Princess Delphine of Belgium pauses as she searches for the right words to describe her struggle for royal recognition. “Princes and kings never impressed me,” she says. “I never, ever dreamed of becoming a princess. But I knew that if I didn’t do something, I was always going to be known as the bastard.”

Delphine is describing an ordeal that lasted the better part of two decades: her fight to be legally recognised as the daughter of King Albert II. It was gruelling. Albert refused to admit that the ‘secret princess’ was the result of his 18-year, extramarital affair with her mother. It was only in January 2020, after a court-ordered DNA test proved he was her biological father, that the former king acknowledged Delphine as his love child. A few months later, she was formally accorded the right to the title of princess and a royal surname: Delphine Boël became Delphine of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

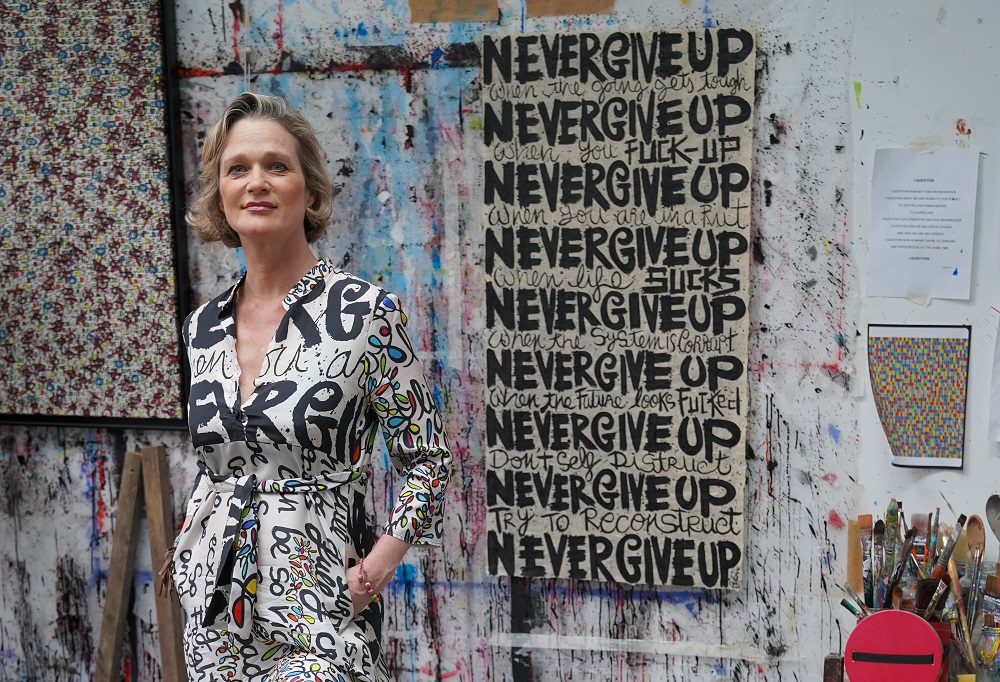

But right now, she just wants to be known as Delphine, the artist. She is showing me around her paint-flecked studio in Uccle where she creates her vibrant canvasses and sculptures. The 54-year-old, who studied at Chelsea College of Arts in London, is preparing for a new show in Saint-Tropez. It is rare for a royal in any country to have a job, but Delphine was never going to drop her work simply because she had a title.

“Some people might think, ‘Well, you’re a princess now you, you are paid by us,’” she says. “But I’m not. I work. And I’m a mother too. I am not paid by the government. So I'm not part of the ‘dotation’, which is something I would have not liked. I'm a full-time artist. That’s how I live. And that's how I will live.”

Delphine in her studio

While rejecting the idea of a state handout, Delphine is fully aware that her extraordinary experiences have transformed her situation. Her campaign for recognition was a gripping saga – and not just for Belgians, as she now has an international profile.

It was not what she wanted. From an early age, Delphine knew who her biological father was. Albert, who she nicknamed ‘papillon’, or butterfly, was a constant presence in her childhood, even taking her on holiday. Her mother, Baroness Sybille de Selys Longchamps, was married to industrialist

Jacques Boël. Albert was seen as a playboy prince but was married to Paola, a glamorous Italian aristocrat. Albert’s elder brother, Baudouin, was king at the time of the affair.“My mother thought she couldn't have children,” Delphine says. “She had nine miscarriages with Jacques. And then she started seeing Albert. She was separated from Jacques but still officially married to him.” Boël did not raise Delphine but instead was used as a cover to protect the royal family. The outside world did not know the truth, even after Albert was crowned king in 1993.

