What is the greatest film of all time? We all have our favourites, but the ranking that cinephiles take seriously is the once-in-a-decade poll by movie magazine, Sight and Sound, and in December 2022, there was a new winner: Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles.

Directed by Belgium’s Chantal Akerman – the title is somewhat of a giveaway to her origin – the film emerged as the favourite of some 1,600 critics, academics, curators and archivists, overtaking previous champions, Vertigo and Citizen Kane.

The result was a shock. Not only because it was the first time a film made by a female director came out on top of the list, but also because most people outside of die-hard cinema circles had never even heard of this film. Even in Belgium, in whose capital the film takes place, most news outlets reported jubilantly about this Belgian victory, while in the same breath declaring the film “completely unknown”.

This is a shame. Akerman is recognised abroad as one of the most influential filmmakers of her generation, hailed by the likes of Todd Haynes, Michael Haneke, Jia Zhangke, Gus Van Sant, Joanna Hogg and Marguerite Duras (herself part of the French New Wave that inspired the young Akerman to start making movies in the first place).

Why did they look up to her? It was not just that she pioneered slow cinema, using techniques that had never been seen before. They also saw Jeanne Dielman as revolutionary in its subject matter: someone was turning the camera on the ordinary life of a housewife, insisting that she deserved our attention. Until then this had barely been the case, and certainly not for an entire movie and with such a keen eye for the details. Akerman mastered the method, focusing head-on with Dielman, using long takes and scrupulous framing. She brought viewers into the kitchens and living rooms, where dramas akin to those in the outside world took place, but on a much more intimate scale.

Akerman also put the female experience at the centre of her films, without turning her female protagonists into symbols or victims of their womanhood. The friction between what is on show and what we are not supposed to see is both a driving force and an ingenuity, making Akerman as much an innovator and iconoclast as anyone in the French New Wave or the American avant-garde.

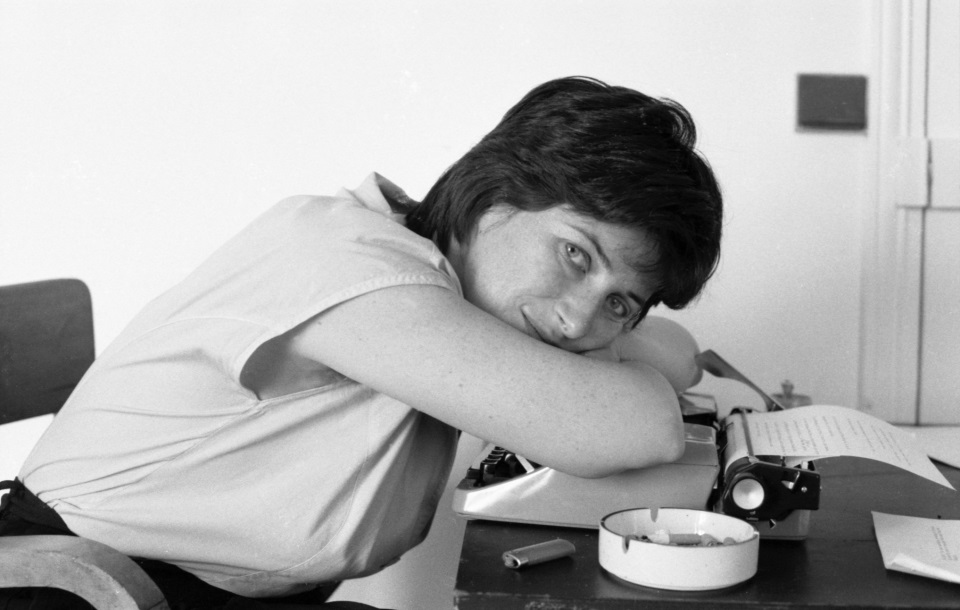

Chantal Akerman

Akerman’s lack of recognition in her home country also overlooks how her films, settings and writings have prominently featured Brussels as their location and subject. Her works lend themselves to many different readings, but they usually feature a long and multifaceted love letter to the city where she was born.

Who was Chantal Akerman? Born in the Brussels commune of Etterbeek on June 6, 1950, she was the oldest of two daughters of Jewish Holocaust survivors from Poland. Her mother, Natalia, was deported to Auschwitz with her parents; only Natalia would return. The war and its aftermath loomed heavily over her childhood, even though her mother refused to speak about her experiences. It would also permeate Akerman’s films.

Wandering and Warhol

Akerman was extremely close to her mother, even if she would later describe her childhood as suffocating. But she was smitten by film from an early age: after seeing Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot Le Fou, at age 15, she knew that her life would be in cinema. After a short spell at the Belgian film school, Institut National Supérieur des Arts du Spectacle et des Techniques de Diffusion (INSAS), she briefly moved to Paris, and then ended up in New York. This rounded out the triad of cities where she would alternatively attempt but “fail to make a home for myself.”

