Art Nouveau was the brainchild of Belgians like Victor Horta and Paul Hankar who broke with the classical themes weighing down late 19th century architecture. The movement fell out of fashion in the 1950s, brushed away by the brute efficiency of Brusselization. But how should we best appreciate Art Nouveau architecture today?

Brussels has an unenviable reputation: it is a dingy city, both unloved and unlovable, its heritage wrecked by hideous offices and the expressways that serve them. The removal of cars from a vast area in the centre has had some success in luring citizens back to the downtown. Pedestrianisation was accompanied by a campaign to rehabilitate the city’s 19th century central boulevards, and the former Bourse (stock exchange) from the 1860s is now undergoing a near €60m transformation. It will house an attraction themed around beer and a pergola in the form of a giant waffle will perch on the roof.

By placing new layers on old, cycle paths and promenades on traffic-choked streets, new attractions within and atop redundant but valued buildings, the city hopes to vanquish the spectre of Bruxellisation or Brusselization, the phenomenon where anonymous office blocks thoughtlessly replaced beautiful houses.

The city and the wider Brussels region are now reversing that decades-long habit of erasing inconvenient parts of the built environment for the benefit of cars. They are hoping to recover their former reputation – or at least self-image – as a laboratory for excellence in design. Working alongside heritage groups with which they have clashed in the past, both authorities sponsor an annual event, the Brussels Art Nouveau & Art Deco (BANAD) Festival, which organises tours over three weekends in March covering five decades of architecture up to World War II.

The event’s origins lie in grassroots campaigns to protect Brussels’s Art Nouveau past. A few of the visits are in the city centre, wrecked in the minds of many by Brusselization, but most are further afield, and this is your ticket to discover some of the most beguiling and rewarding suburbs of any European capital. BANAD’s logo, the whip symbol, is the one most associated with Art Nouveau and with one architect more than any other, Victor Horta.

Victor Horta’s influence shaped building and design way beyond Art Nouveau’s heyday. But his best-known building in Brussels has not existed for 57 years: the Maison du Peuple (House of the People) which stood below the Sablon, on the edge of the working-class Marolles district. The legacy of its construction at the end of the 19th century and demolition in 1965 can tell the story of how Art Nouveau came to help shape the modern city’s image of itself - and knit it to its suburbs.

The Maison du Peuple was the Brussels branch of a Belgian network of social centres for workers, where the political left focused its activities. The social centres developed in parallel to the department stores that epitomised late 19th century bourgeois consumption culture, offering shopping and services such as cafés (but on a co-operative basis) and a chance to rub shoulders with one’s peers.

The Maison du Peuple in Rue Jospeh Stevens, Grand Sablon, Brussels. Architect Victor Horta. Completed in 1899, demolished 1965.

For the vast Brussels flagship, Horta created a façade rich in iron and glass on a scale to rival the grands magasins, also then adopting this modern look, like Old England (now the Musical Instruments Museum), which opened the same year, 1899. For the workers’ palace, he provided the same level of luxurious detail as for his wealthy private clients, the same ambition to create a single original vision of design.

Instead of sculpted classical details, iron fittings appeared either to emerge from within the masonry or grip onto it like vegetation. Horta’s whip-like motif evoking frozen movement was repeated across the iron balconies and lintels, and sprouted from the stone dressings. This arabesque was even traced by passers-by as the pavement below hugged the building’s irregular, undulating façade.

“Dreadful building”

The wilful omission of historic references in architecture at the turn of the 20th century is known, in English at least, under the umbrella term Art Nouveau. The organic, flowing Art Nouveau practiced by Horta early in his career is its best-known variety, flaunting rather than sublimating the use of iron in construction and emphasising the contrast between materials. The Maison du Peuple is its greatest single martyr.

Why was it destroyed? Because its co-operative owners wanted modern premises. No buyer with a plan to restore and maintain the intricate structure was available and nor was a developer ready to step in. At the time, Brussels was run by Belgium’s central government, which had no policy in place to preserve such a vast and recent building in a style defunct for over half a century. Or the will: “Just leave Horta in peace,” a former minister said. “He’s not worth thinking about. The Maison du Peuple is a dreadful building.”