Hiding from paparazzi

The story only became publicly known in 1999 after an enthusiastic teenage writer published a biography of Queen Paola, which included a throwaway line about Delphine. “It was a bit strange,” Delphine says. “A lot of people discovered through one line, in a book about Queen Paola, my father's wife. And then it all went bonkers.”

At the time, Delphine was in London, where she had spent most of her life. “I suddenly found myself a bit like in the movie Notting Hill, with paparazzi all over. They started in France at my mother's place. I went to London thinking, naively, that nobody would be there. And this went on for weeks, for months.”

She remained in contact with Albert throughout. “He kept saying, ‘Don't worry, it's not going to carry on forever. Just stay calm and live your life.’ So I left it like that. I still felt very protected by him. At one point, the palace suggested that I should disappear to anywhere far, like Zanzibar or wherever but I didn’t want to leave London.”

The scandal seemed to blow over. But then in 2001, after Delphine’s mother fell ill, Albert froze her out. “I was very worried about her,” she says. “And I felt very alone. You know, I had no brothers and sisters, and I was like, ‘Oh, God, you know, what if she dies.’ So I give him a call. And that was…a very hard phone call. He said abruptly that he wasn't my father.”

The change in tone stunned her. She tried to explain it away, thinking it might have been down to a backache, one of his ailments at the time. “I never will know for sure why he did it,” she says. “I think the people surrounding him at the time had some influences. But he had known me until I was 33. I wasn't a bad person. But people started saying that I was a troublemaker.”

She initially kept the incident to herself, but eventually told her husband, Jim O’Hare. “It was so painful,” she says. “I had to tell somebody because I couldn’t keep this to myself, which I'm glad I did. Because if I hadn't, I would have thought, ‘Did I dream it?’ Which we do, as human beings: we kind of wonder if some things are true, if they really happened, which is a way of protection for our wellbeing.”

