After years of closure and then as a building site, the wraps came off the former Brussels Bourse on September 9, as its doors were flung open to the public.

The main attraction here is Belgian Beer World, an interactive journey through the history of the brewing process which spirals through the upper floors of the building and culminates in a glass of the stuff on a new roof terrace with views over the Grand Place.

Far below, those coming to or from the Grand Place meanwhile can walk through the old trading floor, pausing for a coffee, or a meal or just sit on a bench to admire the restored 19th-century interior and wonder which bits are by Rodin.

Under the former stock exchange, the remains of one of its predecessors on the site, a 13th-century Franciscan monastery, can be visited and, facing Place de la Bourse, the wide flight of steps at the main entrance has resumed its role as a free terrace. With attractions on its roof and in its basement as well as the beer museum and providing a covered passage and an amphitheatre from which to observe the theatre of public life, it’s a Swiss army knife of a building.

The Bourse sits roughly midway up the now car-free Boulevard Anspach for which it was intended to provide a centrepiece when it and the street were planned in the 1860s.

As tourists and locals took their seats on the grand staircase that unseasonably warm autumn evening of opening day, the pedestrian zone appeared finally to come together. Above all, there was an atmosphere of good humour, that indispensable suit of armour to make life in Brussels bearable.

It will be needed in the years to come, as the central boulevard will be a building site until the end of the decade. To the north, huge transformations are underway or about to start on three sides of Place de Brouckère.

To the south, the Palais du Midi looks set to be demolished as part of the new metro line. And on most of the block diagonally opposite the steps, the former Grands Magasins de la Bourse department store will make way for the new Dome complex of shops and homes.

It’s not all smiles on the piétonnier however. When the plan to create what Brussels claims is Europe’s largest car-free zone was firmed up in 2015, traders claimed their businesses would be destroyed, that it would be simultaneously deserted and violent after nightfall, and that an army of the homeless would occupy the street.

Related News

- The meaning of Brusselization

- The grand plans for the Cinquantenaire

- How Art Nouveau was invented in Brussels

Since completion in 2021 these early warnings have been replaced by complaints about an excess of low-quality fast-food outlets, the uneasy cohabitation of leisurely strollers with whizzing scooters and frequent privatisation of parts of a newly-conquered public space for sometimes noisy events. With such objections at hand, citizen associations argue that the pedestrianisation scheme has prioritised visitors over residents.

A hangover of excess tourism

“Brussels, it must be said, is not the greatest of cities for venturing,” American travel writer Bill Bryson wrote 32 years ago in Neither Here Nor There. “Once you've done a couple of circuits of the Grand Place and looked politely in the windows of one or two of the many thousands of shops selling chocolates or lace (and they appear to sell nothing else in Brussels), you begin to find yourself glancing at your watch and wondering if nine-forty-seven in the morning is too early to start drinking.”

Brussels knows this image persists at home and abroad, despite the removal of the traffic from the central boulevards. As the 2015 launch document for the Bourse project showed, the plan is to coax tourists and out-of-towners through the building and out into the piétonnier and beyond rather than circling back to the Grand Place and Ilot Sacré and waiting for the sun to dip below the yard arm.

This strategy has led Inter-Environnement Bruxelles (IEB), a federation of pressure groups from across the region and the heritage and planning association Arau (City, Urban Research and Action Workshop) to file an appeal with the Conseil d’État (Belgium’s highest administrative court) to cancel the permit for Belgian Beer World, the very centrepiece of the plan.

They warn that this policy of extending the tourist zone to the pedestrian area and towards neighbourhoods further west, in short of improving the “attractiveness” of the downtown, threatens the habitability of the zone for residents.

Arau complained of “damage to a listed monument and the folklorisation of the historic centre of Brussels” and while it and IEB welcomed the restoration of the Bourse, “this emblematic building deserves better” than becoming a tourist attraction, they said. In a statement titled ‘Watch out for the Hangover of Excess Tourism’, they warn that Brussels risks becoming a new Bruges, Barcelona or even Venice.

Murky origins

Any prospect of Brussels joining Europe’s Venices however disappeared in the 19th century when the city authorities decided to cover up the river Senne that snaked its way through the centre. Long abandoned as a means of transport, the problem of the Senne, prone to floods and viewed as a source of disease, had for decades preoccupied Brussels planners with schemes to roof over or divert it.

