Cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin and Facebook’s digital currency Libra, may herald the future of payment systems, or even how we will exchange value over the Internet in the years to come. But for citizens across the planet and financial supervisors, these digital assets that have flourished over the past decade, are promising technologies but are, at best, difficult to grasp.

At worst, they have become synonymous with highly volatile assets that could put at risk the financial stability of the planet, and even the monetary sovereignty of nations, like many fear Libra could bring about.

The European Commission will unveil this autumn its long-awaited proposal on cryptocurrencies in order to seize the opportunities brought by these tokens powered by networks of computers: these include lower fees and almost instant transactions. Europe will become the first major jurisdiction to regulate these new means of payment.

“I believe that Europe is in a position to lead the way on regulation,” Commission executive vice-president for financial services, Valdis Dombrovskis, said in June.

In the EU executive’s thinking, new rules won’t scare developers and investors away, but rather the opposite.

The lack of legal certainty is often cited as the main barrier to developing a sound crypto-asset market in the EU, Dombrovskis recalled.

By becoming the first region to put its house in order, the EU expects to attract a market worth almost $350 billion spread over more than 6,700 digital currencies.

The Commission expects to achieve the holy grail of rule makers: to come up with legislation that will not only protect customers but will also spur innovation by designing a clear framework.

But before seeing what rules would be needed to rein in this fast evolving cutting-edge field, we need to take a deep dive into the past.

The ‘Tulipmania’

In February 1637, the Dutch were caught up in ‘tulipmania’. Tulip prices skyrocketed from December 1636 to February 1637, with some of the most prized bulbs seeing a 12-fold price jump. Tulips were not only exotic flowers but a speculative investment, with some wealthy individuals paying for bulbs what they would pay for a comfortable house.

The wild rush suddenly ended in February 1637, leaving some investors penniless in what is considered the first bubble-and-burst episode in investment history.

For some, the irrational fever that struck the Netherlands is a cautionary tale for the hype surrounding cryptocurrencies, as the story of Bitcoin reveals.

The obscure payment method became a primary target for speculators. The price of one Bitcoin skyrocketed almost 10-fold in the second half of 2017, reaching nearly 20,000 dollars (16,960 euro) at the end of that year. In December 2018, one Bitcoin was worth around 3,300 dollars (2,800 euro), around 75% less compared with the all-time high.

Since then, Bitcoin prices recovered some of the lost ground (price as of early September is just below €9,000), but doubts around crypto-assets persist.

Created in 2009 after the housing market crash by the mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto (a pseudonym), Bitcoin brought lower fees for online payments and a decentralised authority, aligned with the libertarian spirit firing the digital world.

Bitcoin balances are kept on a public ledger, supported by a network of computers that everyone on the network can see. This is the blockchain technology that powers every cryptocurrency.

For some, blockchain is the greatest technological breakthrough since the Internet. Author and consultant Don Tapscott told top EU analysts back in 2015 about its potential, when the technology was still nascent. While the first generation of the Internet enabled us to communicate information only, the second generation, based on blockchain technology, allows users to communicate value and money in a peer-to-peer way, he said.

Bitcoin’s rollercoaster ride in the markets eclipsed the potential of blockchain. But regulators across the world are not only concerned about the volatility of these digital tokens and the impact that the Bitcoin frenzy could have on users. They are also wary of some of its beneficiaries, as the anonymity provided by Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies made them an optimal payment method for drug dealers and other illegal activities.

The slow progress of authorities in Europe and elsewhere to regulate it and the struggle to fully understand and legislate without killing it, significantly changed in the summer 2019.

Libra’s earthquake

That June, Facebook announced that it would launch in 2020 a ‘stablecoin’, a digital currency backed by the “best performing independent currencies”, to offer cheap and fast means of payment to users.

The announcement provoked an immediate backlash from governments and central bankers. Users were also uneasy with the social network’s intentions to build an alternative global system for instant payments, in light of its poor record respecting their private data.

