It looked at first like a typical Flemish suburban villa. Trimmed hedge. Car parked in the drive. Caravan ready for the summer getaway. But there was something odd about the house on Bernard De Vadderlaan. It was built entirely of wood in a half-timbered style. All the other houses on this suburban Antwerp street were sturdy brick or stone constructions. The fragile timber house at number 23 didn’t seem to belong in this quiet neighbourhood.

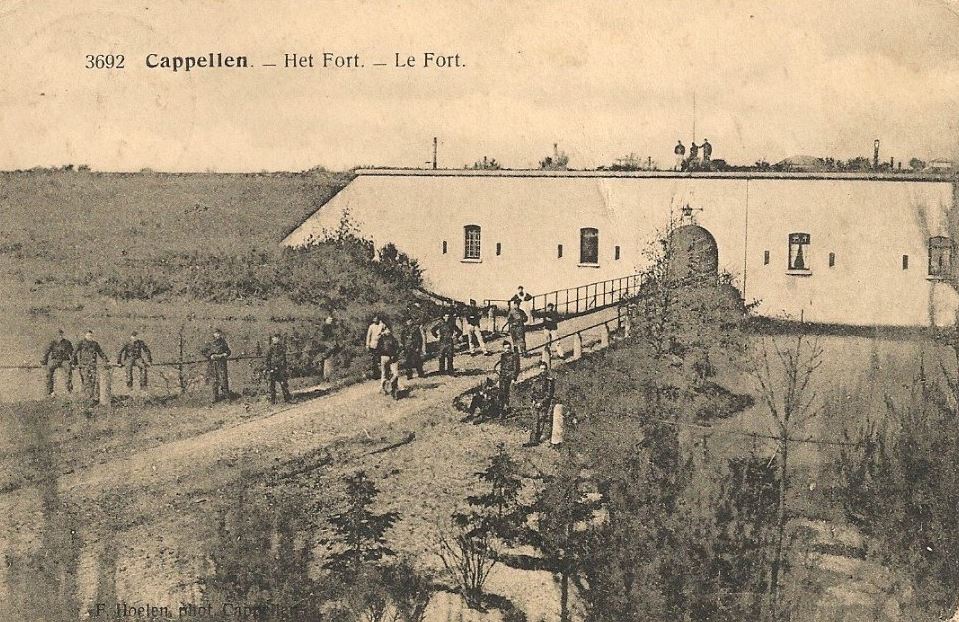

The explanation lies a few hundred metres away. The street leads to an area of dense woodland. Hidden in the trees, the massive Fort van Kapellen was begun in 1908 to defend Antwerp. It was one of 34 forts built over several decades that turned Antwerp into one of the most strongly defended cities in history.

I found out more about the wooden house in a little booklet published by Antwerp provincial heritage department – Houten villa’s en planken dorpen. Tijdelijk bouwen in het schootsveld rond Antwerpen (Wooden villas and timber villages. Temporary buildings in the firing line around Antwerp).

The Law on the Preparation for War of 1815 made it illegal to build within 585 metres of a military fortification. The aim was to remove anything that might help an enemy. The legislation led to anger after the government launched a plan in the 1860s to fortify Antwerp with a ring of eight massive forts. Homeowners and farmers were abruptly informed that their houses had to be torn down. Despite the protests, the government pressed ahead. More than 1,000 houses were destroyed, along with 156 farms and seven schools. It was a brutal policy enforced by the police and the army. In 1862, the government brought in 50 soldiers to prevent any trouble as a farmhouse was torn down.

But the law had a loophole. It permitted wooden buildings to be built, as long as they could be quickly demolished or set on fire, in the event of invasion. And so, hundreds of wooden houses were built on the empty land around the fortresses. Known in Dutch as servitutenwoningen (or easement houses), they ranged from modest terraced homes to impressive villas with ornate gables.

Beveren Fort Liefkenshoek in 1908

The owners probably thought they were safe. After all, Belgium was a neutral country. And Germany was more interested in crushing France. But the illusion of safety was shattered on August 4, 1914, when the German army crossed the border into Belgium. As the invading army approached the Antwerp forts, some 276 houses were torn down. Hundreds of trees were also chopped down around the forts. As a result, the area around Antwerp was described as looking like a battlefield before a single shot had been fired.

The easement law was abolished in 1924. Most of the wooden houses were eventually replaced by solid brick homes. But there are still 40 of these fragile timber houses dotted around the Antwerp area. Many are in the suburbs of Deurne and Kapellen. They are silent reminders of a massive project to protect Belgium’s second city.

