One hundred years ago, French poet and author André Breton published his Surrealist Manifesto in Paris. In it, he defined surrealism as “Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, except from any aesthetic or moral concern.”

In other words, when creating, the only time that the artist will use reason will be when making aesthetic or moral decisions. Other than that, the unconscious, the emotions, and pure thought rule.

How does this translate into works of art? Why did the movement last as long as it did, especially in Belgium? Why did this very intellectual movement capture the general public’s imagination so completely that the names of the most famous of the artists are household words?

This year in Brussels and elsewhere in Belgium, we have an extraordinary opportunity to discover the many facets and artists of the movement as several cultural institutions celebrate the centenary with special exhibitions and events.

Also being celebrated are the 90th anniversary of Jean-Michel Folon’s birth, the 75th anniversary of James Ensor’s death and the 30th anniversary of Paul Delvaux’s death. These milestones all falling in the same year have created intriguing synergies as different museums exchange works of art to offer shows that suggest different answers to those questions.

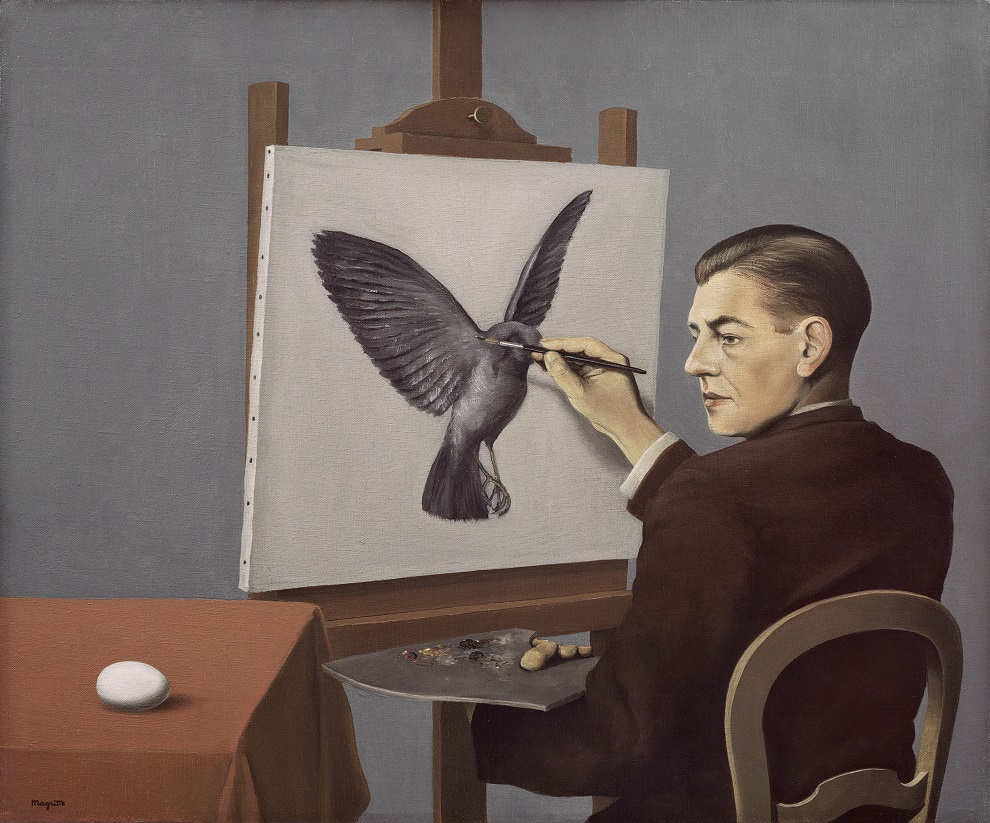

Magritte's Clairvoyance (1936)

The most famous Belgian Surrealists, René Magritte and Paul Delvaux will be well represented but the visitor will have ample opportunity to experience the work of many members of the movement, famous and not so famous.

Royal Museums of Fine Arts Belgium

The august halls of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium is running a show devoted to the movement entitled, Imagine! 100 Years of International Surrealism, until July 21.

Conceived with the Centre Pompidou, the Hamburger Kunsthalle, the Fundacion Mapfré Madrid and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Imagine! features works by Max Ernst, Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró and Man Ray among others. The exhibition is the same in the five cities, but each will add its own specific heritage.