Covering the Senne river

Inspired by Haussmann’s transformation of Paris then underway, a new young mayor appointed in 1863, Jules Anspach (wags referred to him as Ansmann), became convinced, with the help of unscrupulous English businessmen, that an important modern city deserved a far more ambitious solution. Brussels should not just bury its river but replace it with a splendid new commercial centre along a stone backbone of wide streets emulating the much more prosperous French capital.

Four new boulevards bisecting the historic centre of Brussels from south to north were built over the period 1867-71: Hainaut leading to Place Fontainas, then Central, leading to Place de Brouckère, where, in the form of an elongated tuning fork, the parallel Boulevards de la Senne and du Nord led to the edge of the downtown.

They are now named after three former mayors and a city alderman: three unjustly imprisoned (Adolphe Max, Charles Lemonnier and Émile Jacqmain, all during the First World War) and one after the man who built them, who, in the view of certain contemporaries, should have been.

Anspach’s plan, designed to be self-financing as rising land values along the former course of the malodorous Senne paid for the upfront investments, soon fell apart in its own stench of corruption and mismanagement.

Boulevard Anspach, the central stretch of the scheme now occupied by the pedestrian zone, was designed to host three monuments: a great fountain at an octagonal Place Fontainas, a vast covered market fronted by a mini-square on the west side near Place de Brouckère, and the Bourse itself.

An English company created for the purpose, the Belgian Public Works Company was awarded a contract to build them and cover the river in a culvert flanked by sewer pipes. At its head was a corrupt MP, Frederick Doulton, of the famous British industrialist family of the same name (and maker of sewer pipes for cities).

Thanks perhaps to his British connections, the company appointed a Belgian artist, Louis Ghémar, to produce a ‘making-of’ for the works. Having made his name with photographs of the funeral of Belgium’s first King, Léopold I, and of Queen Victoria in mourning, he now recorded the burial of the river Senne in a series of images.

An elite society portraitist and now corporate artist, Ghémar was also a satirist who would become a figurehead for the peculiarly Brussels brand of humour known as zwanze. Based curiously in Anspach’s birthplace in Rue de l’Éveque (it is now a restaurant called Chez Jules), he held a series of annual ‘fantasy exhibitions’ of fake works by respected rivals, mocking the same official art scene he now swam in himself.

The 1870 edition took place in a wooden pop-up hut placed in the midst of the boulevard under construction. According to the exhibition catalogue, Room T (Salle T or saleté, meaning dirtiness in French) could be found underground in the sewer. Room O (Salle O or salaud, bastard in French) meanwhile included the work ‘Triptych to be Hung in the Gothic Chamber of the Town Hall’ (Tryptique destiné à la salle Gothique de l'Hôtel de Ville).

Louis Ghémar 'Tryptique to be Hung in the Gothic Chamber of the Town Hall’

This depicted on its three panels a manic Mr Punch before an easel, the Senne being built over and, in gorgeous robes, a kneeling Anspach, ‘The cleansing mayor with a halo of a martyr or a saint, at your discretion’ (le bourgmestre assainissour avec l'auréole du martyr ou celle de canonisé, au choix). A version in oil paint is in the Brussels City collection.

Lost illusions

After his premature death, Ghémar’s work was carried on sporadically at a series of ‘Great Zwans Exhibitions’. While there is no fixed definition or spelling of the word, "zwanze makes you think after making you laugh,” according to an organiser of one of these. It’s not hard to guess what Ghémar was getting at with his Anspach triptych: the corruption and clownish incompetence that were already the subject of an anonymous book ‘The Anspach Question’ published in 1868.

In early 1871, news arrived from London of the liquidation of the Belgian Public Works Company, four years into its contract with the city. All in a cloud of reports of embezzlement and bribes that ended in court, where the judgments spared neither the BPWC nor the city.

The scheme was drastically cut back and two of the three planned monuments were dropped: there would be no fountain at Fontainas and the market was scaled back to half the planned size and demoted to a backstreet location (the new city hall, Brucity, occupies its footprint).

A Parisian contractor was engaged to rescue Anspach’s Paris-on-Senne (literally) scheme, but it too collapsed after four years. Cash prizes for the best façades and soft loans from the city encouraged local investors to fill in most of the gaps by 1880.

