With their fading parchment and delicate ink, old maps are more than just artefacts. They are whispers from the past, offering us glimpses into the minds of those who charted the unknown.

These maps tell stories of curiosity and courage, where every line drawn was an act of hope and imagination. They teach us about the limits of knowledge and the boundless thirst to transcend those limits, to venture beyond familiar shores into the vast, uncharted seas.

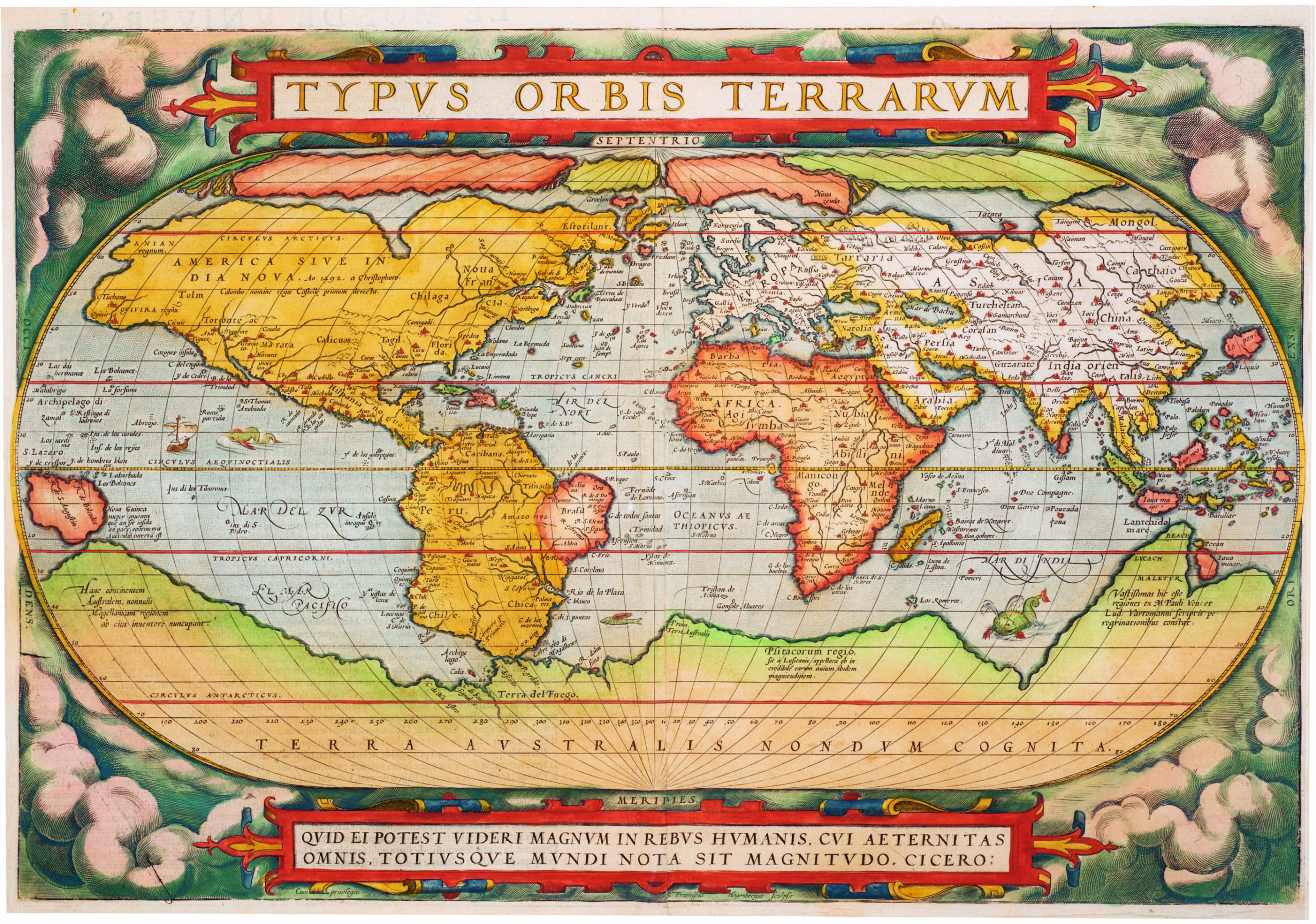

From these charts, we learn the art of seeing the world not as it is, but as it could be. The dragons and sea monsters adorning the edges of the map are no mere decorations. They symbolise the fears and mysteries that once defined the boundaries of human understanding. Yet, they also remind us that exploration is more than physical. It is also intellectual, an endless journey to illuminate the shadows of the unknown.

The images below are from Groundbreakers, a recently published collection of remarkable maps from the Low Countries between 1500 and 1900. They were curated by historian Anne-Rieke van Schaik who immersed herself in the many stories behind the maps, prints, atlases, globes and instruments from the Phoebus Foundation collection.

Friedrich Bernard Werner and Johann Friedrich Probst Brüssel, c.1729 Bird’s-eye panorama of Brussels Hand-coloured copper engraving and etching, 434 x 1134 mm. Credit: Credit: The Phoebus Foundation Antwerp

Friedrich Bernard Werner and Georg Balthasar Probst Antwerpen, c.1729 Panorama of the Antwerp roadstead Copper engraving and etching, 405 x 1100 mm. Credit: The Phoebus Foundation Antwerp

The objects testify to a history containing the never-ending battle against water and the Eighty Years War to colonial expansion and the struggle for Belgian independence.

Antwerp. Credit: The Phoebus Foundation Antwerp

Particular attention is paid to the Southern Netherlands, modern-day Belgium, where maps by 16th-century pioneers like Gerard Mercator and Abraham Ortelius opened up new paths, both literally and figuratively – and even today, provide panoramas of the past.

Triptych of city views of Den Bosch, Leuven and Mechelen in the duchy of Brabant, in Civitates Orbis Terrarum, 1599 city atlas compiled by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg. 's-Hertogenbosch - literally 'the Duke's Forest' - includes immense St John's Cathedral, seat of the archdiocese. Leuven panorama shows the old city walls and the castle and watchtower. Mechelen's Keizershof and Hof van Hoogstraten (two royal residences) stand out while St Rumbold's Church is described as a "very tall and fine tower". Credit: The Phoebus Foundation Antwerp

These old maps reveal that the world is not static but ever-changing, shaped by discovery, conquest and connection. They remind us that our own perceptions, like the maps of yore, are incomplete – mere sketches of a reality far richer and more complex than we can imagine.

Frans Hogenberg Leo Belgicus, 1586 Map of the Low Countries in the shape of a lion Copper engraving, 365 x 495 mm. Credit: The Phoebus Foundation Antwerp

Abraham Ortelius and Frans Hogenberg Typus orbis terrarum, 1570 World map Hand-coloured copper engraving, 340 x 495 mm. Credit: The Phoebus Foundation Antwerp

Hans Collaert and Theodoor Galle after Johannes Stradanus Nova Reperta: Sculptura in aes, c.1590 The invention of copper engraving Copper engraving, 263 x 340 mm. Credit: The Phoebus Foundation Antwerp