Joan Miro

In Brussels, the show will explore surrealism from a symbolist perspective with the addition of 130 pieces of art including paintings, works on paper, objects, sculptures, assemblages and photographs. Why symbolist art? Because Brussels was the centre of the symbolist movement (1880-1900) which was a precursor to surrealism.

“The key word is the unconscious, the unconscious as the driver of creativity,” says curator Francisca Vandepitte. “Also the unconscious in myths and archetypes so there is a link with psychoanalysis and the imagination; complete freedom of expression. That’s why we used Imagine! for our title.”

Max Ernst - The Fireside Angel (The Triumph of Surrealism)

One result of this freedom is the multiplicity of the media that are used to create art. “We have the object as a trophy and the collages, plastic languages that came from Dadaism but also very precise methods of painting that hark back to the Old Masters,” she says.

Another basic tenet of the surrealist approach is the idea of metamorphosis and the related idea that nothing is created, nothing is lost, and everything is evolving.

One of their favourite devices at the beginning of the movement is automatism, both automatic writing and automatic painting, an ultimate expression of their freed unconscious. “They did however sometimes boost the unconscious by holding hypnosis sessions and engaging in exquisite corpse making,” Vandepitte notes. “An artist would start a drawing then fold it over so the next artist couldn’t see it when he or she added their contribution and so on, chance and the unconscious working together.”

BOZAR

BOZAR’s standout event, running until June 16, is called Histoire de ne pas rire - Surrealism in Belgium, and it covers over 60 years of the Belgian version of the movement and its interactions with others.

Belgium’s home-grown surrealists, including Brussels poet Paul Nougé, went beyond the purely aesthetic in their desire to transform the world with their subversive art. “Surrealism is a state of mind,” says curator Xavier Canonne. “It is not limited to the art one produces. In Belgium that state of mind included not being satisfied with the state of the world, with wanting to change the world through one’s art.”

The title of the show reflects the desire to exorcise the kitsch from Belgian surrealism: the movement is often reduced to a cliché view of Belgium which includes chocolates, fries, beer and even the Smurfs. If one comes across a particularly vivid example of odd bureaucracy or a classic Belgian solution to an everyday problem, the reaction can be “Oh, Belgian surrealism…”

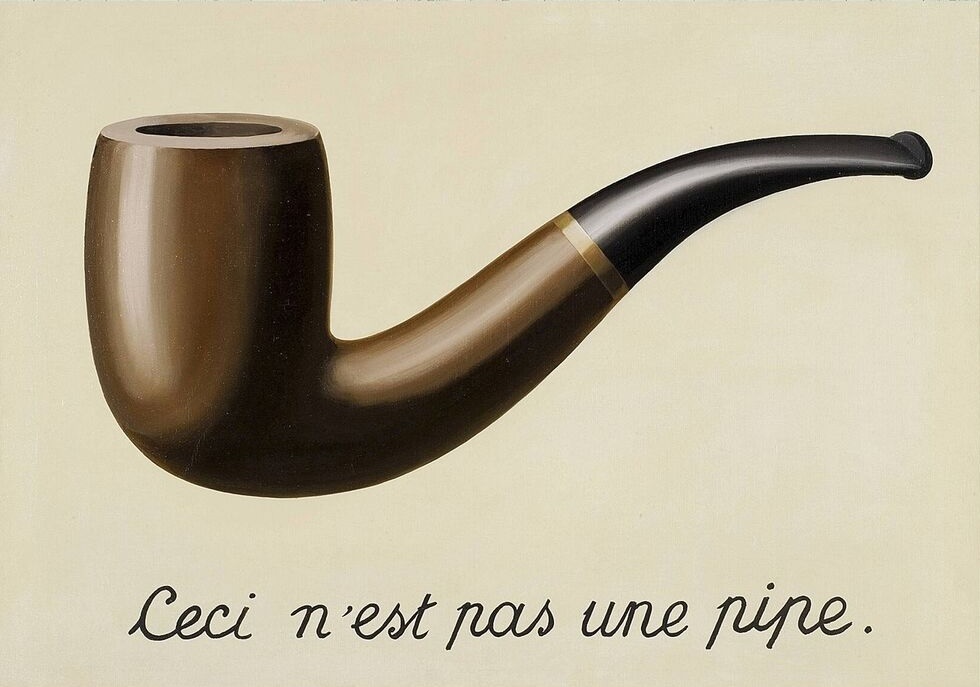

Canonne insists that this is selling the movement very short. “In the 1930s, to write under an image of a pipe, ‘This is not a pipe’ was truly a revolutionary act. It is saying don’t believe what you’re told, don’t believe your eyes, use your independent thought,” he says.

