck. “How do you say ‘echafaudage’ in English?” he asks. “It’s scaffolding,” your correspondent responds. He raises his eyebrows at the word, which sounds odd to French speakers. But he remembers it, and over the next hour, correctly uses it about 100 times.

Michel is explaining his plans to restore the Palace of Justice, the site of the country’s main law courts, which has, to say the least, a reputation. It was the biggest edifice in Europe when it was completed in 1883 and is still the largest courthouse in the world.

On a scale of a Mesopotamian ziggurat, it has to be seen to be believed. The gargantuan complex looms from a hill over the old city and is thought to have inspired Adolf Hitler’s madcap Germania plans for a new Berlin. The Salle des Pas Perdus alone could fit the Brussels Hôtel de Ville under its 80-metre ceiling. The sheer grandiosity is monumental and majestic, with a touch of the absurd, like a steampunk Tower of Babel.

The Salle des Pas Perdus

Even inside, the building is breathtaking, combining a jumble of elements, from classical Greco-Roman to Gothic via Baroque, in a style labelled as eclectic architecture.

But the 140-year-old law courts are a crumbling wreck. It is currently shrouded in scaffolding, with a €200 million restoration set to be completed in 2028 – at least for the outside. An innocent visitor might wonder why it might take five years for the clean-up job, but this timeline does not tell half the story.

The scaffolding originally went up in 1984 after engineers first noticed cracks in the masonry. Most Belgians have only ever known the courthouse incarnated in a metal cage. At times, the delay has been blamed on red tape, administrative incoherence and sheer inertia, but whatever the root cause, the building remains under wraps.

Indeed, the rusty scaffolding is now so old that it now needs scaffolding of its own. None of the connecting clamps holding the poles together are in use anymore, so when – or, for cynics, if – the scaffolding ever comes down, period tools will be needed to dismantle it. All this adds up to a building that many locals see as emblematic of a wider Belgian dysfunction.

Mathieu Michel

Michel is not here to make excuses for the clutter cladding the courthouse. “It's shameful,” he says. “They put up the scaffolding in the early 80s when they saw the stones had cracks. It was urgent and stopped the stone from falling. But then…nothing. Really, nothing. If someone goes to London, for example, and sees the Tower Bridge with scaffolding for 40 years, what image does it show the world?”

Leaks, cracks, holes and mould

When he joined the government in October 2020, Michel made it a priority to finally complete the repairs and remove the scaffolding. “I told myself, ‘You can do something.’ And maybe we can tell a story about how, one day, nobody will be ashamed of this. I want to give it back. I want us to be proud of this place.”

Leading me around the building, he points out broken windows, leaks, cracks, mould and holes in the ceiling. There are still real repairs to be made to the façade before the scaffolding is removed.

Cicero statue

But Michel has a plan in place for the exterior. A crucial study of the brickwork has already been done, and procurements for the repair work will be launched in mid-February. Work will likely begin in July: some 30 percent of the stones might have to be repaired or replaced (most were sourced from a quarry in Burgundy, which Michel notes is still active and ready to provide new blocks).

Once the repairs are done, the first scaffolding on the main façade, facing Place Poelaert, will come down in April 2024. The facades along Rue des Minimes, Rue aux Laines and Rue de Wynants will follow in two later phases. “The exterior of the palace will all be done in 2028. Everything,” he promises.

The budget for the exterior is expected to be about €80 million. But then there are the concurrent plans for the interior, which Michel estimates at €100-150 million. These are more complex. For example, last October, ceilings in the second basement floor collapsed, and water flooded in, preventing police officers from transferring detainees through to the courtrooms.

The great staircase under the portico

Michel explains that the issues inside go far beyond repairing broken windows or slapping on a new coat of paint. “These are occasional issues. But the main problems are larger and deeper,” he says. “If the ceiling falls, there is a reason. It could be a problem with the water system, but in this building, the water pipes are not accessible. So you have to open all the walls.”