In New York, she found work as a cashier for a gay porn theatre, delving into the avant-garde art scene where she met the artists that would become key influences: artist Andy Warhol, filmmakers Jonas Mekas and Michael Snow and choreographer Trisha Brown. She would finance the short films she made at that time by stealing money from the porn theatre. On her return to Belgium, Akerman made her first feature film, I, You, Him, Her (Je, Tu, Il, Elle). Released in 1974, it presented a groundbreaking vision of queer cinema, not least because of its graphic and desperately romantic, ten-minute love scene in which the director herself partook.

A year later, in 1975, Akerman would direct Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, the film that made her name. She was just 25 at the time. Over almost three-and-a-half hours, it recounts three days in the life of the titular widowed housewife, while she does nothing more than cooking, cleaning and taking care of her household and son. Except when she prostitutes herself to make ends meet. In long, uninterrupted shots we see the painstaking routine of a woman who tries to stave off an imminent danger only she seems to be aware of. It is only in the final hour of the film that her routine unravels.

Akerman would explore many other film genres and approaches, careful not to repeat herself. Musical comedies, documentaries shot around the world, an adaptation of an early Joseph Conrad novel and even a screwball comedy about psychoanalysis with Juliette Binoche and William Hurt. Her filmography is as diverse as it is prolific. In the 1990s, she began to deconstruct her films into installations for galleries and museums. She also wrote four books: a play, an autobiography through film of sorts and two memoirs.

Akerman never escaped Jeanne Dielman because she could not escape the woman she partially based her on, her mother. For her final film project, Akerman turned the camera for the first time directly on Natalia: in No Home Movie (2015) we witness the last days of a mother in physical decline and the daughter who takes care of her in the family apartment in Brussels. The silence that defined their relationship is kept intact until the very end. No Home Movie was released just after the death of its leading lady. However, its director would not survive much longer either. Chantal Ackerman died on October 5, 2015.

The city and the cineaste

For all her worldly wanderings, Akerman would return to Brussels again and again. Three of her works bear its name in their titles: Jeanne Dielman of course, but also a film she made for French television in 1994 called Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the 60s in Brussels (Portrait d'une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles) and the 1998 memoir, A Family in Brussels (Une famille à Bruxelles) about her father’s demise.

Jeanne Dielman is mostly filmed inside the apartment, but there are glimpses of the city when we follow her doing errands. In between stores, she drinks a coffee in a bar at the Place Alphonse Lemmens in Anderlecht. And during her quest for a button for her son’s coat, she walks under the tram wires of Place Barra in Saint Gilles and later, away from the Halles Saint-Géry. Ironically, the most exalted address in Belgian cinema has the wrong postcode: while the Rue de Commerce lies just outside the Brussels city pentagon, it is still within the 1000 zone.

Scene in Brussels from Jeanne Dielman

However, to see Brussels portrayed in its full splendour by Akerman, look elsewhere. Michelle, the young girl in Akerman’s Portrait, spends a whole day on the streets of Brussels while skipping class. We meet her first at the Brussels-South train station, and later, she goes to a movie screening at the Cinematek, the Royal Belgian Film Archives on the Mont des Arts. That is no coincidence: Akerman said that after dropping out of film school, she received her film education by watching old movies there. Even the drinks Michelle has with her friends take place in the bars in its vicinity. After the movie, Michelle has her first kiss from a boy in the nearby Central Station.

While three of her films have the city’s name in the time, there was another that Akerman made which, in her own words, “is about Brussels”. All Night Long (Toute Une Nuit), made in 1982, takes place over a single hot summer night, meeting almost a hundred lost souls in the bars and restaurants, hotels and apartments in the centre of Brussels and its suburbs. A chain dance of love and loneliness, it is also a period piece about Brussels before its gentrification and an ode to its haphazard city plan. The Place de la Vieille Halle aux Blès is the key venue, in particular, the building where three amorous couples still watch over the vicissitudes in the square below (Akerman would doubtless be amused to see that the square now has a permanent resident: a statue of Jacques Brel).

Station to station

However, the most beautiful sequence about Brussels in any Akerman movie is the arrival of Anna by train in The Meetings of Anna (Les rendez-vous d’Anna), made in 1978. Played by Akerman’s frequent collaborator Aurore Clément, Anna Silver – who shares many biographical details with her creator — makes a stopover in Brussels for a single night on her way from Cologne to Paris, but Akerman makes that night worthwhile.

Approaching the city by train, the camera slowly glides into the Brussels-North station, diving beneath the city towards the Central Station and then pausing between the illuminated canopies of the Brussels-South platforms.

In symmetrical shots, Anna takes the escalator down into the station’s concourse where she embraces her mother who has been eagerly awaiting her. No other scene in her work better encapsulates the relationship Akerman had with the city she could never escape, however hard she tried.