Rene Magritte, La Trahison des Images (1929)

There is humour but Canonne says it goes deeper. “For instance, the image we are using as the show’s poster is the giraffe in the wine glass. At first, one thinks it’s amusing, but then one can have a different reaction, oh my gosh, that poor animal, trapped. Humour was a kind of weapon to change society.”

Surrealism was the longest-lasting artistic movement of the 20th century in Belgium. Well after Magritte and Nougé were no longer on the scene the movement continued for a total of three generations of artists.

The show focuses on international interactions, political-historical background, and important women artists. Included are works by Paul Nougé, René Magritte, Jane Graverol, Marcel Mariën, Rachel Baes, Paul Delvaux Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy and Salvador Dalí

among others. “We have people like Rachel Baes and Jane Graverol who are not well known but are extraordinary painters; it’s a bit like Magritte was the tree that hid the forest. Another aim of the exhibition is to show the originality and the diversity of surrealism in Belgium,” Canonne says.

Paul Delvaux Foundation

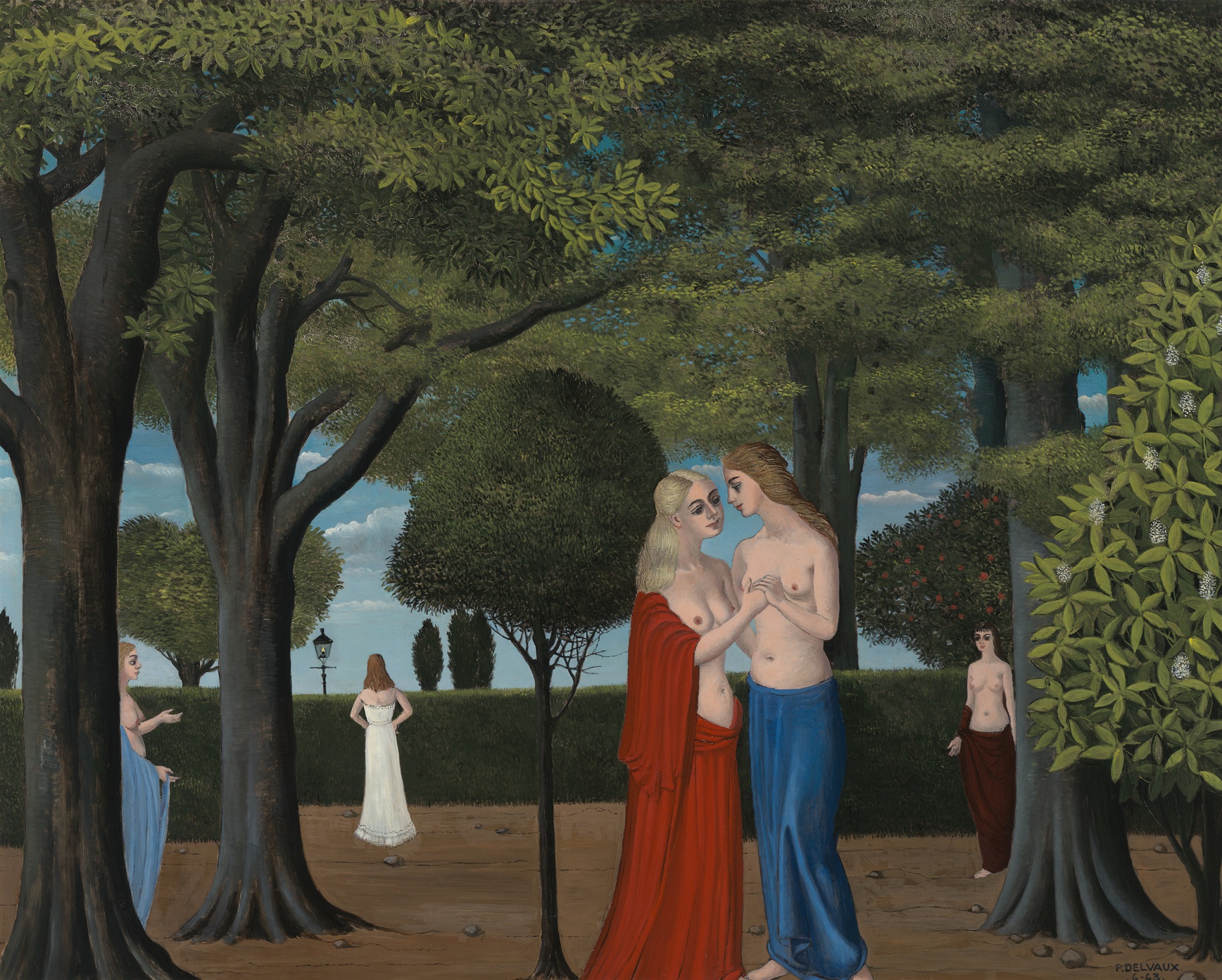

Paul Delvaux liked working alone. He wanted nothing to do with the Surrealist Collective in Brussels, which was committed to effecting social change through their work. He did not even call himself a surrealist. However, he was totally on board with the aesthetic dimensions of the movement.