While the original plans have been unearthed, there is no comprehensive overview of all the elements, including the routes of the water pipes and parts added after the construction. “We are mapping the technical geography of the building. We are writing a technical Bible,” Michel says

The lighthouse at the end of the Mall

Michel, 43, is from a storied political family. His brother, Charles, is the current President of the European Council and a former Prime Minister, while his father, Louis, is a former European Commissioner and Belgian Foreign Minister. That, perhaps, gives him a deeper sense of heritage when it comes to the courthouse.

He speaks emphatically about how the Palace of Justice can one day take its place as an emblem of Brussels, like the Atomium, the Hôtel de Ville and Manneken Pis. He talks about the ‘democracy route’ that runs along the Rue de la Régence, or Regentschapsstraat, from the federal Parliament, past the Royal Palace until, at the end, the Palace of Justice. He likens it to the Mall in Washington DC.

“I want the Palace of Justice to be a symbol of a Belgium that respects itself,” he says. “In 2030, Belgium will celebrate 200 years since its declaration of independence. I want the building to play a major role in the bicentenary. It’s a lighthouse. It’s the symbol of justice. It’s a symbol of democracy. When I see the palace, I don't see it as just a building. I see justice.”

Sculpture by Julien Dillens representing Justice between Clemency and Law

This brings us back to the Salle des Pas Perdus. Michel is explaining how the building was conceived by its architect, Joseph Poelaert, who first presented the designs in 1861, some 22 years before it would be completed. “This is one of my favourite places in the building,” he says. “Because it's here you can understand Poelaert’s purpose. He wanted that justice to become a symbol of strength. To show the strength of justice, but also the people.”

That pride in the building has not always been shared by his peers. In 2010, when Belgium held the EU’s rotating presidency, it launched a competition to collect ideas for repurposing the Palace of Justice entitled, Brussels Court House: Imagine the future! Some of them were outlandish, like turning it into a commercial complex featuring shops, hotels and cinemas. The winner suggested pulling it down completely and starting anew. But in the face of fierce resistance from the judicial sector, the initiative was not pursued. In 2016, the government confirmed that the legal system would remain the sole inhabitant of the palace.

The court of cassation

While some see it as an architectural folly, it is still a working courthouse. Indeed, as Michel chats, lawyers for the Greek former Vice President of the European Parliament, Eva Kaili, are pleading for her to be released from prison with an electronic tag (Michel’s portfolio includes managing buildings like Haren Prison, where Kaili is incarcerated). Other recent cases include those related to the 2016 Brussels bombings and Princess Delphine’s effort to secure a DNA test from her father, the retired King Albert II.

19th century colourised photo

The Palace today

“Anyone who works here can see that it's not adapted. It's not from this time,” says Michel. “A decision was taken some years ago that it was a Palace of Justice and will remain a Palace of Justice. But it's also important to ask ourselves if all that useful space could be more available for the citizens, for the public. So we could maybe use it more often for exhibitions, for example. But the main function of this building is justice and will remain so.”

The once and future house of law

If the plans to repair the Palace of Justice are back on track, it is partly because of those who work there, including barristers and judges. The Fondation Poelaert or Poelaert Stichting, set up by the Bar of Brussels in 2011, has played a crucial role in lobbying government authorities to go faster and further in modernising the law courts.

“We set it up after Belgium had that competition for ideas for reusing the building,” says Jean-Pierre Buyle, who chairs the Fondation Poelaert. “The winner was a scheme to knock it down – and that really annoyed me.”

A former President of the Bar of Brussels and still an active lawyer, Buyle is keen to underline the Palace’s essential vocation as a law court. “Yes, there are problems of floods and falling ceilings, but we can still work very well here,” he says.

The ceiling above the portico

Indeed, he regrets that the trial of the Brussels bombers is currently taking place at the former NATO headquarters in Evere – noting that the trial for the 2015 Paris attackers took place in the city’s Palace of Justice. “Symbolically, the trial should have taken place in the Salle des Pas Perdus,” he says.

