Greece celebrates on 25 March the 200th anniversary of The Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman empire. The war, waged by Greek revolutionaries between 1821 and 1830, is a struggle of the highest historical, national and social significance in Greece’s history and the founding event of the modern Greek state.

The preparation of the War of Independence, its long duration, its successful conclusion, its heritage, principles, values, and the realignment of Greek culture along both classical and Western lines, before and during the War, shaped the future of the country.

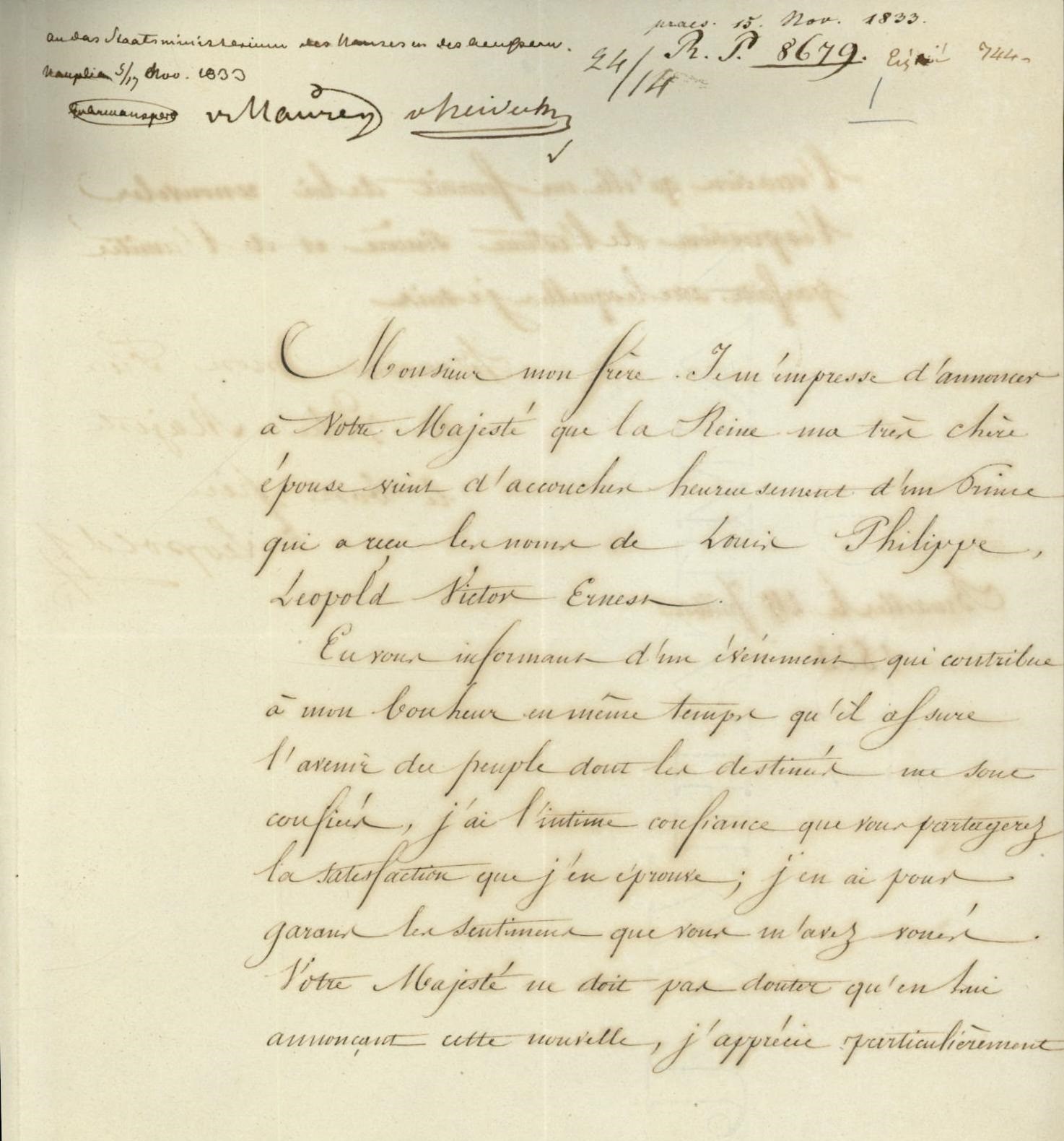

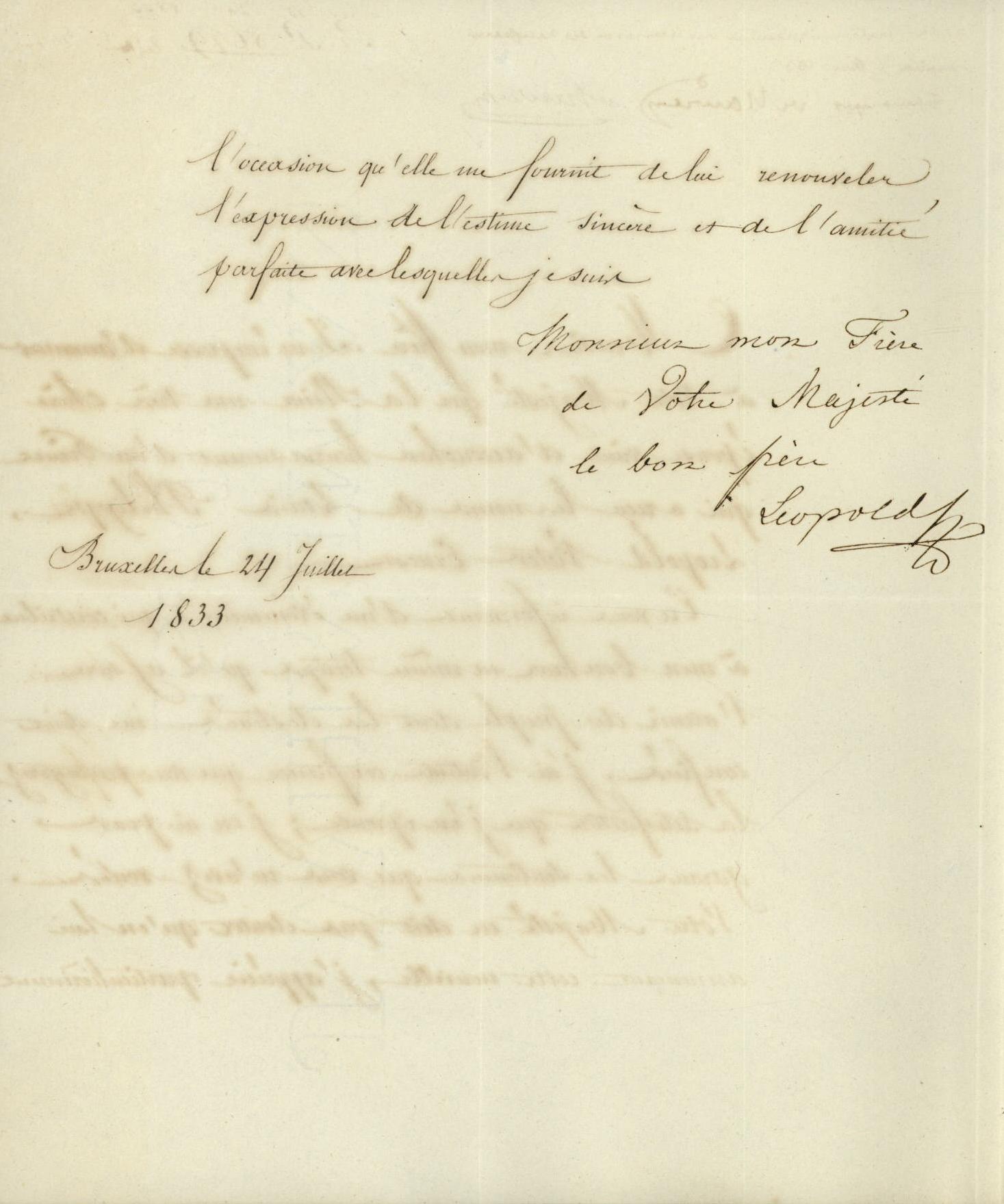

On 24 July 1833, King Leopold of Belgium notified King Othon of Greece of the birth of his son. This is the first recorded communication between the two countries and could be considered as a de facto recognition of Greece.