Fortress Antwerp

The Antwerp suburbs are dotted with strange, unnoticed anomalies like the wooden houses. They reflect the city’s role over many centuries as a military stronghold. There are defensive walls that go back to the 16th century, fortresses designed to deter the armies of imperial Germany, ditches that were meant to stop Hitler’s tanks from reaching Antwerp.

These relics add up to one of the densest concentrations of military defences in Europe. Many have now been repurposed as nature reserves, tourist sites or sport venues. Some, like the wooden houses, are virtually forgotten.

The most impressive remains are seven giant fortresses built in the 1860s by the young Belgian military engineer Henri-Alexis Brialmont (an eighth fort was destroyed). Born in 1821 in Venlo (then part of Belgium, now a Dutch city), Brialmont planned to defend Belgium with rings of forts around the strategic cities of Antwerp, Liège and Namur. Brussels, under the plan, was an open city, with no defences at all.

Brialmont campaigned to persuade reluctant politicians to release the funds, some 40 million Belgian francs (about €385 million in current value). He was helped by King Leopold II who supported the project on the grounds that it would prove Belgium was a serious world power.

It was a massive undertaking that took four years and 14,000 workers to complete. The forts became proud symbols of Belgian ingenuity and independence. As they were being constructed, artists were sent to record the work. Several of the paintings now hang in the Military Museum in Brussels’ Cinquantenaire Park.

Under the plan, Antwerp was turned into a mighty fortress, the National Redoubt. If the country was attacked, the king, government and army would move to the safety of Antwerp, where they could hold out for as long as necessary.

Brialmont became a national hero. He was praised as Belgium’s Vauban, after the 17th-French engineer who built France’s ring of defensive fortresses. Brialmont is commemorated in Brussels by a statue that stands on a little square off Rue Royale, next to the parliament. He is shown holding a rolled-up military plan. Brialmont, it says on the plinth, 1821-1903. No further explanation. The country appears to have forgotten the general with the bold plan to save little Belgium.

One of Antwerp's 34 forts

Maybe just as well. The eight great forts soon became obsolete as artillery firepower increased. By the end of the 19th century, the brick-built structures offered no protection against the latest German guns. One glum soldier described the forts as not much better than cardboard.

But Brialmont stuck stubbornly to its plan. A new ring of 26 forts was constructed in the countryside around Antwerp, some 15km from the city. Built of reinforced concrete, they represented the very latest in military design. A 500-metre strip of land was cleared in front of the forts. Thousands of local people were moved from their homes in this enormous national security operation. The outer ring includes Fort Breendonk where the Nazis created a concentration camp in World War Two.

Brialmont never lived to see his plan put to the test. He would have been shocked to see how quickly the forts fell after the German army invaded in the summer of 1914. Within a few weeks, all the forts around Liège had surrendered. By August 17, fortress Antwerp became the de facto capital of Belgium. The king and queen moved into a baroque palace on the Meir. The parliament based itself in the opera house. And the war ministry moved with its maps and battle plans into the glittering Stadsfeestzaal.

Fort van Bornem

They thought they were safe behind Brialmont’s two rings of forts. But on August 25, the mood of confidence was shattered when a Zeppelin dropped bombs on Antwerp’s Stadswaag square, killing five people. The royal couple immediately sent their children to the safety of Britain. Meanwhile, the German army was attacking the outer ring of forts with the latest heavy artillery. The Belgian weaponry lacked the range to hit back.

By early October, several Brialmont forts in the outer ring had surrendered. The young Winston Churchill sailed to Antwerp to offer support. More than 2,000 British troops arrived in the city (poet Rupert Brooke would be stationed at Fort 4). An old photograph shows two London buses carrying the troops through the streets of Antwerp. But the Germans kept taking the forts, one at a time. On October 7, the king and queen finally fled from Antwerp. The Brialmont plan had failed spectacularly.

The battle of the Brialmont forts is hardly remembered these days. Not many people know of the heroic struggle to save the forts at Sint-Katelijne-Waver, Wavre and Lier. But it was one of the earliest victories for the German military machine. It showed the emergence of a brutal new form of warfare that Brialmont could never have anticipated when he launched his plan in the 1860s.