Buyle acknowledges the imposing and ostentatious nature of the building but says Belgium was the second richest country in Europe at the time when its first King, Leopold I, ordered its construction. “A dictator has the right to good taste,” he says. “You may like it or not, but it is an incredible building. There is pride, grandeur, solemnity, magic and ritual, all in this one place. When you walk through the Salle de Pas Perdus and into the courtrooms, you know this is a serious place. Shouldn’t we celebrate grandeur, like the Gardens of Babylon or the Pyramids? We should be proud of this extraordinary building.”

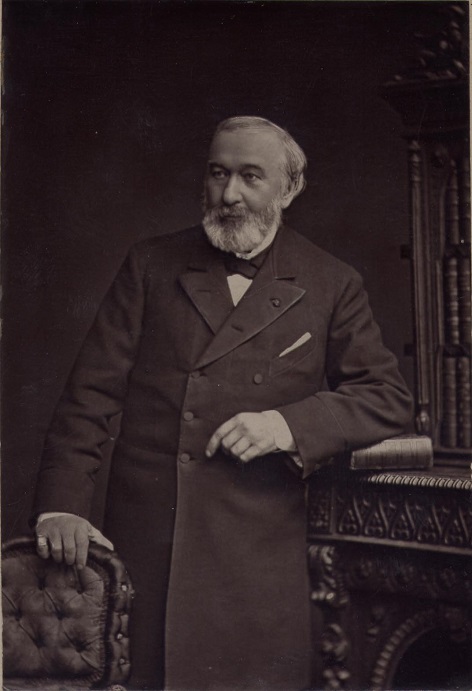

Joseph Poelaert

As proof of its impressive nature, Buyle points out that the Palace of Justice in Lima, Peru, built between 1929 and 1939, is a direct imitation but on a smaller scale and without the gilded dome.

Buyle does not exclude tourist and cultural activities in the building, including a restaurant with a view of the Marolles, a garden on the former oper-air car park between the Place Poelaert and the Rue des Minimes, and even a ski slope on the ramps. “But the idea of a shopping centre was idiotic– not least because there is no longer any commercial perspective for such places in the centre, which they are now mostly out-of-town,” he says.

Architect for nascent nation

The history of the building is an epic story in itself. The idea of a Palace of Justice was to bring together under one roof all the country’s main legal services, including the Court of Cassation (the highest or supreme court), the Appeals Court, the Assizes Court, the Courts of First Instance, the Military Court, the Court of War, and the courts of the peace and police services. A Royal Decree was published in 1860 and the Justice Minister Victor Tesch organised an international architecture contest for its design. However, after the organising committee rejected the 28 submissions, Tesch turned to Joseph Poelaert, the Brussels chief architect at the time, and – in a possible conflict of interest – a member of the competition commission.

Commissioned in 1861, Poelaert drew up designs for a monumental building on the Mont aux Potences or Galgenberg hill, where convicted criminals were hanged in the Middle Ages (the 16th century physician Vesalius was said to have stolen corpses from there at night). It would tower over the Marolles neighbourhood, and more than 75 homes were demolished to make way for it.

However, most of the plot was bought from two sites. The Merode family owned most of the land at the top of the hill, and they sold it – although the old family mansion was left in place and is now The Merode club on Place Poulaert. The second plot was bought from the Berlaymont convent, which would move out to Etterbeek. In 1959, the Berlaymont nuns would move again after their home in the current Schuman neighbourhood was earmarked for another landmark building, the headquarters of the European Commission.

Poelaert was already an established architect by then. Born in Brussels in 1817, he trained in Paris and was said to be one of the most brilliant students of Louis Visconti, the architect of the Louvre. He soon became Belgium’s go-to architect with his designs that aimed to make a statement about the nascent nation’s ambitions.

When he won the competition for the construction of the Congress Column in 1849, his 46-metre design was three meters higher than its inspiration, Trajan's Column in Rome (and for good measure two metres higher than Paris’s Vendôme Column). He designed Saint Catherine's Church over the former Port of Brussels in 1854, rebuilt the Royal Theatre of La Monnaie after the 1855 fire, and designed the Church of Our Lady of Laeken in 1854, which is now also the royal crypt.

