How successful are European countries at unifying their populations linguistically? What part does the spread of English in Eastern Europe play in NATO’s hybrid war against Russia. These and many other questions about Europe’s rapid linguistic transformation can now be answered in a few clicks.

Philosopher Philippe Van Parijs reflects on current debates in Brussels, Belgium and Europe.

Europe’s linguistic landscape has not changed more dramatically – at least, without population displacement – than it has over the last three decades. This has been nothing short of a linguistic revolution, the full extent of which can be assessed thanks to an imaginative use of a 2024 Eurobarometer survey produced by the European Commission.

The official report and fact sheets cover the many aspects of the survey, but give little insight into the profound transformation of Europe’s language usage and its implications. Luckily, Languageknowledge.eu, an interactive website that mobilizes the Eurobarometer’s linguistic data, has just launched a new version to help make sense of what is happening.

The website provides information on the native language of residents in each of the European Union’s 27 Member States, as well as on the languages they learned later in life. It divides the survey participants into three age groups (15-34, 35-54 and 55+) and does so using both the 2024 Eurobarometer survey and its 2012 predecessor.

Linguistic nation-building

Using these data, the website can tell us, for example, which countries are most successful at national unification through the linguistic integration of both newcomers and regional minorities. Of the EU’s 27 Member States, 24 use a closely related word for their national language and their country. (Austria, Belgium and Cyprus are the only exceptions.) This homonymy is no accident. The unity and even the territorial integrity of a nation is closely linked to the sharing of a single language by all or most of its citizens.

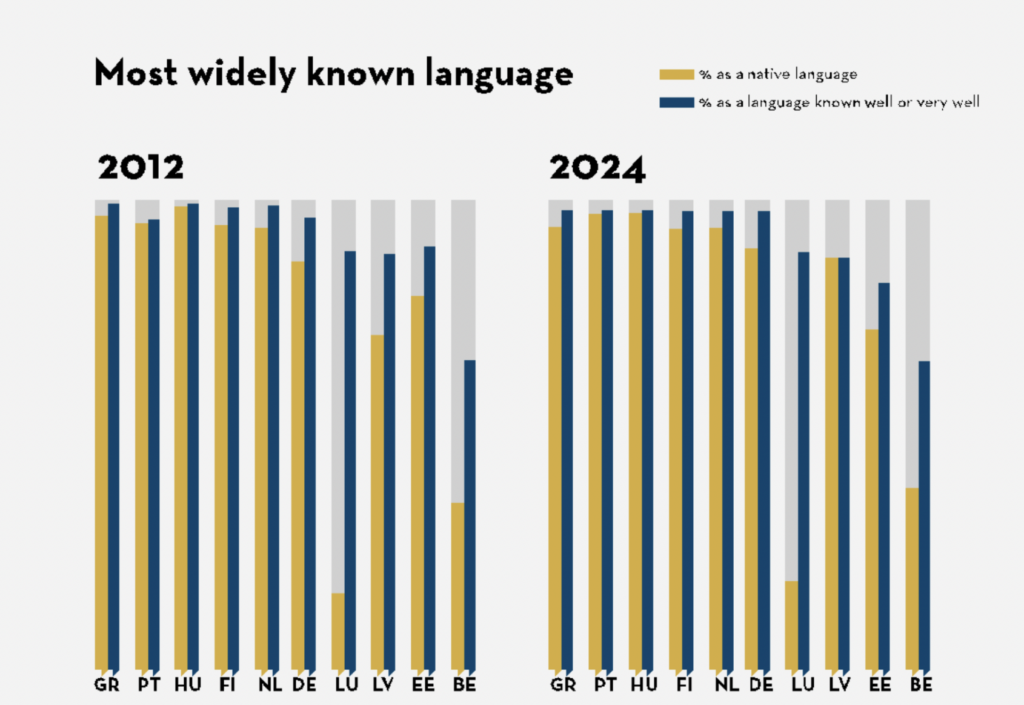

It turns out that nearly all EU Member States are less linguistically unified in 2024 than they were in 2012.

Six countries manage to get nearly 98% of their population to know their national language well or very well. That wasn’t too difficult for Hungary, which has the highest proportion of native speakers of the national language. It was, though, a major achievement for Germany, with less than 90% of native German speakers.

But what about the other end of the scale? The four least linguistically unified performers include Latvia at 88% and Estonia at 82%. Not so surprising, given that about a quarter of their populations is native Russian-speaking (compared to only 4% in Lithuania). The other two low performers are peculiar cases: Luxembourg with about 89% and — by far, the lowest — Belgium, with less than 66%.

More people in Belgium and Luxembourg can speak French than any other language. But French is not the main native language in either country (it’s Dutch in Belgium and Luxembourgish in Luxembourg). Nor is French the national language in Luxembourg – and it is only one of three national languages in Belgium.