“He was associated with surrealism because of the poetic universe he creates and the anachronistic mixture of elements,” says Camille Brasseur, Director of the Paul Delvaux Foundation. However his artistic development began when he was taught by the Symbolist painter Jean Delville in the early 1920a. Then in the 1930s, he was influenced by the Flemish Expressionists such as Permeke and De Smet.

Paul Delvaux, Lunar City (1944)

“It isn’t until the 1940s when he discovers the work of Giorgio de Chirico and Magritte. It shocks his system and gives him the impetus to take that next step and start painting his inner world, that he starts to paint as a surrealist. The one thing he kept from his Symbolist beginnings is the monumental scale of his paintings,” Brasseur says.

The Foundation Paul Delvaux Museum in the charming Belgian sea coast village of Sint Idesbald has the largest collection of Delvaux works of art in the world. “We can display such a large number of pieces because we not only have the Foundation’s collection but also, private owners allow us to display items from their collections on a permanent basis,” says Foundation President Pierre Alexis Hocke, who promises that for the centenary, starting on October 24, the foundation will hold, “a very huge exhibition” of Delvaux’s work at La Boverie in Liège.

Folon Foundation

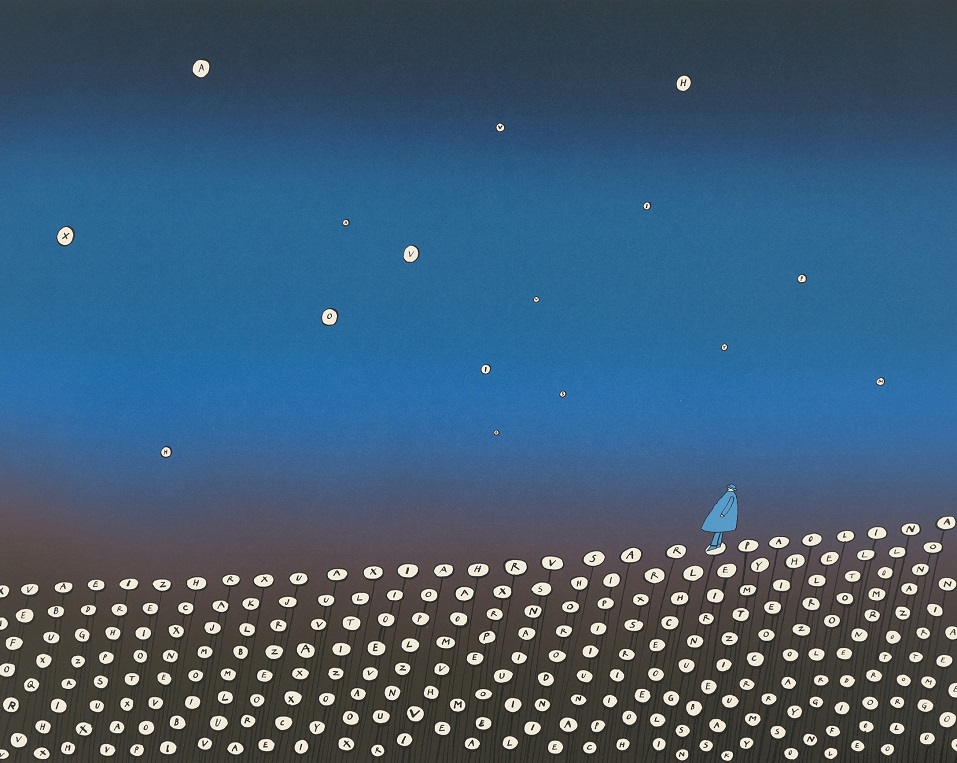

When Jean-Michel Folon was 20 he had an encounter with Magritte’s art which was a revelation that changed the course of his life. The encounter was with the series of murals called le Domaine Enchanté (the Enchanted Realm) that Magritte had just painted for the Knokke Casino.