The roots of the Revolution

The Greek Revolution of 1821 was the closing act to a long line of sporadic but unsuccessful Greek uprisings over the centuries, ever since the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. The positive outcome of the Greek Revolution in 1821 can be attributed to a number of decisive developments, both in the West and in the Ottoman Empire itself.

Firstly, the Revolution benefitted from the gradual emergence of a strong and affluent Greek diaspora, which had seized new opportunities arising from the international setting to achieve an economic revival, based largely on commerce with the West, allowing it to generate the necessary wealth to found schools and libraries, to finance studies at Western European universities, and fund publications in Greek.

Secondly, the Revolution was energized by the Greek intellectual and educational upsurge inspired by Western Renaissance and the Enlightenment, itself boosted by a broad economic revival.

Thirdly, the political, military and economic decline of the Ottoman Empire was decisive for the outcome of the Greek Revolution, as was the new prominence of high-ranking Greeks, especially the Phanariots, in the Ottoman administration by virtue of their education and familiarity with the West.

The letter from King Leopold of Belgium to King Othon of Greece

The rise of national consciousness

The scholars of the so-called modern Greek Enlightenment played a vital role in the education of the Greeks and the emergence of a new national consciousness, especially since the mid-18th century. This movement critically questioned the traditional realities that were dominant in the Ottoman-occupied East, and promoted the new ideas and values of the European Enlightenment, the French Revolution and romantic nationalism. It pushed for change, education and reform and called for a national awakening, while constantly broadening academic and cultural contacts between the Hellenic world and the West.

During the same period, the dissemination of modern Western thought - one element of which was the glorification of ancient Greek culture - led to the gradual realignment of Greek culture along both classical and Western lines. All these developments, and the drivers behind them, involved not only a reversal of economic, cultural, and political isolation at least for some Greeks, but also created a broader movement that led to the emergence of a new national consciousness.

Exactly to what extent this national consciousness was new is a matter of scholarly debate, bearing in mind that “Greekness” had long encompassed - all the way since the Hellenization of the Eastern Roman Empire - all those speaking Greek and participating in Hellenistic culture.

Preparations for the uprising

In the 18th century, a number of secret organizations were founded with a view to preparing the uprising of the nation. Rigas Feraios (1757-1798) advocated for the formation of a Balkan democracy and outlined the plan for a Great Charter of Democracy, inspired by the French Constitution of 1793. The “Philike Hetaireia”, (Friends’ Society) - the most notable of the secret organizations - was founded in Odessa in 1814 with the aim of liberating Greece, encouraged by the revolutionary fervor gripping Europe in that period.

Those who embraced the initiative for the actual preparation of the uprising were primarily merchants and progressive intellectuals, who identified the ideal of liberalism with the ideal of national independence. Only in around 1819, when it became clear that the War was inevitable and imminent, did “Philike Hetaireia” appeal to members of the various governing groups, such as local chiefs, the clergy, and the Phanariots.

The misaligned and sometimes even conflicting orientations of the rebel groups made it difficult to define and consolidate a common course of action. Urban liberalism and rebellious spirits - especially among the intellectuals - found themselves at loggerheads with autocratic tendencies and entrenched interests, whereas a preference for immediate armed struggle clashed with a policy that wanted more time to prepare the populace, politically and culturally, as well as to secure the support of foreign Powers.

Support for the Greek cause

The Greek uprising also radiated the evocative power of classical Greek heritage during an especially receptive romantic era. As such, it was able to influence international public opinion and instigate a strong current of philhellenism that was probably underestimated by many governments at the time. Renowned and wealthy personalities, but also simple Western Europeans and Americans, joined the Greek revolutionaries.