Art as a voice

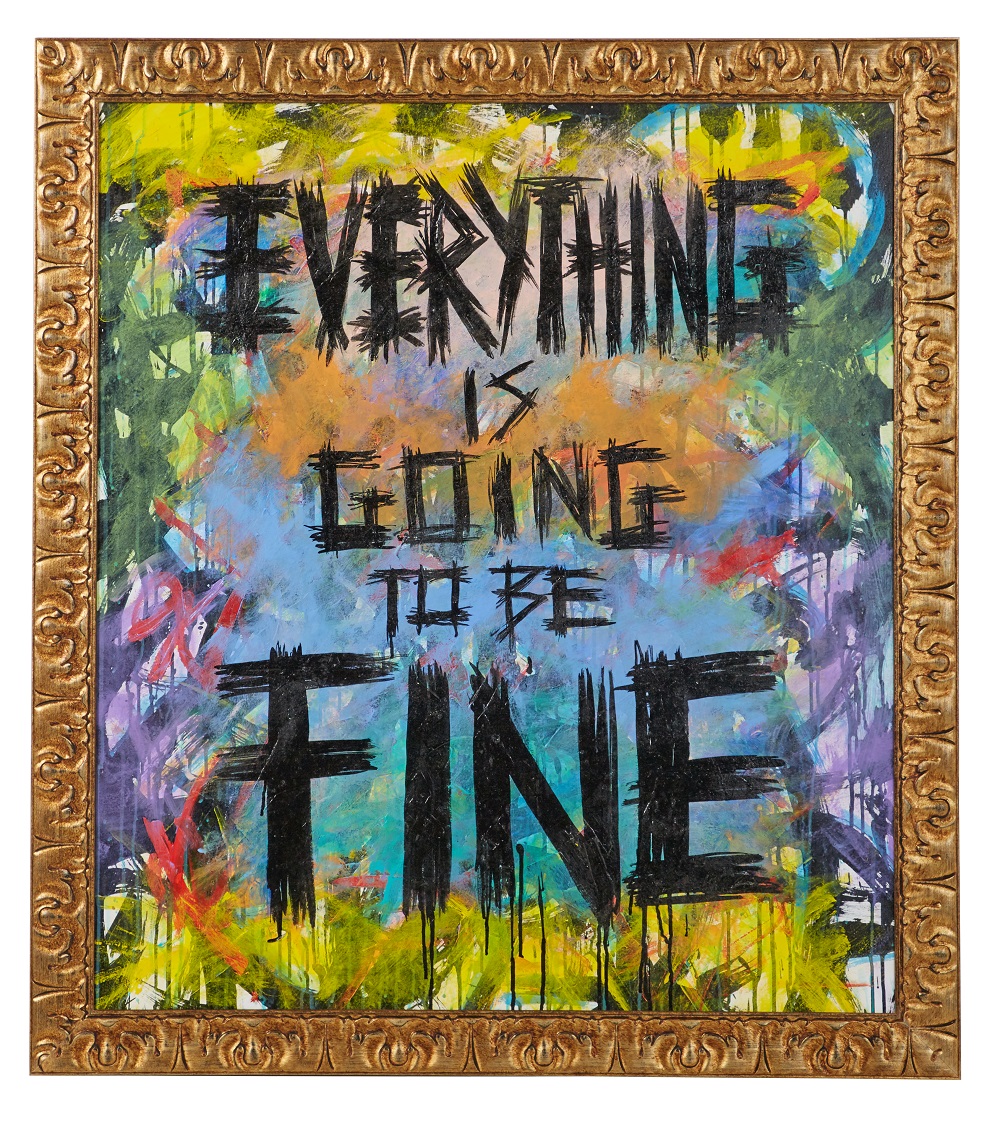

At that point, Delphine paused her art shows, fearing the furore would undermine efforts to exhibit her work on its own merits. After the break with Albert, she decided to pick up her brushes again. “I thought, ‘If I am asked, I'm going to exhibit, and people can read what they want to read into it,’” she says. “My art became my voice. It wasn't obvious to everybody, but it helped me to cope with the situation. I did lots of work with humour. I surrounded myself with colour, with funny-looking objects, so the whole situation become more fun and less hard – and that really saved me.”

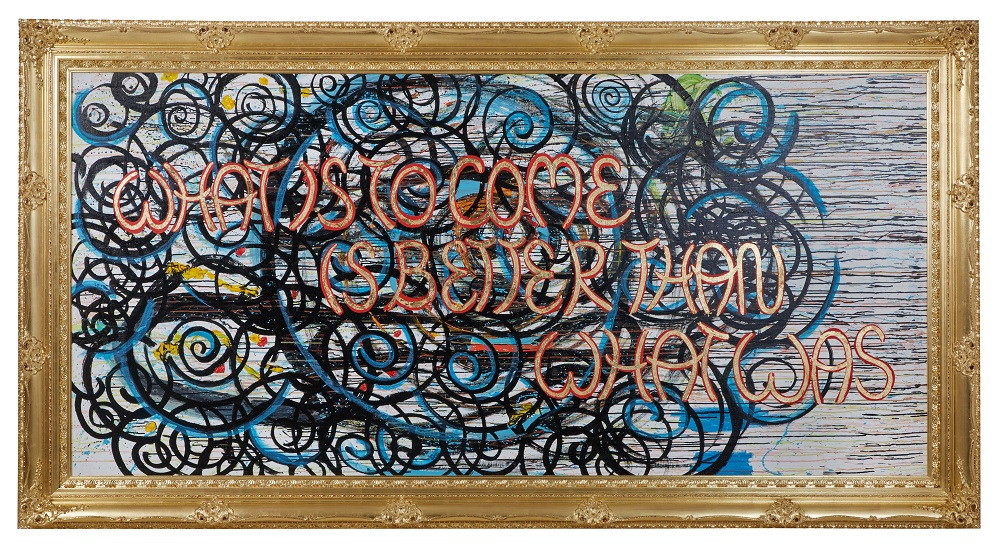

What is to come is better than what was

The colours jump out. The effect is multiplied by the mirrors and shiny surfaces she uses. Words are scrawled boldly across her paintings, scratched into the mirrors and even printed on the clothes she designs. Her most reoccurring motif is ‘love’, which has been moulded into a five-metre-high steel sculpture, entitled 'Ageless Love', on display in Sint-Niklaas’s Gerdapark since the end of 2020. She also pokes fun at herself in her art: one piece in her studio simply features the words ‘love’ and ‘child’ with a neon heart between them.

Parenting emotions

That lightness and joy, however, was still some distance away two decades ago when she tried to return to her art. Delphine was an object of curiosity in Belgium, where the press and public would speculate on whether she was Albert’s daughter. “This went on for years, and I always stayed quiet,” she says. “And then I had children. I had my daughter in 2003. And that's when a lot of emotions came out.”