Yet French was declared the only language of legislation in Belgium’s 1831 constitution when Luxembourg was still part of the country. Belgium scrapped this exclusivity in 1898; Luxembourg never did. This is arguably the main reason why French has remained far more of a shared language in Luxembourg than in Belgium, and why the national unity of Luxembourg is less contested than that of Belgium.

English first in Europe

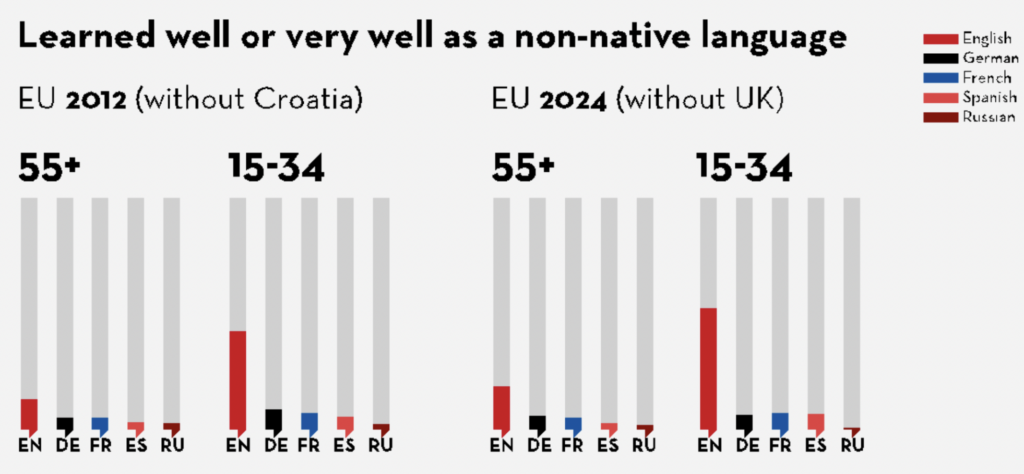

What about knowledge of foreign languages? This is where the breakdown into three age groups becomes particularly instructive. In the 2012 data for the EU, the top trio of English, German and French is the same in the oldest and the youngest age groups – but the percentage gap between English and the other two languages grew dramatically from the oldest to the youngest. This increase included, however, the impact of the sharp rise (from 4% to 16% of the British population) in the number of immigrants who learned English in the United Kingdom.

In the 2024 data (where Croatia has replaced the UK), the top trio is the same for the oldest age group. For the youngest age group, German has been overtaken by French and Spanish, despite Germany’s success, as noted above, in getting its migrant populations to learn German.

However, the most spectacular development is the further progress of English. Most Europeans in the youngest age group now claim to master it as a non-native language. Clearly, Brexit did not halt the march towards a common lingua franca.

Is this a blessing or a curse? Both. It’s a blessing to the extent that it facilitates communication and cooperation across the EU, and it’s a curse to the extent that it accelerates the brain drain from the EU to Anglophone countries.

Soon English first in Belgium too?

One surprising reflection of this quiet revolution is that there is one Member State in which a language without any official status is in the process of becoming the country’s most popular language. That is Belgium.

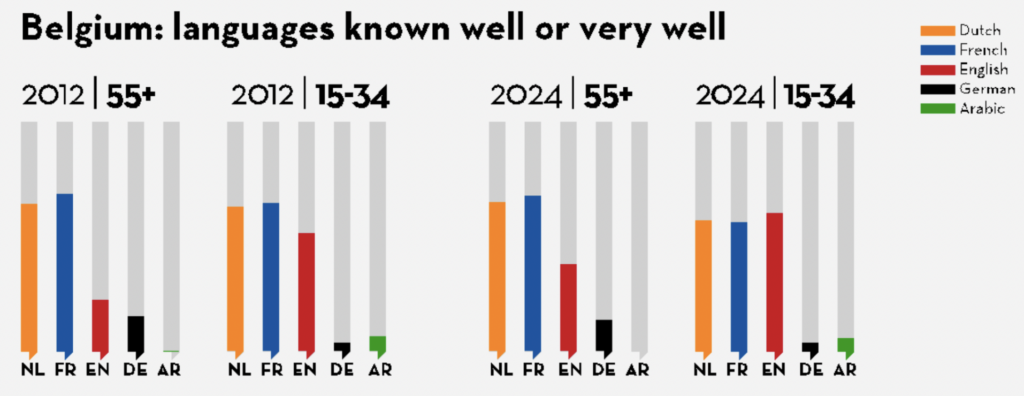

In all age groups in the 2012 data, and in all except the youngest one in the 2024 data, French is clearly the top language, followed by Dutch, English and German, Belgium’s third official language. But in the 2024 data, English comes on top in the youngest age group, while French is overtaken by Dutch, due to a decline in the learning of French in Flanders.