The young Folon’s reaction: “I thought: ‘You really can do anything in painting. Even invent mysteries.’ That was my first encounter with art.” Though they never met in person, Folon considered him “a father of his generation” especially since it was his exposure to Magritte’s work that put him on a path to an artistic career.

Folon's Je vous écris d'un pay lointain (1972)

The Folon Foundation is celebrating the 90th anniversary of his birth with four events in Brussels under the title, Folon: A Journey in Brussels. The main exhibition takes place at the Magritte Museum, which fortuitously has lent parts of its collection to the other museums putting on Surrealism shows, thus making room for 40 works by Folon to be displayed over three floors to dialogue with works by Magritte.

“There are similarities between their ways of working and their visual vocabularies,” says curator Pauline Loumaye. “They both construct a personal grammar, a personal syntax. They use a large number of synecdoches to have the viewer understand their themes and to communicate their messages.”

The other three exhibitions are, at the Maison Autrique, one of Horta’s earliest houses, a show displaying Folon’s work in various media, watercolour, bronze, ceramic, etching, stained glass and tapestry; at the Design Museum Brussels a show on his collaboration with legendary Italian design company Olivetti; and finally, a Sculptures Walk for which 20 of his monumental sculptures will be displayed across some of downtown Brussels’ most iconic neighbourhoods.

Fell Gallery

To celebrate the Surrealism milestone, Fell Gallery is showcasing until the end of February vintage silver prints by pioneering surrealist photographers Marcel Mariën, Pierre Jahan, Pierre Molinier and Man Ray - displayed alongside contemporary surrealistic prints by Stéphane Fedorowsky and collages created out of antique books by 90-year-old artist Danielle Chanut.

The vibrancy of these elements aims to show that surrealism is alive and well in Brussels even after 100 years.

Fleur en Papier Doré

Magritte (second from right) and friends outside Fleur en Papier Doré

To really get into the spirit of the Surrealists in Brussels after seeing the various exhibitions, there’s no better place than the café La Fleur en Papier Doré at 55 Rue des Alexiens. This was the hangout for René Magritte and his fellow artists for many years. You can’t miss it because a huge black and white photo of the group hangs on the building next to the entrance.

Once inside you will have your breath taken away by the decorations that crowd the walls of the many-roomed café, many of which were created by the surreal bunch - and all of which is protected heritage.

Belgium’s surrealists

Paul Delvaux (1897–1994)

Born in the village of Antheit, between Namur and Liege, Delvaux combined fantastical subjects, hyperrealism, classic academic painting and the unexpected juxtapositions of surrealism in his work. Influenced by the haunting spectres of World War I, his work had recurrent themes: nudes, skeletons, shadows, eroticism, death, desire and horror, typically packaged as an eerie dream.

His fascination with the female form, often depicted with a detached sensuality, became a motif, revealing a preoccupation with the uncanny. Bathed in an otherworldly light, his compositions evoke a sense of suspended time, drawing viewers into a dreamlike realm that transcends conventional reality.

Delvaux’s legacy extends beyond the confines of his canvases, influencing subsequent generations of artists and permeating the cultural zeitgeist. His commitment to the supernatural, coupled with meticulous attention to detail, has left an indelible mark on the trajectory of surrealist art.

Rachel baes (1912–1983)

Born in Ixelles, Rachel baes’ relationship with her father was so fractious that she dropped the capital B from her family name and used the lowercase. In 1929, she exhibited her work at the age of 17 at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris but didn’t start painting in a surrealist style until 1940 at the outbreak of war.

Her paintings often show women in very stylised dresses in odd or disturbing situations such as what seems to be a portrait of Marie-Antoinette with a Mona Lisa-like smile, holding a miniature guillotine with which she is about to cut off one of her fingers.