The process of becoming a parent made her revisit her own experience. Her first child, Joséphine, was born in 2003, followed by Oscar in 2008. “When you have a baby, you obviously think more about what it means to be a mother or father. And I realised that this baby didn't ask to come here. I'm responsible and Jim is responsible,” she says.

More pertinently, Delphine began to question Albert’s behaviour towards her. “I started to think, ‘This is not normal.’ I also wondered whether this would carry on, and what would happen to my children. What's going to happen to them when they're older? Are they always going to question who their mother’s father was?”

At the same time, her art career was impacted. Galleries would turn her down, saying her name risked becoming a distraction. “This happened many times,” she says. “And it didn't come from the palace. It came from people worried about annoying the palace because of me. And I thought to myself, ‘My God, is it stalking my work?’ It was attacking my livelihood.”

Stormy Day

She and O’Hare would also find themselves uninvited to events where members of the royal family were expected. “It made a lot of people paranoid about us,” she says. “Which was silly. Because it wasn't the palace saying anything. But by not saying anything, that's what he'd created, right? If you, as a powerful figure, don't say, ‘Stop it, be cool, it doesn't matter if we meet each other,’ then it has the same effect.”

Delphine recognises that this is all a long preamble to explaining her situation, but she says it is important to show how her eventual legal action, launched in 2012, was not an overnight whim, or a grubby scheme to extort money and fame from the palace. “We didn’t want to go court at first,” she says. “I was terrified of the courts – especially living in Belgium, where my children would face this. But then it came to a moment where it was not possible to avoid it anymore. I realised we would have to go down that path, and just let the law decide.”

The legal battle dragged on for years. “It was really unpleasant for all of us, me, my children, and my father, of course, and everybody. Extremely unpleasant,” she says.

Albert continued to deny his paternity, but when he abdicated from the Belgian throne in 2013 in favour of his son, Philippe, he lost his legal immunity. In 2019, a court eventually ordered him to provide a DNA sample or face a fine of €5,000 for every day that he refused.

After the test came back positive, Albert grudgingly admitted he was Delphine’s father. A later court ruling granted her the same rights and titles as her father's legitimate children – while Joséphine and Oscar were recognised as Princess and Prince with the style of their Royal Highness. “Sometimes in life, you have to go through the muck,” she says, with a sigh. “Sometimes, there will be horrible moments. But you need to get through them.”

Breaking taboos

She also takes pride in breaking taboos about children born out of wedlock, who now outnumber those from married couples in Belgium. “Or if you have a bastard child, or if you have children from a first marriage that you don't want to hear anything about anymore,” she adds. “All children should be treated equally. Whatever the reason you’re not together, it shouldn’t be the child's problem.”

Delphine says she was spurred on during the court battles by the thought that she might be helping children who had to hide their parentage. “I knew that by me doing this, I would be an example. And the law was so medieval, towards people who want to know who they are, their identity, or why they have been treated differently because of adults, changing families and so on,” she says.

Until recently, fathers who did not want to recognise a child could take advantage of a law that said that their parental responsibility was rendered null if the child did not make a formal move before they were 21. Or as Delphine puts it: “If you don't say something, zip it. You'll never get a chance again because you're too old.”

The effect of her campaign for recognition has been to shine a light on the issue. But it has not, she says, led to the courts being flooded with new claims. “Just the opposite,” she says. “It's actually given an outlet for private discussion. It's levelled the playing field in favour of the child.”

Reconciliation

But for all the pain of her break with Albert, and the long legal battles, Delphine jumped at the offer of reconciliation. At the end of 2020, King Philippe made the first move, inviting Delphine to join him for lunch at the palace. “That first meeting was wonderful. We got along very naturally.”

Then, a few days later, Albert and Paola invited her to the Belvédère Castle, the royal couple’s official residence just outside Brussels. Was this awkward? “No, it wasn’t at all,” she says. “It's as if we had never parted, which is very, very strange.”

That led to meetings with the rest of the family. Again, Delphine says it was not nearly as tricky as one might imagine. “When you are really related, something happens and it's natural. I can't explain it. When it's really your blood,” she says. “The whole family is trying. We don't see each other every five minutes. I’m busy, they’re busy. Some people think that we sit around all the time and drink tea. It's not like that. But little by little, we are getting to know one another.”

Delphine is keen to dispel any ideas that becoming a princess is a Disneyesque fairy-tale with tiaras, ballgowns and golden coaches. In Belgium, it is more about banal bureaucracy, even for a newly-minted royal. “The was lots of paperwork to change,” she says with a sigh. “The title is integral to your name. And it’s only legal in Belgium when you change your name. So my passport changed and my children's passports changed.”