Already in 1950, a mansion Horta designed at the same time as the Maison du Peuple, the Hôtel Aubecq on Avenue Louise, was demolished. Horta had been dead for just three years by then, and his design for the new Gare Centrale (Central Station) was nearing completion. How could the creations of a still famous and influential architect so intimately associated with Brussels be so disposable?

The Hôtel Aubecq’s destruction prompted a few ripples of local protest among art historians and even some architects (a breed not usually known for their preservation instincts). By the early 1960s, a movement began to form around Jean Delhaye, a former pupil and collaborator of Horta. Delhaye had begun to acquire Horta’s major Brussels townhouses himself in order to protect them, and in 1963, persuaded the Minister for the Arts to protect his master’s 1898 home and studio in Saint-Gilles from demolition. It was the first 19th century building to receive this honour and later became the Horta Museum, of which Delhaye served as the first director.

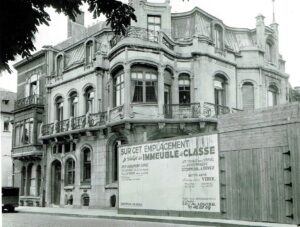

The Hotel Aubecq in Avenue Louise, Brussels. Architect Victor Horta. Completed in 1903, demolished 1950. Credit: Jos Vandenbreeden

Delhaye led the protests against the plans to demolish the Maison du Peuple, but a petition signed by 700 architects from across the world failed to move the Belgian government. The Maison du Peuple’s replacement was an office tower that looked like a monstruous beige mid-digit addressing the city. This gratuitous eviction from the cityscape stirred certain sections of the Brussels public, already uneasy about the legacy of destruction from the 1958 Expo. Exhibitions were organized. The ARAU association, founded in 1969, began motivating citizens to lobby their politicians over the streetscape of Brussels. It organized bus tours and walks that continue to this day.

Horta’s umbrella

In 1971, an influential book by Italian art historian Franco Borsi was published with the assertive title of Brussels, Capital of Art Nouveau, celebrating Horta but also 28 other architects of the same era who had barely been heard of for decades. A combination of local pressure and international oversight meant that during the 70s and 80s, Horta’s major buildings were protected from demolition.

In their wake, works by other largely unknown contemporaries and rivals also received protection. Many of these were in quite a different style, based notably on geometric rather than organic forms. But thanks to their defiance of historic precedents, they too were ushered under the protective umbrella of Art Nouveau as the term slipped out of the textbooks to gain purchase with both the general public and tourists.

View from the inside of Hotel Hannon in Saint-Gilles. Architect Jules Brunfait designed the building in 1902 for a photographer and engineer at the Solvay company.

In 1989, the creation of the Brussels Capital Region placed responsibility for heritage in the hands of local officials. With Horta’s major creations secured, dozens of their contemporaries were protected by the region in the 1990s (three-quarters of Art Nouveau protective listings date from this period or later).

This turnaround in the treatment by Brussels of a relatively recent part of its built heritage was rewarded in 2000 by the Wagnerian accolade of UNESCO World Heritage listing for four of Horta’s major townhouses, including a pair saved by Delhaye (the Hôtel Tassel, the Hôtel Solvay, the Hôtel Van Eetvelde and Horta’s own house). Thanks to their inclusion under the Art Nouveau umbrella (whose spokes are the major creations of Victor Horta), more such buildings are now protected in the Brussels region than any other style.

But beneath that umbrella, what is the Art Nouveau style (or Jugendstil, Liberty, Secession or Tiffany, depending on your location, language or interpretation)?

The term is usually traced back to a Belgian journal of the 1880s describing the work of Les Vingt, a group of artists and sculptors there is sadly (or mercifully) no room to discuss here. Or it may have been inspired by a shop of that name selling modern art that opened in Paris in 1895. The interior of that shop was designed by the Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, who, alongside Horta and Paul Hankar is usually named as one of the three ‘inventors’ of Belgian Art Nouveau.