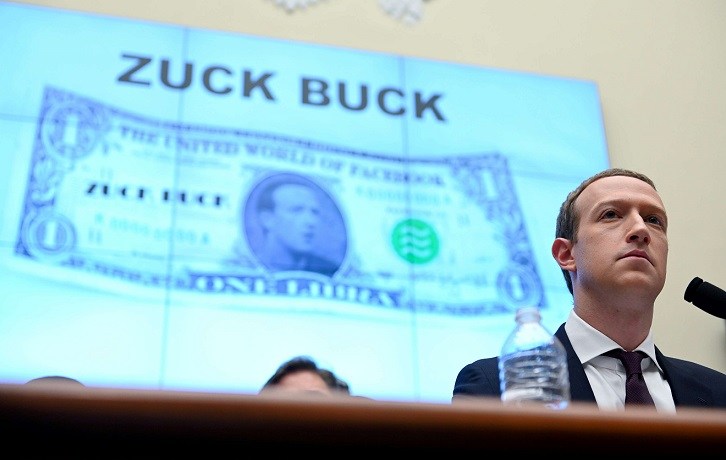

Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg testifies before the US House Committee on Financial Services in Washington, October, 2019. National authorities fear that their cryptocurrency project, “Libra” could destabilise the global economy, given the substantial reach by the social media giant.

The irruption of the social network pushed cryptocurrencies to the top of the priority lists for regulators across the world, concerned not only about their price instability and dodgy users, but also the implications for the global economy as a whole.

The reason is that Libra is a “stablecoin”, a type of cryptocurrency backed by a reserve asset, in this case a basket of sovereign currencies.

By being tied to national currencies, Libra wants to address the high volatility of cryptocurrencies. But national authorities fear that it could destabilise the global economy, especially when you can reach potentially 2.7 billion users around the world.

“We will not accept that Libra is transformed into a sovereign currency that can endanger financial stability,” French finance minister, Bruno Le Maire, told us in an interview in July 2019, on the eve of the G7 finance ministers meeting, where France sent a strong warning to Facebook.

Dante Disparte, deputy chair of the Libra project, said in December last year that “we have always said that the project would seek to be regulated.”

But he asked for the “same risks, same rules” principle that regulators defend in Europe.

“Don’t push Fintech innovations of any size offshore from the European market because, in the long run, it is going to be bad for the economic competitiveness of the region,” he stressed.

The concerns erupted across the world, and the withdrawal of some initial partners from the Libra project, including Visa and Mastercard, led the Libra Association this spring to lower its ambitions, by offering primarily stablecoins backed by only one sovereign currency, becoming in practice digital versions of national money.

By scaling down their plans, Facebook intends to convince financial supervisors of their reasonableness in order to win their approval when it is finally launched in the EU. But it won’t be easy.

While US authorities apply existing rules on cryptocurrencies, the Commission drafted new legislation (announced for autumn 2020) to rein in these digital assets.

The rules will come after more than two years of slow but steady progress to regulate cryptocurrencies, a Commission official told The Brussels Times magazine. “Libra was a ‘wake-up call’ to take seriously these developments.”

The EU executive was wary from the outset of the risks of over-regulating because of Libra, as Europe could strangle the innovation brought by smaller Fintech firms.

As a result, the Commission designed a set of rules that will be proportionate to the level of risks. Less risky cryptocurrencies will face lighter legislation, while for global cryptocurrencies such as Libra, rules would be stronger, given that they are likely to raise challenges in terms of financial stability and monetary policy, warned Dombrovskis before the summer break.

The new European framework will substitute the national rules that are starting to emerge in a few member states, including France, Germany and Malta. Once the cryptocurrencies win regulatory approval at EU level (by following a series of requirements, depending on their risks), they would obtain a EU-wide ‘passport’ to operate in the bloc.

Our central bank’s account

Libra also became a ‘wake-up’ call for central bankers. A recent survey among 66 central banks by the Bank for International Settlements showed that more than 80% are working on central bank digital currencies, including the ECB.

Yves Mersch, member of the executive board of the ECB said last May that Frankfurt wants to be ready “to embrace financial technological innovation, which has the potential to transform payments and money faster”.

Although most of the money issued by central banks is in fact already digital, it is accessible only for banks. Their new digital currencies could make their balance sheets accessible to citizens, a true game-changer. In other words, we could have a deposit account in our central bank.

This scenario would have major consequences for the banking industry, as savers would prefer to have their money in the safe hands of the ECB or the Federal Reserve, given the long history of banking crises.

For that reason, central bankers are thinking twice about how to design their digital currencies without provoking a financial earthquake.

The journey won’t be either short or easy, as every step forward in the crypto-world has brought new challenges. While ‘stablecoins’ addressed the volatility of Bitcoin and the first cryptocurrencies, Libra still does not meet the standards of commercial bank money.

Meanwhile, central bank solutions still raise “profound questions about the shape of the financial system and the implications for monetary and financial stability”, and their own role in the system, Andrew Bailey, the governor of the Bank of England, said on 3 September.

Like every new technology, cryptocurrencies must overcome numerous obstacles and address many outstanding risks. But the sense of direction is clear. The future of money is already here.

By Jorge Valero