And because she is Belgian, she is known by three different names: the French Delphine de Saxe-Cobourg, the Dutch Delphine van Saksen-Coburg, and the German Delphine von Sachsen-Coburg. However, her children kept Jim’s family name, O’Hare, with the addition of the prefix HRH, followed by the title Prince and Princess of Belgium. The prefix and title are the same as those for Albert’s other grandchildren.

Good causes

Now that she is in the public eye, Delphine says she wants to use her profile to promote good causes. “I'm not particularly religious, but I do believe that one is in the world for a reason. And we all have a mission,” she says. “I feel very strongly about supporting people who are treated differently because of their background, colour, sexuality, or whatever. I feel very close to that and hate people being bullied simply because they are not like everybody else.”

Her charity work includes supporting breast cancer research and awareness, and “anything to do with children, and physical and mental illness.” She is also associated with the Make-A-Wish Foundation, the US-based group that helps children with critical illnesses and operates in Belgium. It was her chosen charity last year when she took part in a celebrity edition of Belgium’s Dancing with the Stars TV show – appearing in a tight, black PVC outfit, referencing the movie The Matrix. “Sometimes, you have to do things that are a little bit out there,” she says.

But there is a limit to what she is ready to get involved with. “I'm not going to just do anything,” she says. “I'm asked to do a lot of reality programmes, like going on a remote island and other weird stuff. No, that's not my thing. OK, there was the dancing, but it’s still a very artistic language for me.”

Delphine also wants to use her profile to champion young Belgian designers who express “extreme Belgitude”. At the Belgian National Day parade on July 21st, she wore a bespoke red outfit with inlaid bird images created by Pol Vogels, a 25-year-old designer from Heusden-Zolder in West Flanders. The dove, symbolising peace and hope, reflected the times, she says, as Belgium and Europe deal with the war in Ukraine and the challenges of the post-pandemic recovery .

As she adapts to her new royal role, Delphine wants to weave art into her public activities. “I use art in my royal moments. My art and my life is the same for me. I don't cut the two,” she says. “At the parade, my brothers and sister wore military uniforms with medals and sabres to show they're doing good things in defence of the nation. By choosing artists, by promoting Belgian art, I’m also doing something for the country.”

Day job

Delphine is adamant that she wants to continue her day job as an artist. “I'm very happy that I have had a whole career behind me. That was also very important for me to prove myself before anything like this could ever happen,” she says.

Her show in Saint-Tropez at the Linda and Guy Pieters Foundation is called ‘What Is To Come is Better Than What Was’. It features massive paintings with slogans such as ‘Everything is going to be fine’, wrapped in heavy gold picture frames. The message is therapeutic: indeed, she hails art as a shield and tool of survival. “When I was going through these difficult years, I kept myself going with all these phrases, like a mantra to help me through this stuff,” she says.

Still, she insists her royal status will not affect her too much. “I've always been Delphine and I'm still Delphine. And like most artists, I put my soul up on the canvas,” she says.

Nor has it raised her marketability. “I don't sell more now,” she says. “I'm exactly the same. I had already done a lot of shows, and I was known as an artist. People are not stupid: they invest in the work they believe in. And I'm doing very well. But I was doing very well in my heart. And in some ways, it's more difficult, because many people find it hard to believe that a princess is doing art…is it really art? You have to fight harder for your place. Well, I’m trying, at least.”

She is also working in different mediums: as well as canvases, mirrors, sculptures and clothes, she recently designed the colours for a Lamborghini Huracan for 20-year-old Brussels-born racing driver Esteban Muth, currently competing in the T3 Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters. The artwork features one of Delphine’s poems called 'Never give up’, a text she has also printed on her dress (which includes a deliberate spelling error: self-distruct instead of self-destruct).

And Delphine is already looking at other ideas. Her Saint-Tropez artworks have already been shipped out of her studio, but on the floor are two pairs of trainers that she has dribbled paint on, in a Jackson Pollock manner, but more elegant.

Delphine has been running since she was 11, and always keeps her old trainers. When they are too worn to run in anymore, she uses them for her work. “I've got this whole stack of shoes, so I might as well do something with them. I didn't paint the inside because you can see they're really worn. And when you look at them, at how the paint sort of ripples off, I think they're fun. They've been with me for so many years. I just love them,” she says. “And they've got a story.”

Just like Delphine herself.