Workers building the dome

But Poelaert felt the Palace of Justice would be his legacy. The first stone was laid by Leopold I on October 31, 1866, under the supervision of the engineer François Wellens, who was Inspector General of the Ministry of Public Works.

Poelaert designed the entire Palace, from the façade to the details of the furniture, using a total work process that would chime with Art Nouveau architects like Victor Horta and Josef Hoffmann. Horta would be fascinated, writing about his “admiring stupor” of the building. “This is Cyclopean architecture, dreamed up by hands with no awareness of human scale,” he said.

Poelaert would not live to see it completed. He died in 1879 and was buried in Laeken Cemetery, in a grandiose tomb that recalls his final design. By then, his original designs had already been tweaked, raising the dome to almost double the height. His building was inaugurated by Leopold II in October 1883. But he had already left his signature on the Brussels landscape with his new Acropolis.

Classical jumble, industrial pioneer

The inside of the building was no less eclectic than the façade, with symbols from ancient eras scattered around. Along with carved Belgian lions, engraved scales of justice and embossed coats of arms are images of Medusa and other figures from classical legends. Under the central 39-metre portico, at the foot of two huge staircases are larger-than-life-sized statues of the Spartan lawmaker Lycurgus, Athenian orator Demosthenes, Roman statesman Cicero and the Roman jurist Ulpian.

The connection to Greco-Roman Antiquity is also visible in the columns, with Poelaert using seven orders: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, Composite, pre-Corinthian and Palmiform.

The most lavishly decorated courtroom, the Court of Cassation, has a gold-leaf, coffered ceiling, pink stucco Ionic columns running around the edge, and a giant portrait of Philip the Good, the 15th century Duke of Burgundy, who would base his court in Brussels.

View through the portico columns

The total cost of the construction, land and furnishings was somewhere in the region of 45 million gold francs, which was five times the original budget. However, Wellens would argue that the price of 1,500 francs per square metre was still reasonable compared to other constructions at the time, like the Brussels Stock Exchange (1,200), the reconstruction of the Maison du Roi on the Grand Place (2,000), the Pantheon in Paris (3,000) and the Paris Opera (3,600).

Joris Snaet, an architectural historian at KU Leuven, says Poelaart was a pioneer in his use of an iron frame to support the massive stone and marble. The steel structures supporting the floor and the roof beams reflect both Poelaart’s early adoption of innovative industrial building techniques and Belgium’s role as one of the world’s biggest steel producers.

“It was really exceptional,” Snaet says, pointing out that the metal structures are discreetly hidden under the stone and plaster. “His massive use of natural stone was made possible thanks to rail. And his use of iron beams, combining the natural stone and metal to create large spans, was an engineering and architectural masterpiece.”

Snaet says the notion that neighbourhoods were wiped away in the Marolles is exaggerated, but the myth of obliteration emerged as the Palace was built at the same time as the Senne river was covered over, which also involved the razing of houses. Bigger schemes for the surrounding area were scrapped, though. “After the Palace was completed, there were plans for big avenues to run down the hill, but these were abandoned in the face of protests,” Snaet says.

There have been major changes over the years. The two bronze entrance doors, each weighing ten tonnes, were melted down during the First World War to make cannons for the front. Replacements were forged after the war.

While Hitler was said to have been dazzled by the building when he visited Brussels in the First World War – and his chief architect Albert Speer would write about the Palace of Justice as an inspiration for Germania – it did not prevent the retreating Nazis from trying to destroy it. At lunchtime on September 3, 1944, a few hours before Brussels was liberated by the Allies, German soldiers blew up the dome and the basement. The dome crumbled, walls collapsed and interiors were scorched. In the reconstruction, the dome was rebuilt 2.5 metres higher than before.

Lift to the scaffold

As he ends his tour, Matthieu Michel explains that while the Palace of Justice is just one part of his sprawling portfolio, it is the most demanding. “It is not just the time, but the energy needed to fight with administrative regulation,” he says. “It looks simple, but it's really, really complicated to fix.”