The narrowness of the new boulevard, however, squeezed between the canal port and the sacred Grand Place, had ruled out the planting of large trees to alleviate the stone corridor or any generously-sized apartments around courtyards as in Paris.

The Brussels bourgeoise declined to take up residence and a sharp decline in the real-estate market left most of the new blocks in the hands of the city (where many of them remain) and at a loss.

In a sentimental 1888 account of his homeland, La Belgique, novelist Camille Lemonnier commented that the new boulevards gave “the image of a display of ease that's perhaps more apparent than real” and contrasted “the rich, heavy architecture with the vacant stores on the ground floor… [and] the desolation of the upper floors, at whose windows an infinity of yellowed signs offer flats to rent.”

The Bourse in 1890, when horse-drawn trams ran down Boulevard Anspach

As the promised returns failed to arrive, debt per inhabitant in Brussels increased eightfold over the period 1860-1880. Yet like the river, Anspach’s role in this débâcle was covered up and his memory was cleansed with a lavish 1897 memorial fountain on Place de Brouckère on the site of the church of the Augustins that he’d promised to protect (fragments of both church and monument survive elsewhere in Brussels).

Place de Brouckère at the turn of the century

Extensive enough to erase much of the character of the old city but not ambitious enough to transform Brussels’ economy, the new boulevards would instead track the wider city’s underlying fortunes, a process that continues to this day. Initially, they struggled to compete with the established shopping centred on Rue de la Madeleine next to the Grand Place, where the luxury goods sector had been rooted since the 18th century.

But as the first stirrings of the mass-consumer economy arose during the recovery of the 1890s, the boulevard appeared to deliver on Anspach’s promises, in commercial if not residential terms. The restaurants, tobacconists, bootmakers and confectioners of the early years were joined by traders selling recognisably modern technology and services.

In the early years of the 20th century, Boulevard Anspach began to pull ahead of Madeleine with its cramped, converted old houses, thanks to purpose-built, modular retail units with step-free access. As frequent number changes show in business directories, these could be knocked through to shape themselves around new gadgets and services as they arose amid the arrival of electricity and wider discretionary spending.

Belle Époque

Postcards from just before World War One show scenes teeming with life as strollers shared the breadth of the road with carriages, trams, bicycles and occasional cars with a degree of equity hard to imagine today. They could slip between trams to reach shops selling novelties such as typewriters, telephones, light bulbs and phonographs, early record players often referred to as ‘talking machines’.

French audiovisual giant Pathé had no fewer than three large sites on the west side of Boulevard Anspach. From early morning till 11pm daily, shoppers could wander in and listen to ‘recordings of the world’s greatest celebrities’ at no charge at the Pathé-Concert, then succumb to impulse and buy the disk and a player at the company’s shop next door.

In the space of the generation the boulevard had existed, shopping had become a pastime in itself for the general public. A new concept of browsing for pleasure to see what novelties were on offer instead of just the chore of fetching age-old commodities from specialized suppliers.

This new habit had entered Brussels culture through the arrival of department stores, which numbered three in the street by 1910. But the shallow plots bequeathed by the boulevard scheme from an already-vanished age hindered the expansion they required to compete with the behemoths of Rue Neuve.

