The European Court of Auditors (ECA) have signed off the 2023 EU accounts as giving a true and fair view of the union’s financial position but found that the errors in spending from the EU budget increased significantly in 2023, according to its annual report published on Thursday.

In the previous annual report, ECA was already concerned about an increasing error rate, which at that point was too high, while it continued to single out new risks related to EU funds that have been made available in response to the coronavirus crisis and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. This year ECA also warns that the growing debt places an increasing burden on EU finances.

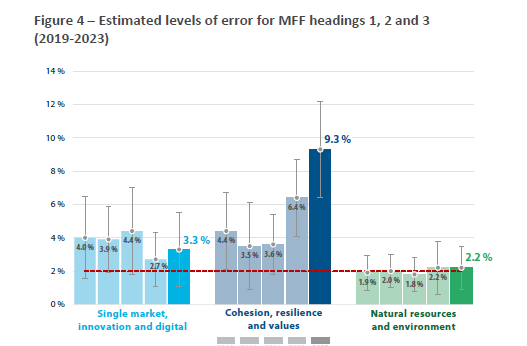

The level of error in spending increased to 5.6 % in the 2023 budget (2022: 4.2 %; 2021: 3.0 %), affecting the €191.2 billion in spending from the EU budget. In addition, irregularities affect a part of the €48.0 billion spent under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), the main pillar of the EU’s pandemic recovery package NextGenerationEU (NGEU).

“As we reach the midpoint of the 2021-2027 financial period, our annual report findings highlight critical challenges facing the EU budget, including high levels of irregular spending”, said ECA President Tony Murphy at an on-line press conference (9 October).

“These challenges underscore the need for robust oversight and accountability structures at both the member state and EU levels in order to maintain public trust and safeguard future EU budgets,” he added. This is the fifth time in a row ECA issued an adverse opinion on the EU’s spending because it concluded that the estimated level of error is material (above 2 %) and pervasive.

Source: ECA

The auditors highlighted that the substantial increase in the estimated error rate is largely driven by the errors found in cohesion expenditure reaching 9.3 % (2022: 6.4 %). Cohesion (including the structural funds), which accounts for 40 % of the budget, is a high-risk spending area.

“Our findings in this area indicate that ineligible costs and projects were major contributors to the estimated error level, as well as infringements of public procurement rules,” the ECA president explained.

He identified several factors that had increased the risk of irregular spending, such as time pressure towards the end of the previous budget period, competition with other EU funds, notably from the RRF, payments made under pandemic conditions (when less controls were carried out by the Member States) and the abrogation of the need of national co-financing during the pandemic.

In ‘'Natural Resources and Environment', where agriculture and rural development account for most of the spending, the overall error rate was estimated at 2.2%. The error levels were not material for direct payments, which represent two thirds of the spending in agriculture, but remained material in rural development, market measures, and other areas.

The error rate remained also material and even increased to 3.3 % (2022: 2.7 %) in single market, innovation and digital which encompasses mostly research and innovation expenditure. Errors in this area include different categories of ineligible costs, in particular related to direct personal and other costs.

The auditors are careful to add that the estimated level of error does not refer to fraud, inefficiency, or waste: it is an estimate of the amount of money that was not used in compliance with EU and national rules. However, in the course of their work the auditors also identified 20 cases of suspected fraud which they reported to the relevant EU authorities.

Commission and ECA - different roles

The European Commission, in its response to the audit, says that it takes note of “ECA’s valuable insights as regards the regularity of the EU budget implementation” but seems to downgrade the severity of the findings, claiming that the errors are “administrative irregularities which do not impact the end-result of a project and are usually recovered or corrected”.

The Commission also states that, “given their different respective roles as external auditor and manager of the EU budget, the two institutions may have differences in their methodologies to assess whether an error has taken place, and to estimate the financial impact of that error”. For an explanation of the differences on estimating the error rate in cohesion, see article about ECA’s review report last July.

It is known that the Commission is at odds with ECA, EU’s external auditor and financial watchdog, about the methodology used to estimate the error rate. This time, the Commission writes that it “continues to stand ready to work closely with the ECA to further align audit methodologies and interpretation of rules”.

Until now, the European Parliament has granted discharge to the Commission despite ECA’s adverse opinion, believing that the overall error rate in EU spending was below 2 % if cohesion funding was excluded. This time the Parliament would have to consider that the overall error rate is likely above 2 % even if cohesion spending would be excluded.

Asked about the upcoming discharge debate in the Parliament, the ECA President replied that ECA is not part of the debate but only contributing to it and providing an input by its annual report. Last year there were Member States that raised concerns about the increasing error rate.

He added that ECA does not accept the Commission’s reasoning that the error rate is decreasing as the controls continue until the end of the programmes (“risk of closure”). The Commission’s own estimate of the error rate for cohesion expenditure, based on an assessment of the individual programmes, ranges from 1.8% to a maximum of 2.8% as a whole (as reflected in the Commission’s Annual Activity Reports).

As regards recovery funding, which contrary to cohesion funding is based on progress in milestones and not incurred costs, ECA did not estimate an error rate. It examined all 23 grant payments to 17 Member States in 2023 and found that a third of them did not comply with the rules and conditions. The auditors therefore issued a qualified opinion on this part of the EU budget.

“We found that 16 milestones or targets concerning seven payments to seven member states (CS, EL, FR, IT, MT, AT, PT) were affected by findings with a financial impact that overall, we consider to be above our material threshold. In addition, we found systems weaknesses, including weak design of milestones and targets, and weaknesses in member states' reporting and controls.”

A senior EU official, who presented the Commission's third Annual Report on the RRF , on Thursday agreed that the total error rate cannot be extrapolated for the RRF because of its special design which has been approved by the Council. The Commission says that the RRF is one of the most audited instruments and that it relies on its own audits and the controls in the Member States.

“We don’t think that there is an assurance gap,” the official said, referring to ECA’s critique. “Even if we would agree with ECA’s interpretation of the rules, we cannot amend the RRF regulation halfway trough in the spending period.” An ex-post evaluation of the RRF is foreseen in 2028.