Jean-Michel Folon (1934-2005)

Folon created a slick surrealism style that was applied to covers of magazines like the New Yorker and Esquire, and poster campaigns for the likes of UNICEF, Amnesty International, Olivetti and Belgium’s former national airline Sabena. Born in Uccle, the son of a paper wholesaler, he initially studied architecture before becoming a graphic designer in the early 1960s, when he visited the United States.

Folon’s designs often feature a plainly dressed Everyman figure with a brimmed hat in an empty landscape. Other works include a vast wall in the Montgomery metro station in Brussels, and illustrations for books by Lewis Carroll, Jean de La Fontaine, Kafka and Ray Bradbury.

Jane Graverol

1905–1984

The daughter of French parents, Ixelles-born Jane Graverol studied at the Brussels Royal School of Fine Arts under symbolist master Jean Delville. Spending time with Magritte and his circle she was an integral part of the development of surrealism in Belgium and cofounded the subversive, anticlerical magazine Les Lèvres nues (The Naked Lips). She came to consider her canvasses as “waking conscious dreams.” After 1960 she changed her focus to flora and fauna and war and violence.

René Magritte (1898-1967)

René Magritte's legacy is a testament to the power of art to challenge, provoke and captivate. His surreal vision, intellectual wit, and meticulous technique have left an indelible mark on the world of art, inspiring generations to question the nature of reality and the limits of representation.

Magritte's paintings invite viewers, into a world where the ordinary becomes extraordinary, and the familiar is rendered mysterious – a legacy that ensures his place as one of the 20th century's most influential and enduring artists. The most famous surrealist quote, “This is not a pipe” is the name of Magritte’s iconic painting depicting a pipe - and sums up what the movement is all about.

An argument can be made that Magritte is the surrealist who has had the biggest impact on high and low culture with his work adapted and plagiarised in advertising, posters, book covers, logos and especially record album covers. Songs, plays and novels have been written and performed based on his Two separate and very different museums are devoted to his work in Brussels.

The international surrealists

Jean Arp (1886–1966)

Born in Strasbourg to a French mother and a German father, he used a surreal tactic to avoid German conscription in World War I: pretending to be mentally ill by crossing himself every time he saw a portrait of Paul von Hindenberg.

Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978)

Son of Greek aristocrats, he studied in Munich and moved to Turin before making a name in Paris with his “metaphysical” art that inspired the new surrealist movement.

Salvador Dali (1904–1989)

The most well-known of the surrealists, Dali was lauded for his precise draughtsmanship, technical skill and bizarre images and subject matter. His talents were far-reaching and included painting, graphic arts, film, sculpture, design, photography, fiction and poetry, and his themes were many including dreams, the subconscious, sexuality, religion and science.

Max Ernst (1891–1976)

Ernst’s first interests were in psychiatry and philosophy but he gave them for painting. He was one of the leading advocates of irrationality in art and the originator of automatism as a current of surrealism. Before that he was a Dadaist, expressing himself through collages and photomontages, creating a scandal in Cologne by staging an art show in a public restroom.

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954)

Polio survivor Kahlo developed her style which consisted of self-portraits mixed with pre-Columbian and Catholic elements. It was sometimes described as naïve surrealism, but she didn’t agree: “They thought I was a surrealist but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality,” she said.

Joan Miró (1893–1983)

Miró's paintings and ceramics often feature whimsical and biomorphic forms, celestial symbols, and vibrant colours. His surrealism was very personal and linked to his bouts of depression, “Without painting, I become very depressed, gloomy and I get black ideas, and I do not know what to do with myself.”

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

Arguably the 20th century’s most influential painter, Picasso’s career is divided into periods, with surrealism in the 1920s, prompting André Breton to announce that “he is one of ours.” Mastered of many styles, he was sometimes accused of stealing other artist’s ideas. His reaction was “Good artists copy; great artists steal.”

Man Ray (1890-1976)

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in New York, Man Ray spent most of his career in Paris. He considered himself mainly a painter but he is best known as a pioneering photographer who developed the use of photograms (he called them Rayograms) and solarisation.

Kay Sage (1898–1963)

Sage was a pioneering painter whose surrealism was marked by mysterious and evocative landscapes that hinted at an underlying psychological tension. Born in Albany, New York, she divorced her Italian prince husband to marry Yves Tanguy, but his death drove her to depression and suicide.

Yves Tanguy (1900–1955)

Born to Breton parents, Tanguy developed a version of surrealism of vast landscapes in muted colours with odd shapes that could be sharp and angular or with a petrified organic look.