The hotel Albert Ciamberlani in rue Defacqz, Ixelles. Architect Paul Hankar, 1897 for the symbolist painter who gave his name to the building. Behind, on the same plot, with its facade on rue Paul Emile Janson, Hankar built another large mansion for the painter's brother.

A pioneering exhibition on 20th century design at the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1958 confidently defined Art Nouveau as a movement that existed between 1893 and 1910, and as a style that is “richly curvilinear and dependent on organic forms”. Also writing in the 1950s, Nikolaus Pevsner, still a popular reference for architecture in Britain at least, called the Art Nouveau style a “blind alley” characterised by “sinuosity” and “drifting curves”. These he regarded as straight borrows from English designers Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo and Charles Voysey, whom “the continent” trailed by a decade (he was especially irritated by Horta’s denial of an assumed debt to England).

The definition of Art Nouveau as early Horta is swallowed by the dictionaries to this day: “a style of art and decoration that uses curling lines and plant and flower shapes” (Cambridge).

Crucially, while Moma’s timeline and Pevsner’s definition might fit Horta’s best-known period of activity, they do not work for Paul Hankar or his followers. Their geometric rather than plant-inspired forms were more akin to work of the Viennese Secession than England, with production continuing until 1914 and resuming in a similar, if simpler, vein after the war. They do not work for Henry van de Velde either, who left to plough his own furrow in Weimar in 1899, later co-founding the Deutscher Werkbund, the opposite of a blind alley.

How did the Brussels architects around the turn of the 20th century see themselves? Not as Art Nouveau – the words did not appear on their cartes de visite – and rarely as followers of Horta. So if Brussels Art Nouveau is not just about whips, curlicues and sensuous flowing lines, what is it?

‘A national style for the young nation’

Baedeker’s 1894 guide to Belgium, researched the year MoMA’s period of reference for art nouveau started, summed up the look of the buildings of Brussels thus:

“In architecture, the Gallic proclivities of the people are shown by the overwhelming number of houses in the so-called French Renaissance style (from Louis XIII to Louis XVI) which have sprung up within the last few years and completely altered the appearance of the old Brabant capital. It must be mentioned on the other hand that the Flemish Renaissance style of the 16th century has also become extremely popular, and has been followed not only in private houses, in which the most striking feature is the small proportion borne by the breadth to the height, but also in various public edifices.”

Writing then, as your The Brussels Times correspondent does now, from “personal observation,” Baedeker’s editor was struck by the competing siren calls of historic French and historic vernacular style on the prosperous bourgeoisie, as they chose what statement they wished their narrow frontage to make to passers-by and visitors.

Belgium began the second half of the 19th century as a young and prosperous nation, assembled in 1830 from a bilingual and bi-cultural former outpost of the Habsburg empire. By the time of the 1894 guide, its natural resources alone had helped place it among Europe’s leading industrial economies.

From the early 1890s, these resources were joined by those extracted from King Leopold II’s Congo enterprise. Even more money flowed into the capital, attracting new inhabitants and creating a boom in consumption. Vast numbers of new houses were needed for both the surge in population and to meet demand from existing residents now in a position to upgrade their accommodation.

A major expansion of the city beyond its historic limits followed, much of it following an existing plan from the 1860s, dividing the Brussels hinterland into distinct zones ready to receive different social classes. This directed the newly-wealthy middle-classes into the eastern and southern suburbs of the city, curving around the existing upper-class Quartier Léopold (now EU Quarter) south towards the upper slopes of Saint-Gilles and east towards the Bois de la Cambre.

As before, most chose to build houses in prestigious historic styles of France and the Low Countries – or both and much more at once, the so-called Eclectic style, which received its own inaugural festival in 2021. As the 1890s progressed however, a growing number of intellectual professions (lawyers, academics, artists and liberal industrialists, especially those sympathising with the socialist movement) opted for accommodation bringing a distinctively Brussels touch to the cosmopolitan ‘new art’ taking hold among their peers across Europe.

