More than half of the Brussels-Capital Region's surface consists of roads, buildings, squares and other concrete infrastructure which prevents water from infiltrating into the soil. The consequences can be alarming, particularly in periods of heavy rain.

The torrential rain that flooded Spanish cities in October raised concerns among European urban residents about how well-protected they would be in the face of flash flooding. Surface permeability – or to what extent the ground is covered by materials that would prevent the absorption of rainwater – is one way to measure this risk. Based on this, Brussels is very vulnerable to situations such as the one witnessed in Valencia.

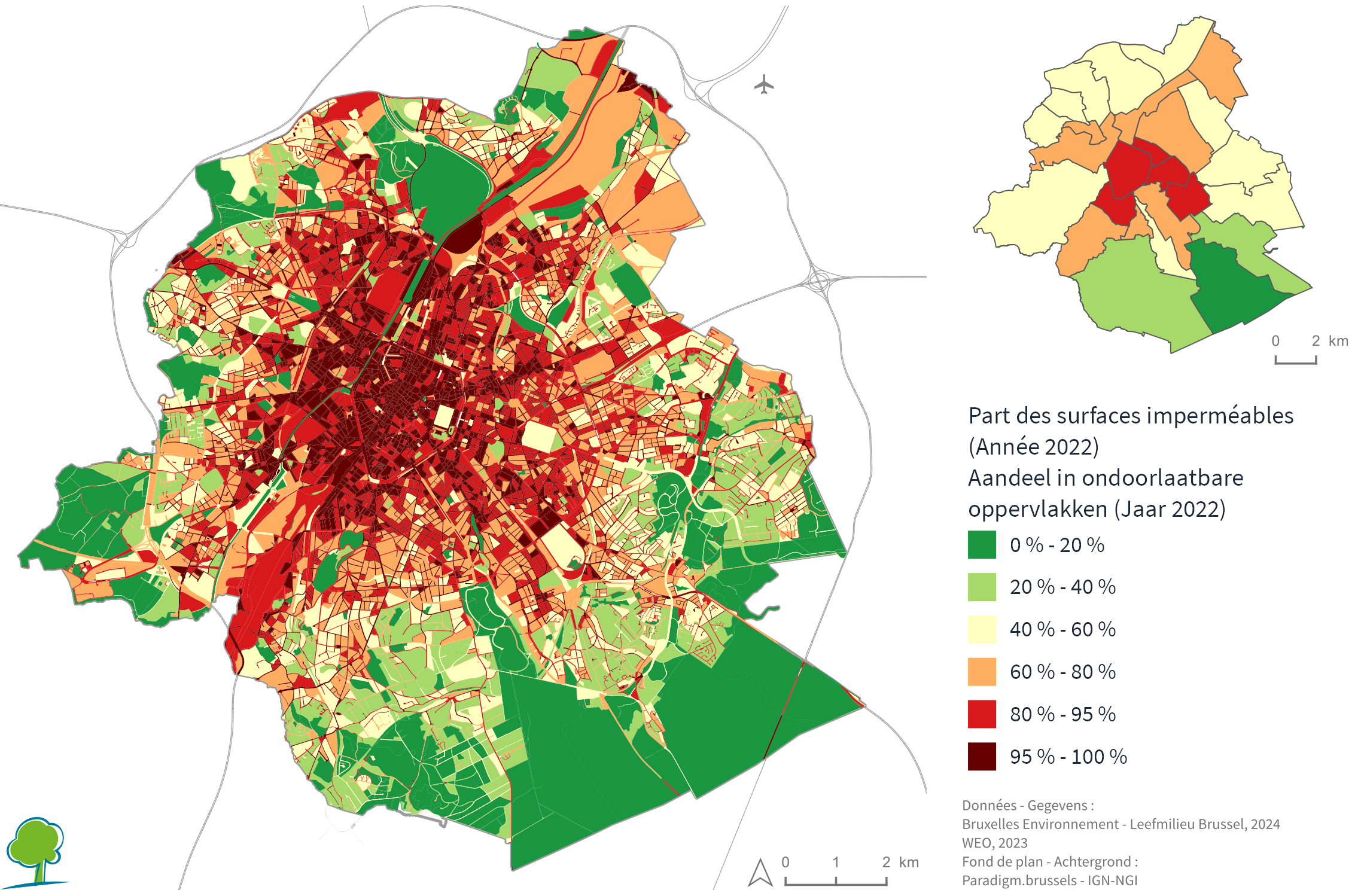

Using artificial intelligence based on satellite images and aerial photos, regional agency Brussels Environment has shown that over half of the Brussels region (53%) is impermeable, meaning water cannot infiltrate. If the Sonian Forest – the region's largest green space – is excluded from the equation, this figure rises to 60%.

This means that if Brussels is faced with heavy precipitation, the surface runoff will be exacerbated because of the concrete, and the flooding will be much more intense.

Brussels downtown, heart of stone

The percentage of surfaces in the region where water cannot infiltrate the soil has doubled since 1955 and increased linearly since 1993, Brussels Environment found.

The situation is particularly concerning in the centre of the region, referred to commonly as the Pentagon due to the shape of the area, located inside the Small Ring Road. Here, 93% of the surface does not absorb rainwater, with most neighbourhoods consisting of high building density, surrounded by roads.

The share of Brussels' surface that is impermeable. Credit: Brussels Environment

"Only the region's large green spaces, such as the Sonian Forest, Bois de la Cambre and Woluwe Park, as well as other large vegetated spaces, such as the Brussels cemetery, stand out as permeable surfaces," the agency said.

This high level of paving is not only concerning when it comes to protection against heavy rain. It also poses problems for refilling groundwater reserves, three-quarters of which is used for drinking water for the Brussels population, meaning supply could be in peril. The remaining 25% of extracted groundwater goes to the industry sector and other services such as swimming pools and carwashes.

Finally, the concrete nature of Brussels also threatens the urban microclimate, which also regulates the so-called "heat island effect". (This refers to the fact that periods of warmth are much more acute in Brussels than in surrounding rural areas.)

In Brussels, temperatures are, on average, up to 8°C higher than in surrounding rural areas, and the number of heatwave days in the region is expected to further increase. This poses serious threats to public health, infrastructure and resources.

'Inspiring action'

Brussels Environment said its surface permeability map can be used as a tool to manage water resources and mitigate the effects of flooding and heat islands. It also aims to raise awareness and inspire action.

"Reducing impermeable surfaces and promoting natural infiltration to reduce flooding and other negative environmental impacts is of great importance," the regional body said. It advocates the creation of more green zones, permeable paving, green roofs and rainwater harvesting systems.

Brussels Environment also pointed to the importance of its Good Soil strategy. Among other things, this examines the feasibility of discontinuing soil paving in Brussels by 2050 and softening certain soils that are already sealed. The aim is to restore the water cycle and prevent flooding.

Finally, soil softening has become a priority for regional authorities when issuing environmental permits. Many projects include measures to ensure a certain percentage of planting to make soil permeable.