The Greek Revolution and the independent Greek state were the end result of these manifold, diverse and often contradictory military, financial, social and ideological undercurrents, which in turn accelerated and shaped the course of the War.

The first constitutions

The inaugural activities for the formation of the modern Greek state reflect the ideological and political foundation upon which the revolted Greeks intended to construct their fledgling state: an amalgamation of elements inspired not only by the glorious ancient Greek past but also by the prevailing ideals of their contemporary times.

The first formal legislative texts were compiled during the course of the ongoing insurgency, which, tragically, included not only fighting against the enemy, but also episodes of civil conflict among the insurgents themselves. The three revolutionary Constitutions drafted in the National Assemblies of Epidaurus (1822), Astros (1823) and Troizina (1827) crystallized the political ideology of the War of Independence. These three Constitutions, modeled on democratic and liberal ideals, proclaimed that the Greeks revolted against foreign rule to establish an independent and democratic state, respecting human rights, for a nation whose glorious history was respected by the world.

These texts were a foundational moment in the modern political history of the country, as they awakened the consciousness of Greek society to the principle of constitutionalism. For the first time, ordinary Greeks were familiarized with the concept of representative government, the division of powers and the principle of popular sovereignty, as fundamental prerequisites for political stability.

The references, on the one hand, to the ideals of a democratic state, the Greek nation and its glorious ancestors, and, on the other hand, the very nature of the War marked by frequent in-fighting among competing Greek factions, are a stark testament to the tragedy but also the miracle that befell Greece after four centuries of foreign dominance.

European solidarity

Increasing civil conflicts as well as a string of military failures against the occupying forces in 1825-1827 had darkened the horizon, to the extent that by the summer of 1827, the course of the insurrection seemed doomed. This prospect was reversed by a number of international interventions.

The three major European powers, Russia, France and Great Britain, even though originally aligned to suppress revolutionary acts, were ultimately inclined - after the insurgency’s endurance - to intervene militarily in the naval battle of Navarino (1827).

Looking back on their heroic decade, Greeks could rightly boast that although liberation ultimately required European intervention, their bid for independence had been at their own initiative, without prior assurance or even likelihood of support from Europe, and that it was an initially successful insurgency that had forced Europe to come to their aid.

The Petersburg Protocol (1826), the London Convention (1827), the naval battle in Navarino (1827), the Russian-Turkish War (1827-1829) and the deployment of a French expeditionary corps in the Peloponnese (1828), were events of the utmost importance in consolidating the Greek independent state. After nine years of war, Greece was finally recognized as an independent state under the London Protocol of February 1830.

Heavy price for independence

Although the brave exploits of the Revolution forged a new image of “Greekness” and a new sense of national self-esteem, the War also cost the liberated provinces one third of the active population and two thirds of their fixed capital – an extremely heavy toll to pay. The duration of the War and the civil strife, as well as the long disruption of trade due to the separation of the liberated provinces from the rest of the Ottoman Empire, had a devastating economic effect which took at least two decades to repair.

The Revolution is celebrated by Greeks around the world as Independence Day on 25 March. Today, 200 years after the Greek Revolution of 1821, by re-examining and re-interpreting the historical events and finding the common thread between the past, the present and the future, we can piece together clear answers for how to consolidate progress, stability, solidarity, cooperation, development and freedom.

Revisiting - from all the different angles - the sacrifices of the armed revolutionaries and the people in 1821-1830 can help us appreciate the unity of purpose, determination, resilience, and solidarity needed to deal with new opportunities in a united Europe and with new regional and international challenges.

Every year, on the 25th of March, the Greek people honors the anniversary of their War of Independence, the re-emergence of their historic nation and the establishment of the modern Greek state. They celebrate the spirit of defiance against autocracy and tyranny, their opposition to oppression and their dedication to liberty, democracy and human rights.

By Ambassador Dionyssios Kalamvrezos