English is currently much less known in Belgium (49% of the total population) than in Sweden (76%) and the Netherlands (86%). Yet, among countries in which English is not an official language it is the linguistically divided Belgium, and not Sweden or the Netherlands, that can be forecast to be the first EU Member State where English will become the most widely known language.

This is already the case in the even more linguistically divided EU. According to the 2024 Eurobarometer data, more than 35.5% of the EU population claims to know English well or very well (only 2.5% as a native language), compared to 25% for German and 20% for French (mostly as a native language).

NATO-Russia language war

Whether in Belgium or at the EU level, the increasing dominance of English is not always welcomed – but it does not arouse the same passions as disputes over local languages in Spain, Belgium or the Balkans.

There is, however, one aspect of the rise of English that triggers higher emotions: the process, both top-down and bottom-up, by which English has replaced Russian in former Soviet republics and other eastern European countries.

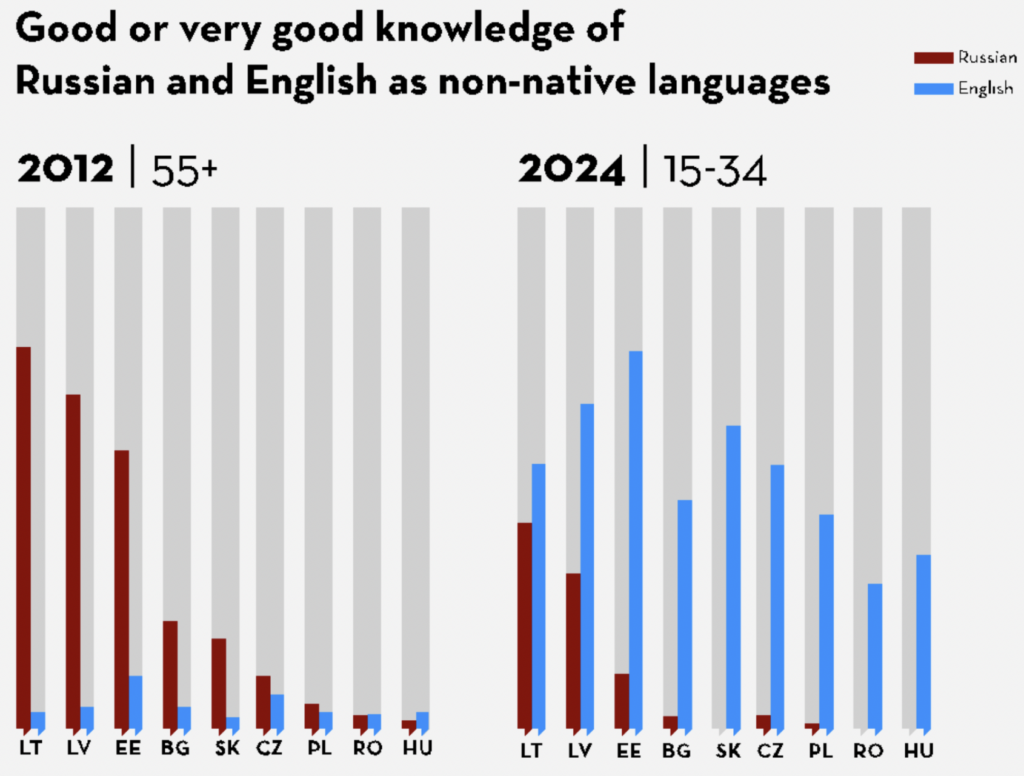

This is again best documented by comparing percentages in the oldest age group from the 2012 database (respondents aged 32 or more in 1989, when the Soviet Union started falling apart) and the youngest age group from the 2024 database (not yet born in 1989).

The table below shows that Russian learning varied widely between these nine countries, but also that it fell spectacularly in all of them, from the oldest to the youngest generation — and in three countries, all the way down to zero. This went hand in hand with a sharp rise in the knowledge of English, with a percentage over 10 times higher for the youngest than for the oldest generation in most of the countries.

While weapons draw borders, languages stabilise them. The nearly universal congruence between the names of European countries and the names of their languages reflects this reality.

Ukraine’s 2017 and 2019 laws that banned the use of Russian as a language of instruction and encouraged the use of English in all schools – and Russia’s symmetric policies in Crimea and the Donbas – illustrate that governments are fully aware of this.

Over the years, Moscow has griped about the expansion of NATO into countries that it considered part of its protective belt. It should have been more concerned about English replacing Russian as the main language channel of foreign information and influence in these countries. Eastern Europe’s language revolution is partly unintended, but it is nonetheless a major component in the NATO-Russia hybrid war.

These shifts show how language and politics are interrelated. The Commission has compiled easily comparable, illuminating and openly accessible figures that reveal deep societal changes. Now available in a user-friendly way, they can help feed better-informed public debates at both the national and EU levels.