But he insists he is undaunted by the monumental task of rehabilitating a colossal construction. To illustrate his point, he leads me to the northwest side of the building, overlooking the Marolles. There is a long staircase leading down some 20 metres to the Rue des Minimes below. “These stairs would be where the condemned people would enter for their trial,” he says, suggesting that those climbing the steps would be filled with a sense of awe and dread. “You have to be humble when you are confronted with this,” he says.

The Palace of Justice in numbers

- Built between 1861 and 1883

- Dimensions: 186 metres long, 177 metres wide, and 116 metres high

- Area: more than 26,000 square metres or 2.6 hectares. By comparison, Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome has an area of 22,000 square metres

- Eight courtyards and 27 large courtrooms, including the Court of First Instance, the Court of Appeals, and the Court of Cassation

- Salle des Pas Perdus: 90 metres long, 40 metres wide and 80 metres from floor to ceiling. Total floor space around 3,600 square metres

- Dome: weight 45 tonnes, height 19 metres (equivalent to a five-storey apartment building), diameter 17.2 metres

The palace jester

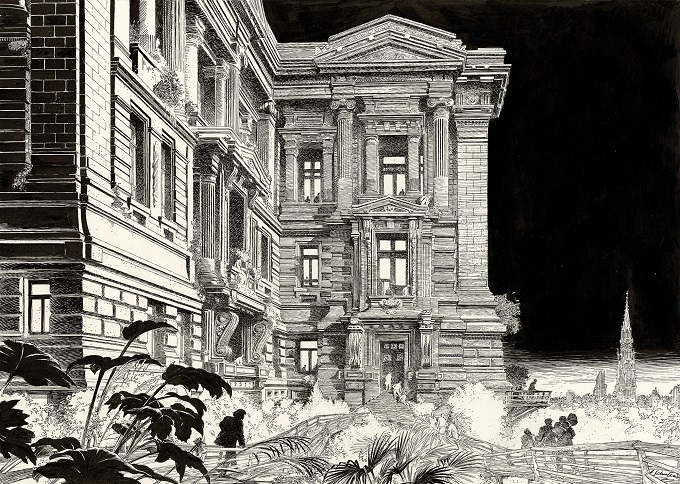

François Schuiten is known for his comic books conjuring worlds that seem familiar yet at the same time are distinctively alien. That includes the signature character in his almost five-decade career, the Palace of Justice, which appears across multiple works.

François Schuiten's many pictures of the palace

“When you are Bruxellois, you cannot ignore it,” he says. “It is huge. Pharaonic. A mise-en-scène more than a building. In fact, the architect, Joseph Poelaert, was more of a director than a designer. It was a theatrical construction for a young country that was building itself, that wanted to show its power to the world.”

Beyond comic books. Schuiten has worked as a production designer on movies like Toto the Hero (Toto le héros), Taxandria and The Golden Compass; designed the Porte de Hal metro station in Brussels; created the interior of the Belgian pavilion at Expo 2005; and led the restoration of the Art Nouveau Maison Autrique.

The Palace is a leitmotiv in Schuiten’s work, notably featuring in his celebrated book, 1992’s Brüsel, co-written with Benoît Peeters. In 2019, he published a new Blake and Mortimer album, The Last Pharaoh (Le dernier Pharaon), which dwells heavily in and around the Palace of Justice.

“Not a single year has passed without me drawing it,” he says. “It is very complicated to draw because it goes beyond proportionality. But when you do, you enter the mind of the architect. And when you get into the details, you see the genius and the madman at work. Poelaert was a megalomaniac.”

Schuiten is a council member of Fondation Poelaert, the group of lawyers, judges, architects and other interested parties that lobby for the building to be restored. “The building still has an extraordinary power,” he says. “Of course, it incarnates something of the past and we have to adapt it to modern times. But that is the challenge: to renew it and bring it into a new era.”

But for all the Palace’s size, and the fascination it exerts on foreigners, Schuiten says most locals don’t notice it anymore. “It’s now in their blind spot. But lawyers and judges use it every day,” he says.