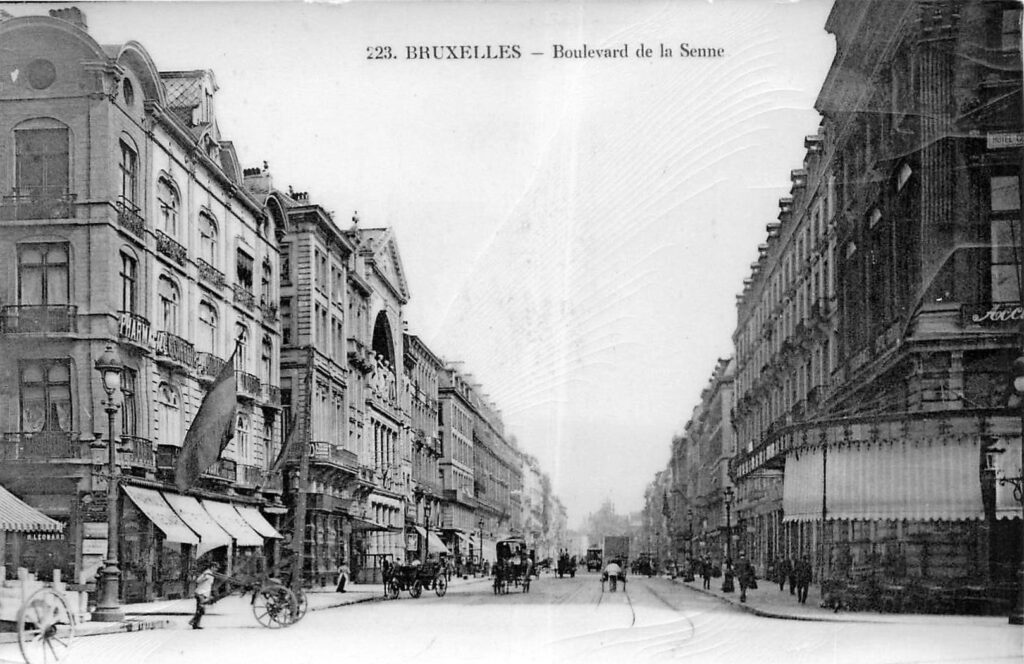

The Boulevard de la Senne (now Boulevard Émile Jacqmain)

In 1913, on the site of the Grands Magasins du Centre, Pathé opened its Palace cinema, in a late Art Nouveau style by Paul Hamesse. An early example of Boulevard Anspach bowing to its vocation of leisure and spectacle rather than utility, a 2,500-seat auditorium sat atop a vast underground bar.

Quenching thirst had become a key role for the street: a score of brasseries serving domestic fayre rubbed shoulders with port-tasting house The Splendid, a branch of the Central Tienda Spanish wine-bar chain and the Select Company bar américain. This crowded scene led to the innovative ground floor loggia terrace of the Café Sésino, a covered space within the structure of the building sparing drinkers and passers-by a tussle over pavement rights.

By 1930, “tempting shops, cafés and restaurants succeed each other in an almost unbroken succession. In the evening, these boulevards are the rendezvous of the inhabitants of the neighbouring quarters", Baedeker’s guide to Belgium & Luxembourg informed visitors.

Despite the Parisian pretensions of their facades, the festive (and noisy) Boulevard Anspach’s cramped apartments had failed to lure the well-heeled tenants they were designed for. Instead, offices moved into the upper stories of these stone buildings, processing the sales of the retail units below or hosting services on a scale undreamt of in 1867.

On the key stretch between de Brouckère and the Bourse alone were branches of the British Great Eastern Railway, the Norddeutscher Lloyd shipping company, The Yorkshire Insurance Company and Crédit Lyonnais. Business information company Dun & Bradstreet set up shop overlooking the stock exchange above the Monico Bourse café.

The wrecking ball

As Boulevard Anspach approached its centenary in the 1960s, it continued to track the fads and fortunes of the city. Poorly maintained and with most of its width given over to cars, its Belle Époque appeal for strollers had long since evaporated. The enormous Pathé Palace, unprofitable and unable to compete with TV and younger competitors, was on its last legs (soon its auditorium would become a car park).

In the last decade of Belgium’s trente glorieuses, employment and infrastructure took precedence over crumbling heritage. Another audiovisual giant, Dutch this time, Philips, with a factory at the south end of Boulevard Anspach behind Place Fontainas, decided to build its Belgian corporate HQ at the north end of the street.

Place de Brouckère, 1961

Completed in 1969, the 63-metre tower, which swept away the Café Sésino and its indoor/outdoor terrace, was soon joined opposite by the city’s administrative centre, the same height and with the same stealth-bomber functionalist looks.

Seen from above, these two mammoth sentinels at the gateway to the boulevard, built in the shape of the letters X and H, a never-explained acronym, seemed set to usher in the wholesale destruction of Anspach’s scheme.

In the mid-1970s the Grand Hôtel of 1875, next to the Philips tower, was demolished and, with the Senne finally diverted to the west of the city, trams were sent downstairs to run through the culverts built by the Belgian Public Works Company. Along Boulevard Anspach, the car reigned supreme.

Boulevard Anspach in the 1980s

Yet because of, or if you prefer, thanks to, the oil shock, that wholesale destruction didn’t happen. The boulevard, like the uncompleted metro project beneath it, remained petrified for 40 years.