The ‘New Belgian’ style

By 1910, the end of MoMA’s reference period, Baedeker’s man was able to report the following:

“Since the closing decade of last century, a band of younger architects has appeared who, developing suggestions originally obtained from England, have become the first Continental architects to found, in connection with a new industrial art, an entirely modern architecture, quite independent of all previous styles. Their leaders are Paul Hankar and Victor Horta, builder of the Maison du Peuple. Henri van de Velde, an adherent of the same school, has had to seek in Germany an adequate field for his activity.”

Maison Saint-Cyr, Square Ambiorix, 1903, architect Gustave Strauven.

Crucially, the guide said “this 'New Belgian' style is commonest in the suburbs of Brussels”, and there it remains on the eastern flank of Brussels proper. The most impressive survivals are dotted parsimoniously across commercial Schaerbeek and the administrative and military dormitories of the Quartier des Squares (the Squares District) in Etterbeek, scattered or in clumps over the more sensuous southern regions of Ixelles and Saint-Gilles.

The ‘New Belgian’ style is the flowing lines and the whip of Horta. But it is also the angular, jacked-up bow windows and minimalism of his student Antoine Pompe (who did not even regard his teacher as a proper architect). It is the geometric puzzles of Paul Hankar (Pompe’s “real master”). It is the shields, grooves and lozenges of Hankar’s student Paul Hamesse and the restless urban cottages of Hamesse’s student, Adrien Blomme. It is written across the façades of the 250 or more houses of this period already listed for protection by the region. The Sint-Lukasarchief, an archive of architecture in the region founded in 1968, estimates their number at 2,500.

The banal beauty of Brussels suburbs

Art Nouveau in Paris, Vienna and Barcelona tends to be found in public buildings and infrastructure, vast apartment buildings, department stores and prestigious villas. Meanwhile, in Brussels this somewhat undefinable style born of elites thumbing their noses at the dead weight of historicism made its way down the social scale, adorning the narrow, terraced houses of the humblest clerks, be it only in the form of a modest sgraffito or doorknocker.

The most recent Art Nouveau building to receive protection in the Brussels region is the 1902 house built by architect Frans Hemelsoet for himself in the northern wastes of Schaerbeek. Announcing the decision, the region’s minister in charge of Urbanism and Heritage, Pascal Smet commented: “The Hemelsoet house is of a banal kind of beauty for Brussels. You could easily not notice it."

He is right. Such houses are myriad in the avenues and side streets of Ixelles, Saint-Gilles, Schaerbeek and beyond (see box with the top Ixelles addresses). The attention to detail and the quality of the materials with which they were built match their gleeful indifference to the appearance and scale of their neighbours. The advice of the 1910 Baedeker guide still stands: to discover the real glory of Brussels, hit the suburbs and seek out the New Belgian style.

| Here is a selection of some of the best examples of Art Nouveau architecture, all in the commune of Ixelles: · Rue de Livourne 83. 1912, art nouveau with eclectic elements. Architect Octave Van Rysselberghe for himself · Rue Faider 83. 1900. Architect Albert Roosenboom. Sgraffites by Privat Livemont · Rue Simonis 64. 1891, early art nouveau. Architect Paul Hankar · Rue du Châtelain 63. 1903, geometric art nouveau. Architect Georges Hobé. Sgraffites by Paul Cauchie. 65 also by Hobé in the same style · Avenue Louise 224. Hôtel Solvay, 1894 by Victor Horta · Rue Dautzenberg 11-13. 1911, geometric art nouveau. Architect N Klein · Rue Van Elewyck 41, 43, 45. Three art nouveau houses, 1902 by Aimable Delune · Rue des Champs Elysées 72. 1908, geometric art nouveau. Architect Paul Hamesse · Rue des Champs Elysées 6. 1906 geometic art nouveau conversion of an older house. Architect Paul Hamesse · Chaussée d'Ixelles 95-97. 1905 art nouveau apartment block. Architect Charles Patris · Crossroad of Rues Saint-Boniface and Ernest Solvay. 1900-1901, group of 11 art nouveau houses. Architect Ernest Blérot · Rue Ernest Solvay 32. 1904, geometric art nouveau. Architect Victor Taelemans for himself |