Brialmont in Budapest

Back in the 19th century, Brialmont’s strategy was widely admired. His military ideas eventually reached Bucharest, where King Carol I was looking for a way to defend his young country, formerly part of the Ottoman Empire. The Belgian engineer was invited to Romania several times to explain his principles to the war office. The king decided that his capital city, like Antwerp, had to be defended no matter what the cost. Brialmont was commissioned to design a ring of 18 massive forts around the capital, linked by a road and railway.

The work began in 1884. But it turned out to be a complex undertaking that took more than two decades to complete. Soon after the work was finished, the forts were declared obsolete. They could easily be attacked by aircraft or hit by long-range guns. When the German army invaded in 1916, the 18 forts had already been abandoned, and the city was taken without much of a fight.

Statue of Henri Alexis Brialmont in Brussels.

The forts around Bucharest are still standing. Some are still used by the army. Others are collapsing, overgrown with vegetation. None of them appears to be open to the public, although they are sometimes visited by urban explorers who post photos online showing flooded rooms, crumbling walls, piles of twisted metal. It might already be too late to save them. But if Romania is looking for inspiring ideas, it should look at the Antwerp forts.

Storming the forts

Buried in the landscape, the 33 surviving Brialmont forts are a forgotten episode in Belgian history. Many people don’t even know they exist. Eight forts are still used by the army. Some 17 belong to local municipalities. The others are privately owned. Many have become unexpected nature reserves in the Antwerp suburbs. There’s a disco in one fort. A summer café in another.

The best way to see the forts, I was told, is to follow the Brialmont cycle route. And so I set off one morning from Berchem station in Antwerp, following signs for the 44km route Herover de Forten (Storming the Forts). All but one of the eight original forts are still standing. The fort at Wijnegem was torn down in 1959. In its place, a modern shopping centre.

Fort 3 Borsbeek, Fortengordel, Antwerp

The cycle route crosses the busy Antwerp ring motorway. It follows the line of the massive wall that formed the first line of defence around the city. The wall has vanished, but there are still a few traces along the edge of the ring. The city is currently working on a plan to reconstruct a section of the defences under its Park Brialmont plan.

The route follows the ring for 3km before it hits the E34 motorway. Once across the heavy motorway traffic, the route follows quiet suburban streets. It passes Wijnegem shopping centre, site of Fort 1, then turns south to Wommelgem, Fort 2. The red brick building has been repurposed as a museum site with five specialised museums (normally closed). A colony of some 50 bats has also settled in the abandoned fort.

On to Fort 3, Borsbeek, buried in the trees near Antwerp Airport. The fort was damaged in both wars. It’s still a ruin, surrounded by a fence. But the urban explorer Ferdinand Xerbutri managed to crawl through a hole to get dramatic pictures of the interior. Some of the images he has posted online look like ancient Roman ruins.

Next stop, Mortsel, Fort 4. This is the most accessible of the fortresses (located close to Mortsel-Oude God railway station, open most days from 8am to 5pm). Bumping across a bridge, and through a gloomy tunnel, I ended up inside. You can walk around the moat, explore dank tunnels and climb up onto the roof. There’s a huge summer bar here in an abandoned hangar. Informative signs explain the fort’s history.

Fort Mortsel, Antwerp

You learn about the soldiers who manned these forts in the 19th century. They were recruited by lottery – pick a low number, and you were conscripted. But you could buy an exemption, so the recruits were mostly poor and often illiterate.

On to Fort 5, Edegem. I was beginning to recognise the elements of a Brialmont fort. The classic star structure, the moat crossed by a drawbridge, the iron gates. The formidable entrance with its hints of a mediaeval castle. And the dark tunnels that take you into the belly of the fortress.

A recent makeover has turned Edegem’s fort into a coworking space, fitness centre and art gallery. Known as BLWRK (short for bolwerk, or fort), the project has repurposed part of Brialmont’s military stronghold as a space used by tech startups, landscape architects and lawyers. I counted more than 20 firms based in the white vaulted interiors that were built to survive a heavy bombardment.

The workspaces have big windows that look out on the thick woods that have grown up over the years. It makes a unique workplace that is a short bike ride from Antwerp and yet feels like a long way from the city.

I pedalled on to Fort 6 in Wilrijk suburb. This one has been abandoned. Trees grow out of the roof. The walls are collapsing. It’s waiting for someone to come up with a plan.

I decided to cut short the tour here and head back to Berchem. By now I understood the logic of the forts, each one buried by trees that have grown up over the years. They are mysterious reminders of Belgium’s historic role as the battlefield of Europe.