Awakening

The fate of this car-first, 1970s version of Boulevard Anspach was sealed in 2012. A series of guerrilla protest-picnics blocking the road organised by the philosopher Philippe Van Parijs set the urbanism machine whirring again.

Marking the 10th anniversary of the successful snack mob, Van Parijs wrote in The Brussels Times in language that already feels of another age: “The Facebook generation did its job. Thousands of people announced their presence, and on June 10, 2012, a giant picnic took place on the Place de la Bourse and shook Brussels’ political parties out of their lethargy. In the weeks leading up to the municipal elections of October 2012, most of them came up with proposals to make Boulevard Anspach, until then a four-lane urban motorway, more or less car-free.”

On June 29, 2015, concrete blocks were heaved into place, creating a de facto pedestrian zone along much of Boulevard Anspach. Five years later in September 2020, the city announced that the façade-to-façade building work was “almost finished” and grumbling about the pedestrian zone succeeded the grumbling about the lack of a pedestrian zone.

Much of the grumbling has centred on the number of fast-food joints. But for centuries Brusseleirs have been known as kiekenfretters (chicken-gobblers), and snacking is baked into the city’s identity. Besides, the burger and kebab shops (and the chicken shops) predate pedestrianization. All that’s changed is the snacks can be gobbled while dodging electric scooters instead of cars.

Footfall, then windfall

Since its birth, Boulevard Anspach has reflected the changing fortunes and tastes of the city, and the downtown ‘Pentagon’ area of 2020s Brussels is not rich. If there are many fast-food joints in the street, it’s perhaps because people like them and it’s what they can afford.

Aerial view of the Brussels City's administrative centre, left, and the Philipps offices right

A century ago, Capadocia Kebap at number 40 was a shop selling lace and bonnets. That is now the role of the Passage Saint Hubert, not the Boulevard Anspach of the 2020s.

When work started on the permanent form of the pedestrian zone in 2016, mayor Yvan Mayeur hoped that new apartments would finally lure the middle classes downtown: “Of course, we’re looking at a gentrification of the downtown but one that strengthens its social mix…the locals who come to stroll here don’t always perhaps have the economic means to sustain these businesses.”

The lack of decent affordable housing and essential shopping in the centre is serious, and the politicians are yet to fulfil the promises they made in this respect when planning the pedestrian zone.

But Arau and IEB’s argument that the Bourse should be used to provide public services to underserved locals is not serious, not the least because a gargantuan new city hall opened a few steps away last year. And while Brussels is unlikely to morph into Venice by the end of the decade, the city has spent almost €90m (€7m of it EU recovery money) concentrating tourism where it’s already strong.

Poetic justice

On my visit to Belgian Beer World, it was full of young people spending a warm summer’s day indoors, shrieking with laughter and tugging each other’s arms to point out the next exhibit. A vein of rather forced self-deprecatory humour runs through the museum. The same heavy-handed but recognisable stab at zwanze is in the region’s new official slogan to market itself to the world: ‘Brussels: perfectly imperfect’.

The Bourse today, facing a pedestrianised boulevard

What’s done is done. Perhaps the zwanze master Ghémar should be our guide to the state of the downtown in the mid-2020s. Imagine his glee at a metro line still unfinished after 50 years of rushing people through the ‘Salle T’ of the sewers. Or at the ‘merry tourist’ who broke a statue on the inaugural weekend of a monument rebaptised as a temple to alcohol. How perfectly imperfect.

Boulevard Anspach is finally getting its triptych of monuments. The Bourse has been reborn and the twin towers at its northern gateway are being transformed in the image of the city’s fortunes in the 2020s. Oxy, the former admin centre now superseded by Brucity, will be reclad in gentle fawn tones and host a hotel, apartments and restaurants. The Multi tower has already been encased in a sanitary white overcoat.

For the first time in their half-century of existence, the two buildings won’t have the same façade, elevating the mismatched look of the 2020s coffee shop to the scale of a skyscraper. They may lack poetry but in fact, Multi has an official poem. It’s on the developer Immobel’s website.

It namechecks another triptych: Brel, Angèle and Stromae. It’s gloriously bad. It may not be intentional but if that’s not zwanze, I don’t know what is.